One autumn morning in 2016, during a season shot through with loneliness, I learned that my family and I lived only a 10-minute drive from the Bonhoeffer-Haus, the memorialized home of Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

We had just moved from the Washington, DC, area to Berlin for my husband’s work, spending those summer months awkwardly trying to settle ourselves in a new country. I was homesick, but not just for home—for another time altogether. From across the Atlantic, I was disillusioned by the rancorous partisan discourse unfolding in American public life and felt especially grieved that there was coarse disrespect even among those who claimed to follow Jesus. These ruptures left me feeling raw, alone, and fearful.

A visit to Bonhoeffer’s house would do us good, I figured. He was a hero lauded for the faith and theology that animated his opposition to Nazism—a Christian good guy in a time of Nazi bad guys. We could be inspired, I thought, hopeful again that maybe good people like him would rise to the occasion in our present messy world.

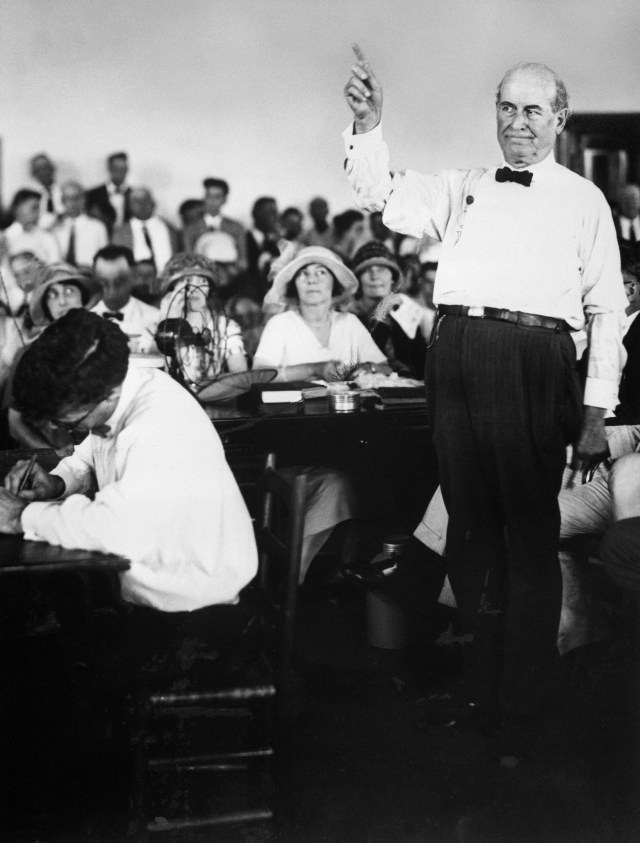

So we packed our three kids into the car for the house’s Saturday morning English-language tour. Upon arrival, I took in the black-and-white photographs hanging on the walls of the conference room where we gathered. Some were of Bonhoeffer. A few, like those of Karl Barth, were familiar—but most of the images featured people I didn’t know at all. Sometime during the guide’s talk, in that room full of strangers’ photographs, I realized I was not getting the story I’d expected or even wanted to hear.

Rather than training a bright spotlight on the lone hero Dietrich, the guide gave a careful historical overview of the house and the many people connected to it. The context was harder to follow than my good-guy-versus-bad-guys framing and demanded a different form of attention than I expected. It involved a wider group of characters, dates, places, and complicating elements about the Confessing Church (which rose in opposition to the pro-Nazi German Protestant church) and about Bonhoeffer’s role in a 1944 military conspiracy—far more nuanced than the American retellings I had previously encountered.

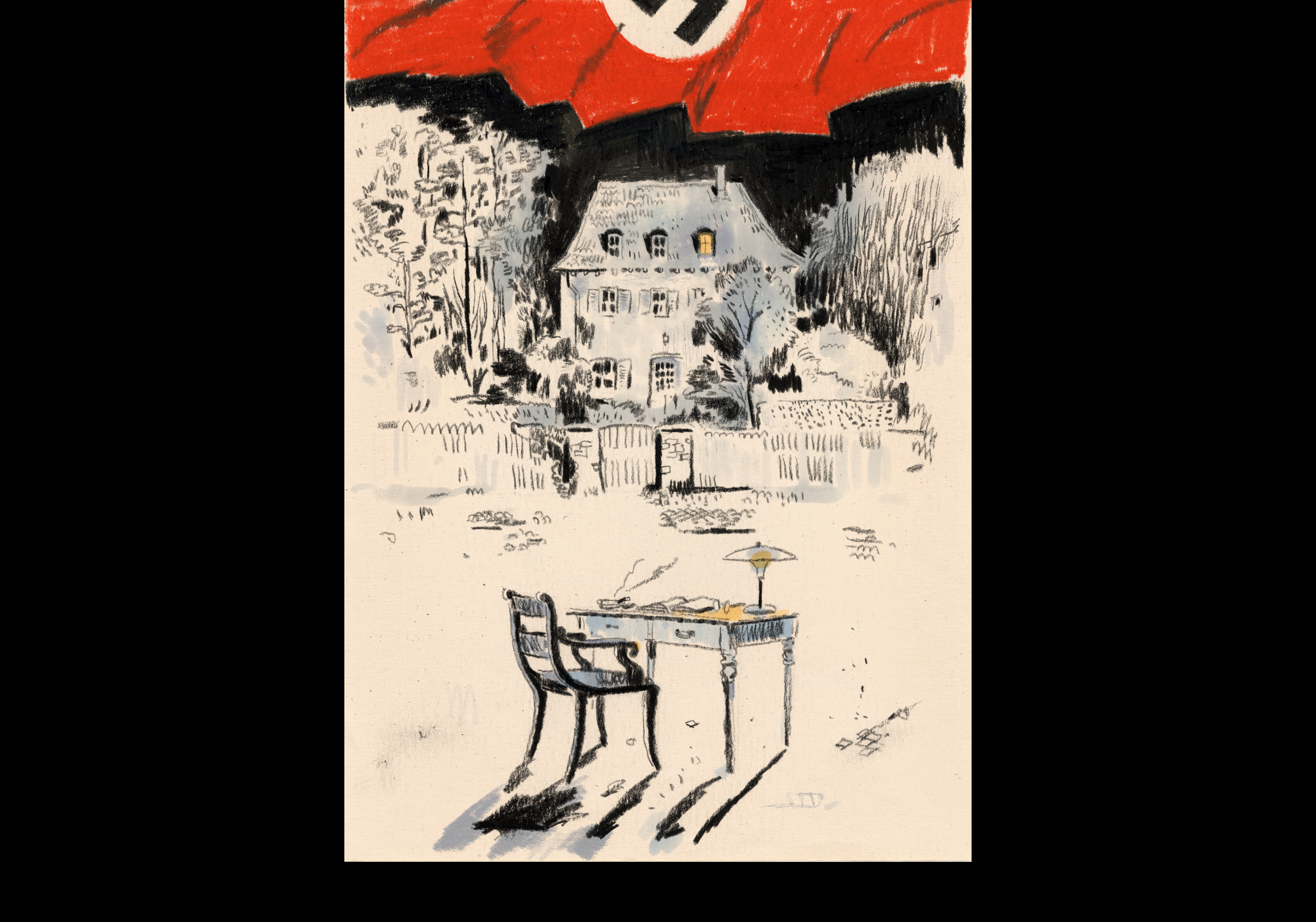

At the end of the talk, the guide invited us to visit Bonhoeffer’s upstairs bedroom, ringed with bookshelves, and to sit at his desk, with its signature teal lamp and a small cigarette burn on the matching velvet blotter. It was in that room that the Gestapo arrested him in 1943; he was executed two years later at the age of 39 in the Flossenbürg concentration camp.

I too was 39 that morning in his room, and I found my attention turning to a tangle of existential questions. What would I have done? Was I doing anything significant now with my life like he did? What had I really wanted from this tour of Bonhoeffer’s house?

Following that first visit, I scheduled another tour for myself, and then another, intrigued and terrified by the silent witness of that ordinary house. It held the mingled memories of joyful family times and gatherings with neighbors but also conspiratorial conversations and jagged emotions of fear, anxiety, and immense grief. Behind its doors was a world of people—a few recognized, many now forgotten—who struggled to make sense of the time and its demands as best they could.

Rather than being superhuman, as I had secretly hoped, the Bonhoeffers and their friends were ordinary people who had no desire to be heroes, much less Christian ones. They were an elite Prussian family with a strong sense of civic obligation, prizing sound thinking and moral courage at a time when such things were in scant and diminishing supply.

From my historical vantage point, the house and its people appeared disadvantaged against the noisy bombast of the Nazis and the social pressure to comply. Yet the Bonhoeffers and their friends still sought to live responsibly, decently, and faithfully. That witness terrified me but also compelled me to learn more. As I listened, their lives issued a quiet, persistent call—not to their world but to my own.

After making more visits over the next six months, I became a volunteer guide myself, warmly issued a key for the door as if I were a trusted neighbor. But nearly nine years since that first visit, as Bonhoeffer’s story continues to be cited, celebrated, and sometimes misconstrued by the American church, we need to ask ourselves: What are we doing with Bonhoeffer, and why?

“Laura! The bed is IKEA!”

The comment, typed in the margin of my book draft, made me laugh and cringe. As painful as it was, I had grown accustomed to having my romanticized notions about Bonhoeffer punctured by Gottfried Brezger, a retired pastor and longtime Haus guide.

My two years as a guide had grown into a book, in which I distilled lessons I learned from my time at Bonhoeffer’s house. The memoir was in its infant stages then, and Brezger was direct in his feedback, repeatedly melting away my propensity to wax imaginative. In the case of the bed, I had written with pathos about the objects in Bonhoeffer’s room—his books, his desk, his clavichord—and then added some treacly foolishness about “the human-sized bed that once held a sleeping moral giant.” Nonsense. The desk was Bonhoeffer’s, Brezger averred, but the bed was a Hemnes.

Par for the course. In my interactions with Brezger, I routinely experienced the difference between my American and his German view of Bonhoeffer. I veered toward a mythologized picture of the man, while Brezger saw him firmly embedded in the rich fabric of history.

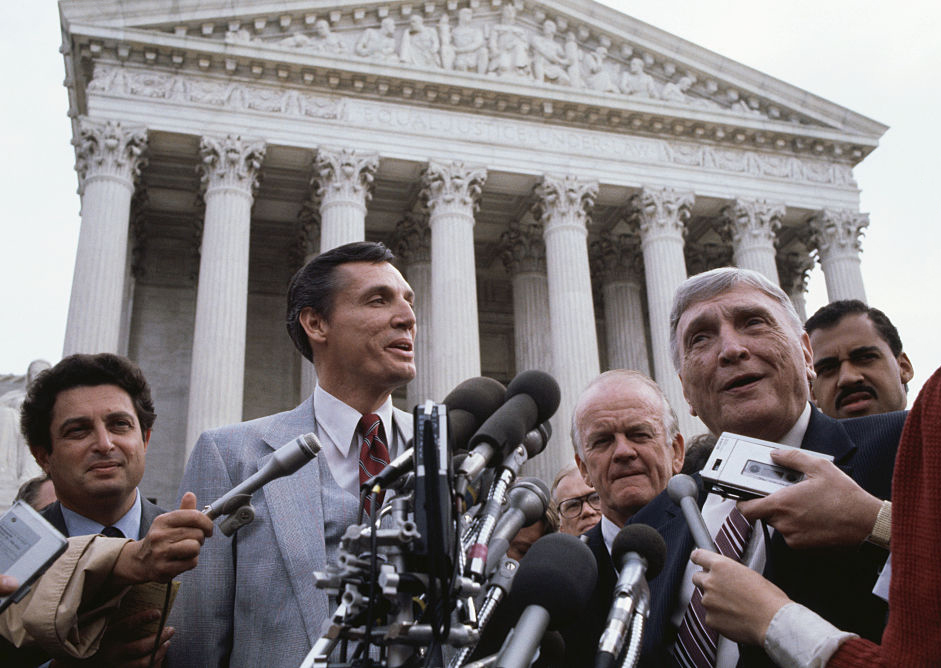

Our interpretations and interactions mirror our larger cultures. In the aftermath of World War II, American Christians hungered for stories of moral heroes and exemplary Christians. That appetite was first satisfied in the eulogies that theologian Reinhold Niebuhr and bishop George Bell gave of Bonhoeffer shortly after his death (even if his theology and prison writings later complicated the picture they initially painted).

More recently, Americans have repeatedly encountered the phrase “Bonhoeffer moment,” which fashions an abstract ethical principle out of the actual person. The phrase has come to mean that a tipping point has been reached in society and that violent action is now permissible. But those who use it this way fail to understand that Bonhoeffer never claimed his decision to support the plotters was morally justified or insisted others were ethically bound to follow him in it. Invoking his name and image like this may be an effective marketing technique, but it is not a serious engagement with his life or times.

I’ve observed Germans show respect for Bonhoeffer, but it is always tempered with caution toward any thinking that revolves too much around a charismatic figure, which is understandable given their country’s history with the Führer. Unlike in the United States, Bonhoeffer isn’t treated as a brand name or a celebrity. Instead, he is honored for the complex humanity of his life: for being a brilliant, evocative thinker and writer who lived life fully, intensely, and creatively, even in prison. As one of my former Bonhoeffer-Haus colleagues noted, some in Germany even refer to him as “the man with the song”; his beloved poem “By Gentle Powers” (“Von guten Mächten”) has been set to music by a variety of composers. But this creative, joyful person is rarely the Bonhoeffer we in the US hear about.

During my time as a guide, it was important for my American imagination as much as my Christian one to reframe how I told Bonhoeffer’s story. My fellow volunteers’ personally distinct tours were helpful in this respect, presenting a fuller picture of life in that era.

Martin focused on the house itself, pointing out that its location at the end of a dead-end street was more secluded and thus perfect for conspiring. He also explained recent historiography about women in the Confessing Church movement and Nazi resistance, including those largely forgotten, such as Elisabeth Schmitz and Gertrud Staewen.

High school teacher Martina drilled deep into the history of former students who died in Nazi resistance efforts—students who once attended the school where she herself teaches.

Other guides, like Brezger, concentrated on Bonhoeffer’s theology and its continued relevance. To this day, all of the guides invite visitors into conversation about these and other subjects, careful not to tend to a cult of Bonhoeffer but to remember him and others in their historical context.

While learning from these volunteers, I had to shed my desire—in my guiding and writing—to tell a merely inspiring story about his life that might satisfy visitors’ or readers’ appetites. Mimicking my fellow guides, I reminded people that his upstairs bedroom was often blue with cigarette smoke.

While giving a tour one day, I found myself flooded with pity and compassion for Bonhoeffer: Despite his intellectual gifts and credentials, he had a potholed timeline of halting life experiences. As the only adult Bonhoeffer child who still had a room upstairs, he leaned on his parents financially. Even when he lived elsewhere, he mailed his dirty laundry home to be washed, biographer Charles Marsh notes. At times, during my guiding years, I wondered whether I would have even liked Bonhoeffer if I had met him.

But these insights were a severe mercy for me and for him. I was starting to see that God loves and is served by real human beings: faulty, frail, fearful, and dependent, infinitely more varied than the successful leaders I was tempted to look to and lift up.

Increasingly, I came to see that my tangled emotional attachments to Bonhoeffer’s narrative were fed, in part, by restlessness in my own life. I was complicit in a larger Christian culture that cultivates a sincere but problematic, even sentimental, attachment to him—and to other Christian celebrity figures—as a kind of holy warrior. Their humanity cannot stand under the weight of deification we are tempted to load upon them.

The Bonhoeffer I’d wanted to hear about was an idealized figure who led a resistance movement with clarity and self-confidence, a bold operator in a bewildering world who I could follow in the dark. My neighbor Bonhoeffer, however, was as human as I was.

The danger of sentimentalizing our heroes is that such mythmaking can be exploited for our own ends. We cannot afford to be naïve about this. Portraying Bonhoeffer as an assassin, with a gun clutched in his hand, fails to demonstrate even a basic understanding of his life or thought. In a culture primed for violence through contemptuous polarization and radicalizing isolation, the temptation lurks to invoke Bonhoeffer’s name as justification for the moral worthiness of one’s cause and tactics, no matter how different they may be from his own.

This kind of causal instrumentalization hurts real people, including his living relatives. Tobias Korenke, a great-nephew of Bonhoeffer, told me by email that he and his family have been “deeply hurt by the abuse committed against Dietrich” for nationalist ends and political purposes—causes that Bonhoeffer would not have supported and against which he issued strong dissent.

But I came to realize that it’s not only Bonhoeffer’s life we sentimentalize. It’s also the Confessing Church he was a part of. To understand this better, I turned to my mentor Victoria Barnett, one of the general editors of the 17-volume works of Bonhoeffer in English and a theologically trained historian specializing in the German Confessing Church movement.

In the 1980s, Barnett conducted 60 interviews with surviving Confessing Church members, including Bonhoeffer’s sister-in-law, Emmi Delbruck Bonhoeffer. Her husband, Klaus, was one of Dietrich’s older brothers and was executed by the Nazis for his role in the 1944 military conspiracy, along with Dietrich’s brothers-in-law Hans von Dohnanyi and Rüdiger Schleicher. In her book For the Soul of the People, Barnett’s interviews unveil the depth of moral murkiness and the complicated circumstances that individuals in the Confessing Church faced.

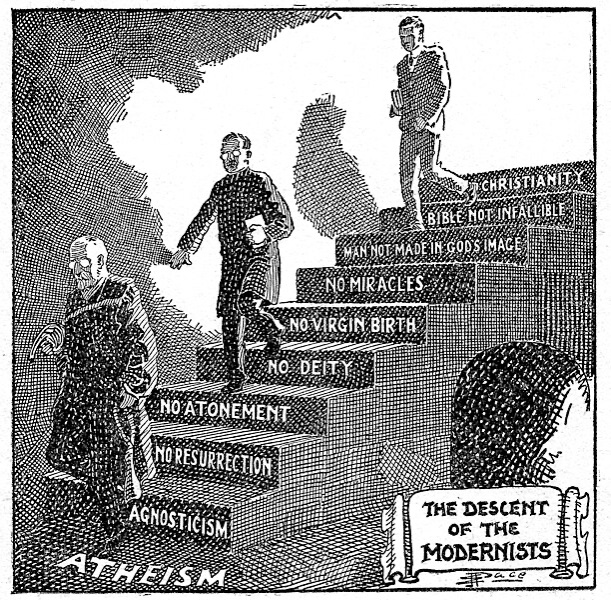

Barnett also points out that the German Confessing Church cannot be understood as a resistance organization to the Nazis. The Confessing Church emerged in opposition to attempts by the Deutsche Christen, or German Christians, to Nazify the church. But as a movement, it sought primarily to preserve the church, not to resist or overthrow the Nazis. In fact, some in the Confessing Church were even members of Hitler’s party.

Here and there, a few individuals in the Confessing Church sought to help those who found themselves crushed by Nazi propaganda and increasing levels of state-sanctioned terror aimed at genocide. But in terms of offering resistance, I realized I was not free to imagine the movement as one that primarily helped Jews or other persecuted groups. As Barnett said to me recently, “The Confessing Church’s leadership record is pretty poor in that regard.”

German society writ large hardly fared better. There was no national effort to resist National Socialism—only individuals and small groups from various sectors: artists and intellectuals, the workers movement and labor unions, and individual Christians. To varying degrees, as the German Resistance Memorial Center puts it, each of these “made use of what freedom of action they had” in defiance of the Nazi regime.

Amid the tensions of myth and history, there remains the man. As Barnett writes in The Christian Century, Bonhoeffer was “one decent human being who understood better than any of us that in evil times, we must remain faithful—if only for the sake of future generations.”

That is the harder task for us all. It is easier to turn to mythologized heroes than to begin to follow in their uneven steps of obedience to Christ. It is easier to write off faithfulness as extraordinary than to shoulder responsibility for our times. It is easier to let someone else speak up for our suffering and fearful neighbors than to do it ourselves.

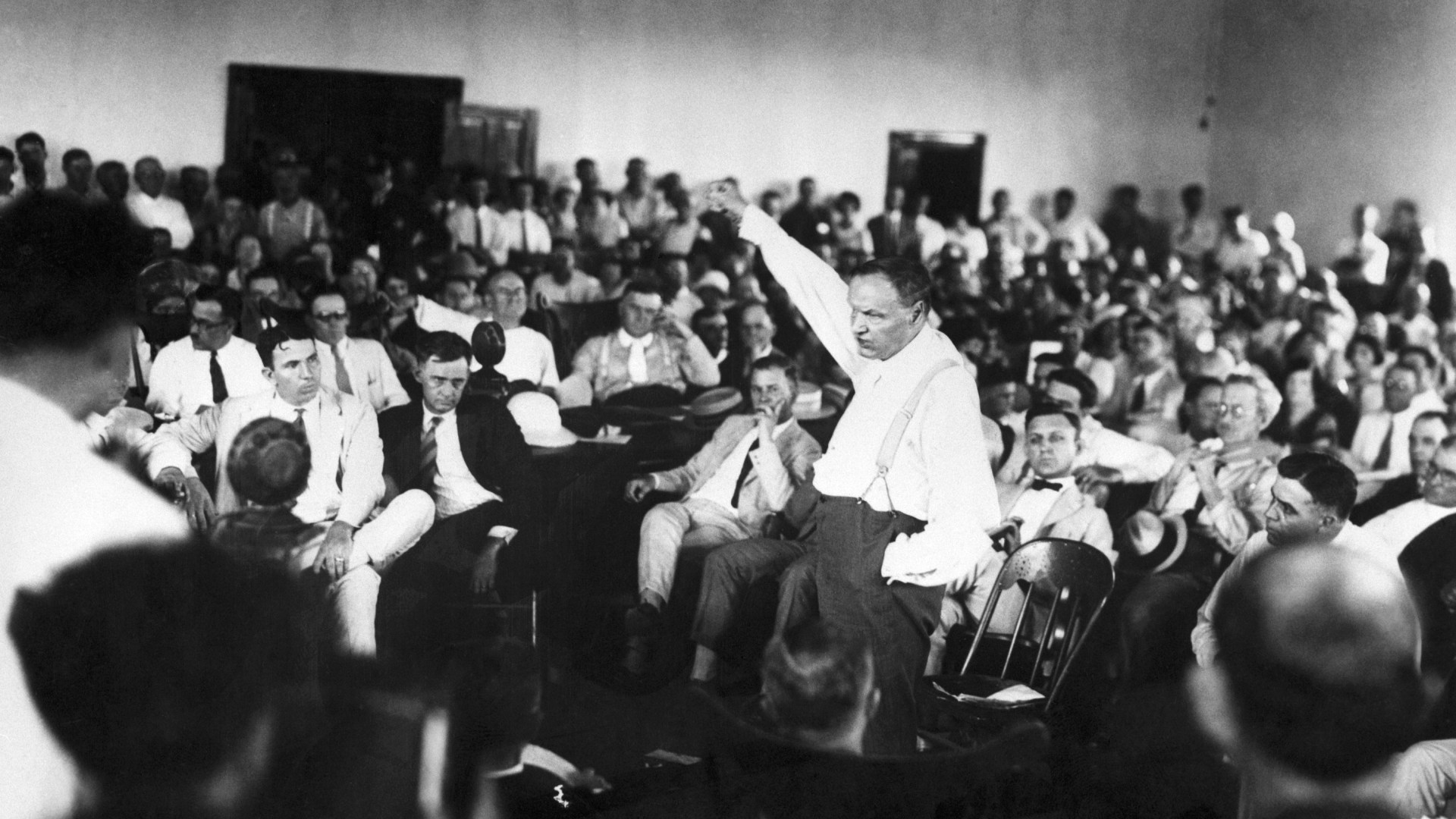

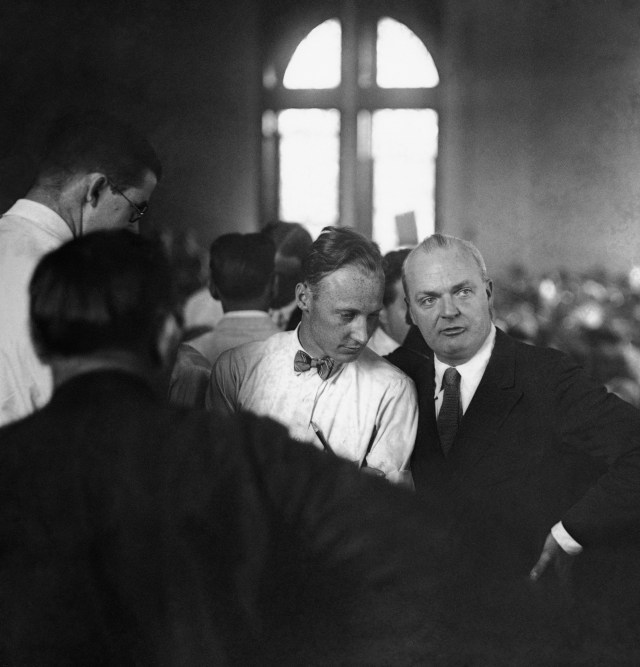

WikiMedia Commons

WikiMedia CommonsWhether in my pocket or my purse, the key to the Bonhoeffer family’s house jangled next to my own keys during those Berlin days.

My efforts to master the basic facts of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s life—as critical as these were—gave way to the gift of seeing him as a fellow human being. He was no longer a lone superhero but a member of a family, inextricably bound within larger communities and relationships.

To better see Bonhoeffer, I had to learn the names of the other people in the photographs on the wall. And I did this not by myself but with Brezger and Barnett, Martin and Martina, and all those who tended to the loving task of remembrance at the Bonhoeffer-Haus. To this day, I am still learning new names from that era.

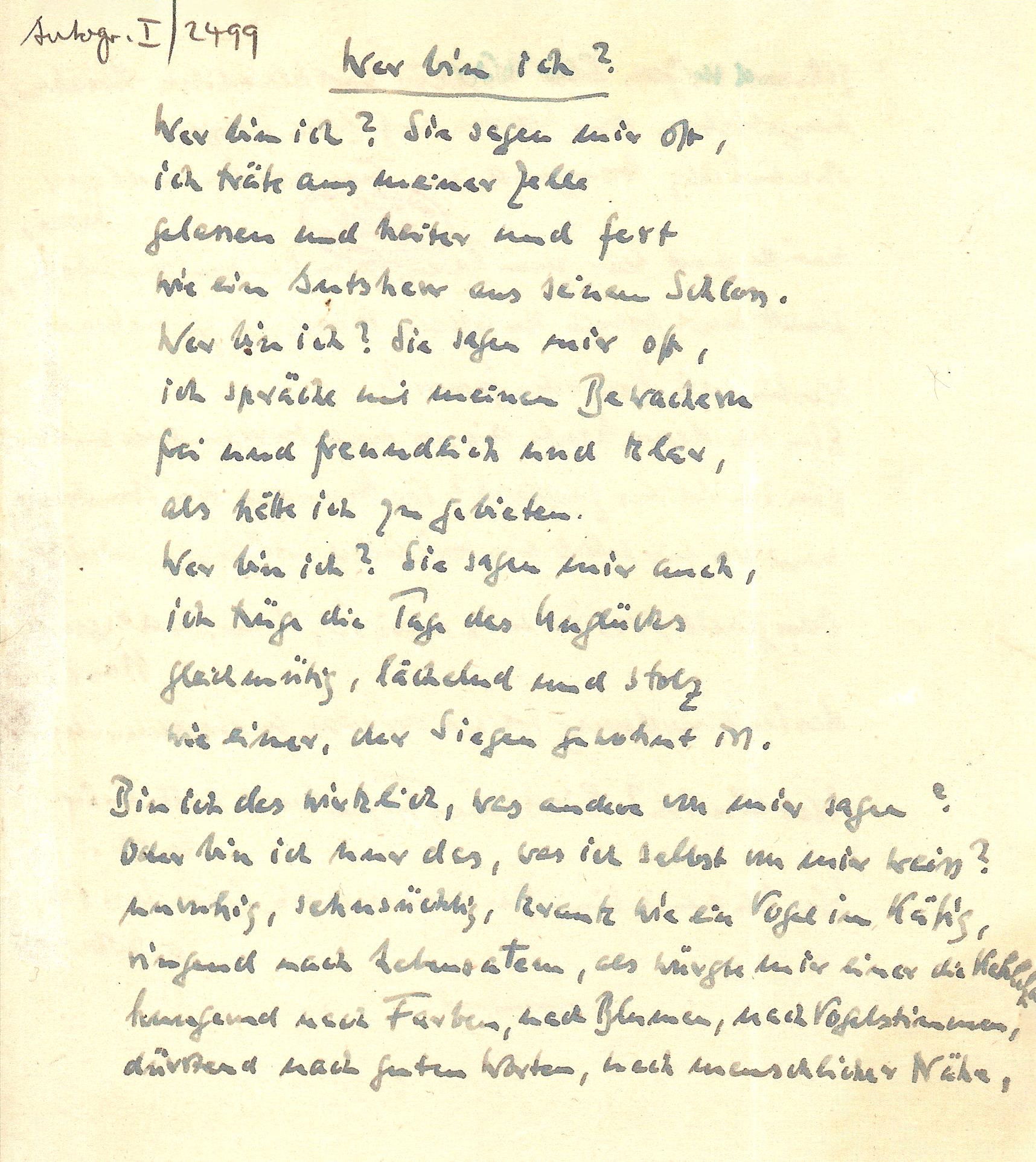

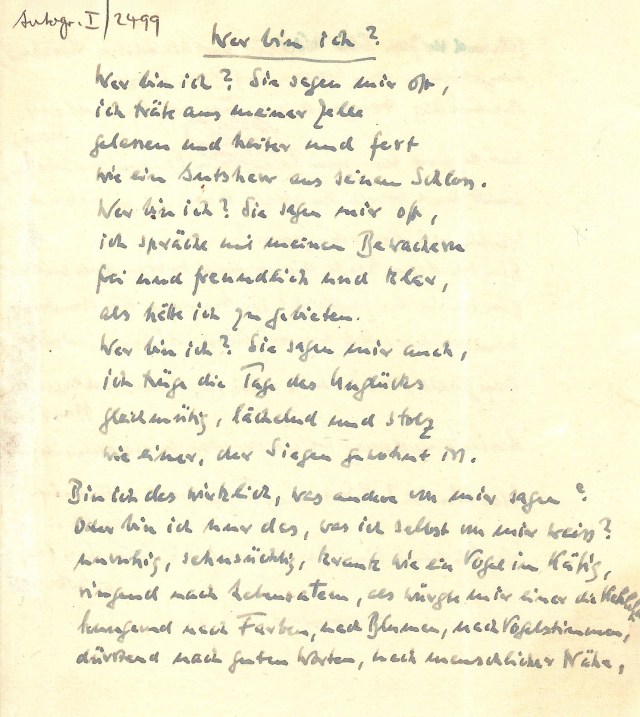

During his time in prison, Bonhoeffer wrote a poem that peels back the mythical man’s mask to show the genuine human, trembling at the questions, fears, and longings within himself. In “Who Am I?” we see him struggle to know how to answer:

Am I really what others say of me?

Or am I only what I know of myself?

Restless, yearning, sick, like a caged bird …

starving for colors, for flowers, for birdsong,

thirsting for kind words, human closeness,

shaking with rage at power lust and pettiest insult,

tossed about, waiting for great things to happen,

helplessly fearing for friends so far away,

too tired and empty to pray, to think, to work,

weary and ready to take my leave of it all? …Who am I? They mock me, these lonely questions of mine.

Whoever I am, thou knowest me; O God, I am thine!

This human Bonhoeffer remains an important figure of respect—not because he was perfect in his thoughts or actions or because he was singularly heroic, but precisely because he was not. He was on the losing side of the war, geographically, in a movement that also lost. But all the while, he dared to do the good, to keep wrestling for the gift of ordinary human life even as his world seemed bent on reveling in gross indifference and inhumanity.

As fear and complicity grew and morally preferable options narrowed, he continued to press into the bewildering pain of life’s questions before God. He was careful not to insist that others imitate him on the path he felt responsible to take. The arc of his life witnesses to the costly reality that even in failure, “God can and will let good come out of everything,” as he wrote in 1942. His life can nourish future generations’ moral imagining. In that respect, I think it is right to call him a saint—living history evidence of what God can do in a person’s life.

Bonhoeffer’s poetic questions might also illuminate traces of answers to life’s questions for us. They certainly gestured toward my own trembling questions on that first visit in 2016. To find the answers, I needed a sheltering place and hearts capable of housing my uncertainties and doubts. I found both at the Bonhoeffer-Haus, where slowly, answers began to emerge, tuned to my own life.

These answers touched on the basics of civic housekeeping as well as wholehearted obedience to Jesus: Feed the hungry; house the homeless. Give fellowship to the lonely and justice to the disposed, for, in Bonhoeffer’s words, “what is nearest to God is precisely the need of one’s neighbor.”

Knowing this, seek reconciliation with someone from whom you have grown alienated. Pray for a real enemy to the risen Christ who calls us to love, and use the Psalms to help you do it. Look at the lilies, listen for the voices of birds, and consider—as Jesus said we should.

Muddled desires, fear, anxiety, and myth-based emotional attachments had sent me to search mindlessly for a great man of history, a hero of the Christian faith at a time when heroes were nearly absent.

I did not find what I was looking for at the Bonhoeffer-Haus. What I found instead was a human being among other human beings—a man who, above all, belonged to God. And that remains, even now, a good and difficult gift.

Laura M. Fabrycky is the author of Keys to Bonhoeffer’s Haus: Exploring the World and Wisdom of Dietrich Bonhoeffer.