In this series

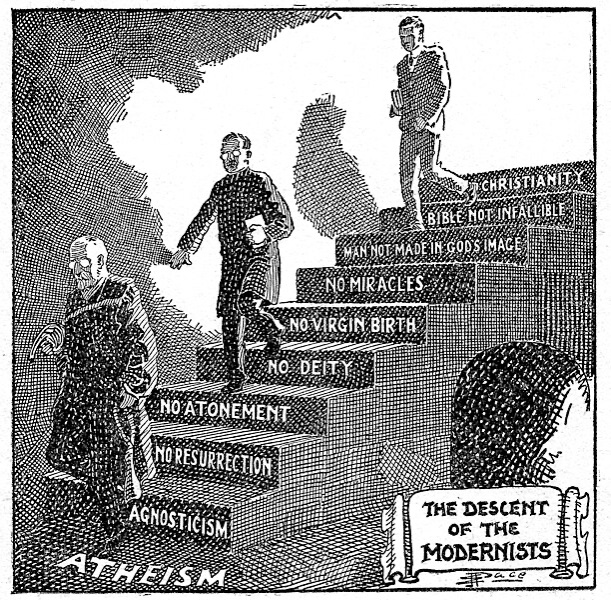

On its face, the term obsolete can sound like an insult. We apply it to technologies, ideas, and institutions that fall out of fashion, often with a mocking air (“Okay, boomer”) or a snarl of disgust (“Good riddance”).

Christian Smith means nothing pejorative with the title of his latest book, Why Religion Went Obsolete: The Demise of Traditional Faith in America. Popular ridicule of religious belief (and believers) certainly factors into the story he tells. But Smith, a distinguished sociologist best known for studying spirituality among teenagers and young adults, has more in mind than atheist attacks and secular sneers.

Why Religion Went Obsolete looks for explanations beneath recent portraits of religious decline. Why have rates of belief and affiliation plummeted among younger Americans? Smith’s answer lies in the development, over decades, of a “Millennial zeitgeist,” his term for the fierce cultural winds whipped up by a perfect storm of social, technological, economic, and political disruptions, all compounded by the failures and misdeeds of religious leaders and organizations. Even if those winds are weakening, Smith suggests, they’ve succeeded in conditioning younger generations to view religion the way digital natives might view a landline phone.

As Smith stresses, obsolete isn’t a synonym for theologically untrue or morally harmful. “Something becomes obsolete,” he observes more prosaically, “when most people feel it is no longer useful or needed because something else has superseded it in function, efficiency, value, or interest.” People don’t relinquish older phones in a rush of hatred or condemnation. They do so because peer groups, product lines, and communications networks nudge them toward the newer model. They flow with the cultural tide.

Smith sees similar patterns playing out among millennials and Gen Zers who reject religion. Yes, some leave in anger. Plenty can cite intellectual and moral objections. But most, perhaps, simply gravitate toward worldviews, lifestyles, and communities that better align with their cultural assumptions.

Because the book reaches into so many subjects and scholarly fields, CT invited three reviewers to assess it from different angles: a political scientist (to weigh its social science claims), a theologian (to reflect on the underlying cultural currents), and a youth ministry expert (to consider the church’s next moves). This symposium, as we’re calling it, closes with Smith’s own response to the reviews. We hope the entire package inspires fresh thoughts, fruitful debates, and fervent prayers for all who brave cultural headwinds to make disciples.

Matt Reynolds, CT senior books editor