On July 13, Jimmy Swaggart, a prominent Pentecostal televangelist of the 1980s, will be laid to rest in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, leaving behind a legacy of scandal. His ministry was marked by two prostitution-related incidents—first in 1988, when he tearfully confessed on television, and again in 1991, when he defiantly told his congregation, “The Lord told me it’s flat none of your business.” Swaggart’s denomination, the Assemblies of God, defrocked him, but his congregation proved to be remarkably forgiving. Although the televangelist’s work never reached its pre-1988 heights, Swaggart remained in the pulpit and on television until the day of his death at age 90.

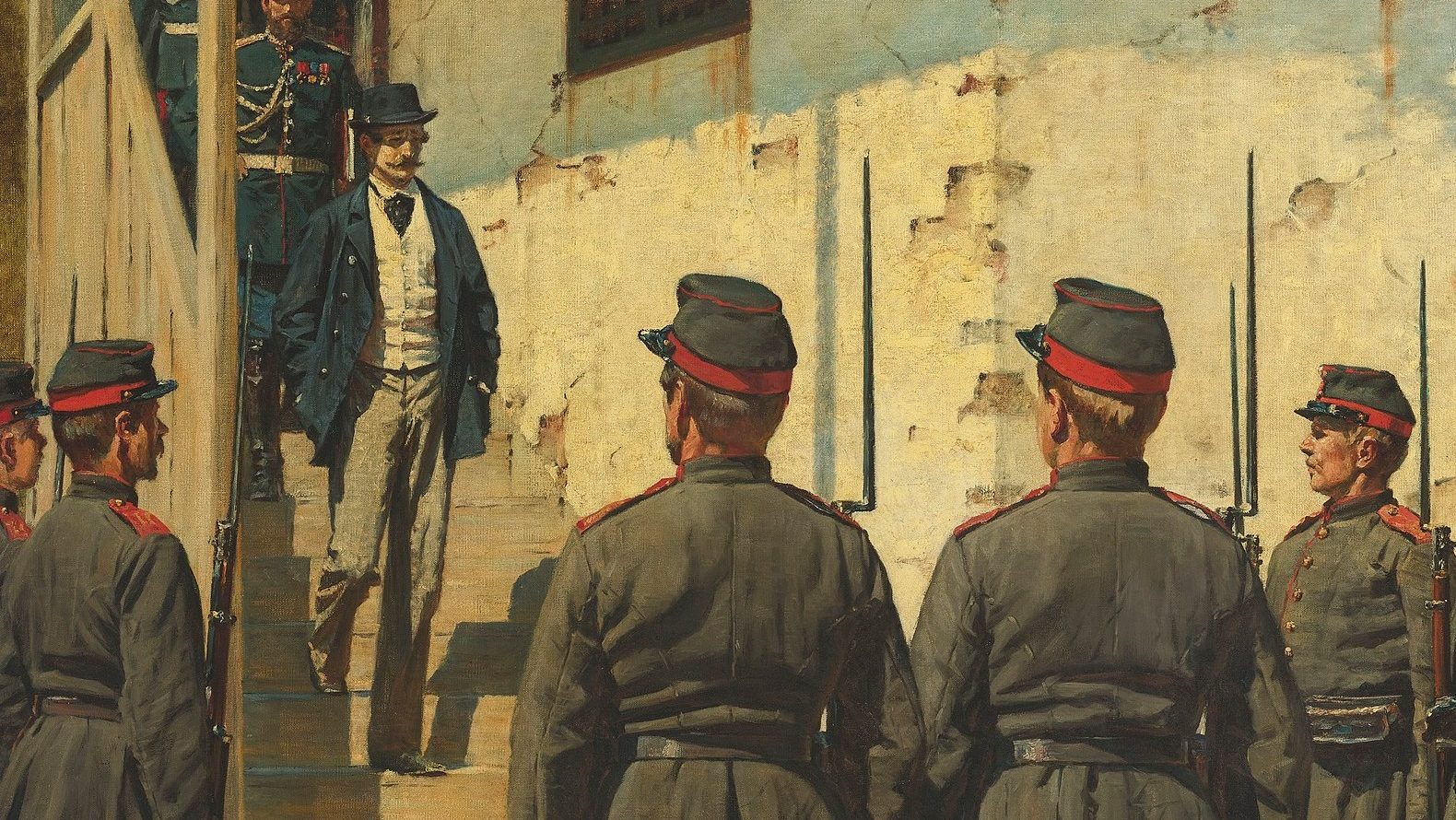

Swaggart’s sex life was big news, especially in televangelist circles. Other Christian TV stars of the ’80s and ’90s, like Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson, were using their media platforms to promote conservative political policies and rigorous personal standards of holiness when it came to human sexuality. But while Swaggart’s “fall from grace” was salacious, it was certainly not unique. He joined a long line of American celebrity preachers who lived and died (and then were often resuscitated) by the sword of American celebrity culture.

Swaggart’s distinct contribution to American Christianity and culture is interwoven with the legacy of his tight-knit Pentecostal family from Ferriday, a small Delta town in north-central Louisiana. In the 1950s, Ferriday would have seemed like an unlikely place to find figures who would shape mainstream American culture; the town was characterized by deep Pentecostal roots, entrenched poverty, limited educational access, and stark racial and economic divides that marginalized both working-class white people and African Americans.

Yet those seemingly inauspicious factors combined to change the trajectory of American popular culture when figures like Jimmy Swaggart’s cousin Jerry Lee Lewis brought the sights and sounds of Ferriday’s Pentecostal revivals to national audiences. Emerging from a wave of young Southern musicians in the 1950s, Jerry Lee embodied the ecstatic energy of Pentecostal and Holiness church services—both Black and white—and brought it to mainstream American airwaves.

Lewis and others introduced to the nation and then to the world a flamboyant performance style marked by driving rhythms, fervent vocals, and gyrating dance moves rooted in Southern Pentecostalism from places like Macon, Georgia; Tupelo, Mississippi; and Ferriday. As a son of Pentecostalism, Lewis caused a pop culture sensation—and quite a bit of public consternation—when he transformed the Pentecostal exclamation “great balls of fire,” used to describe encounters with the Holy Spirit from Acts 2 that led to the signature practice of speaking in tongues, into a provocative anthem with unmistakable sexual undertones.

Like Jerry Lee Lewis, Swaggart was an accomplished musician—but he was also among those who condemned rock as the “Devil’s music.” Conservative white Protestant critiques of rock-and-roll in the 1950s often reflected anti-Black racism, portraying the sounds of the genre, rooted in African American music forms like jazz and boogie-woogie, as especially distasteful, occult, and morally corrupting. And Pentecostals like Swaggart—both Black and white—were deeply frustrated that the sounds of their churches were used by “worldly” rock-and-rollers. Rock was, for them, a particular spiritual threat, mocking God and desecrating what was holy.

Jimmy Swaggart may have decried rock. But in the end, the same environment that helped birth the Devil’s music fostered the spiritual intensity, commercialism, celebrity, and populist appeal that would later define his Pentecostal preaching.

Like the equally infamous Assemblies of God televangelists Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker, Swaggart commodified Pentecostal culture by packaging its emotional fervor, miracle narratives, and apocalyptic urgency into polished, watchable television. As Christian television expanded globally, Swaggart translated the ecstatic worship of backwoods Southern revival tents into a mass-media empire that reached millions. His broadcasts featured fiery sermons, gospel music, altar calls, and plenty of opportunities to purchase merchandise.

In this way, both Swaggart and Lewis helped turn a once-marginal religious tradition into one of the largest, fastest-growing forms of Christianity in the United States and beyond. In fact, recent research funded by the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) reveals that charismatic and Pentecostal Christianity is rapidly growing within the population of self-identified “born-again” or evangelical Christians, reshaping both the religious and the political landscape in the US.

Historically marginalized by evangelical leaders, charismatic practices that Swaggart promoted, such as speaking in tongues, prophecy, and divine healing, have gained broad acceptance, especially among younger generations. Gen Z and millennial Christians are more likely to attend charismatic or Pentecostal services, which suggests that the future of evangelicalism may be increasingly charismatic. As traditional evangelical denominations decline and nondenominational charismatic congregations ascend, the rise of charismatic Christianity may increasingly shape the future of Christian conservative activism in America.

Like Swaggart’s congregation in Louisiana, some charismatics and Pentecostals have shown a high tolerance for disgrace. Assemblies of God, the denomination that defrocked Swaggart, is now the denomination most supportive of President Donald Trump, a man with his own lengthy history of defying the traditional moral claims of conservative white Protestantism. In charismatic church circles, Swaggart’s return to Christian ministry after public embarrassment has been imitated by celebrity preachers like Ted Haggard, Carl Lentz, and many others who endure public embarrassment and find their way back to the spotlight, albeit often in diminished fashion.

Eventually, in spite of critiques from church gatekeepers, Pentecostals and charismatics found a way to create rock music that conservative white Protestants could enjoy and endorse. Evangelical media makers turned that music into a profitable market niche known as contemporary Christian music, which became the soundtrack for evangelical activism in the late 20th century. Through their knack for utilizing the power of media and the marketplace, Pentecostal and charismatic musicians now create a significant portion of new church music in America.

The story of Jimmy Swaggart, then, is not only the story of one famous Christian leader’s lasciviousness. It is also the story of how celebrity culture and mass media are shaping the American evangelical landscape. If evangelical voters had been of the Moral Majority ilk, for instance, Trump’s political career probably would have been quite short. But for communities shaped by Swaggart’s legacy, scandal does not have to be an end. It can also be a beginning.

Leah Payne is professor of American religious history at Portland Seminary and an affiliated scholar at the Public Religion Research Institute, as well as host of the podcast

Spirit and Power: Charismatics and Politics in American Life. Her book, God Gave Rock & Roll to You: A History of Contemporary Christian Music, won Christianity Today’s 2024 book award for history and biography.