As our twin boys played with their little sister across the classroom, they did not know what we knew: that this admissions interview could help set the course not only for their formative years but for life. Their future first-grade teacher asked why we wanted to enroll our children at her school.

Well, we said, so many reasons. Some are prosaic: The campus is one walkable mile from our house, and the schedule is convenient. Others are about pedagogy: Younger grades get up to four recesses a day, and there is no homework until middle school. Then there’s the classical education they’ll receive: Our children will study Latin and Greek. They’ll read the great works of literature I self-assigned in high school and college in a belated scramble to learn the cultural canon all my favorite writers seemed to know.

We didn’t bother to mention that we are interested because it is a Christian school. We didn’t bother because of course that’s part of it. We knew it; the teacher knew it; our boys knew it. Mentioning it would’ve felt like telling a real estate agent, “We’re interested in this property because the house has walls.” We want our children to have a deliberately Christian education because in school they will learn more than math and reading. They will learn about who they are and what God expects of them.

It’s not of course for everyone, I realize, including many faithful Christian families who choose public school or homeschooling out of a sense of calling or simply because there’s no other good option. For us, though, this choice is in some ways very simple. Of course we’re enrolling because it’s a Christian school.

But the project of Christian education in America is not as simple as that. It’s a project that, in much of the country in the fairly recent past, was wrapped up in rank and shameless racism defended by my fellow white evangelicals on biblical grounds.

As journalist Paul F. Parsons wrote in a CT cover story in 1987, there was “a widespread perception that [evangelical] Christian schools are racist. After all, what once was a Southern phenomenon of the 1960s—segregationist academies quickly formed in the name of God—has spread nationwide. To some, ‘white-flight schools’ and ‘Christian schools’ are synonyms.”

That history echoes in our schooling debates. It pops up in conversations about today’s Christian—and especially white evangelical—parents’ attraction to private education because of ethical and theological concerns that the Trump administration’s robust executive orders on sex and gender may only temporarily allay. Our leaving public schools over curricula and policy on LGBTQ issues is reliably compared to Christians leaving public schools 60 years ago over race.

In a 2021 New York Times story, for example, religion reporter Ruth Graham made the connection explicit. The current moment is “the second Great Awakening in Christian education in the United States since the 1960s and ’70s,” a source told her. Given the specified timeline, Graham noted that the “previous ‘Great Awakening’ was spurred by a number of factors, starting when white Southern parents founded ‘segregation academies’ as a backlash to racial integration created by the Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education.”

Interrogating this comparison—this historical echo—is my chief interest here. It’s partly an intellectual interest. I think there’s a theological difference between these two waves of evangelical attraction to private schools.

I don’t have space to do all the theology here, but say for the sake of argument that contemporary evangelicals are right to believe that racism is an indefensible evil and the traditional Christian sexual ethic is correct. Assume with me that the former runs violently afoul of the God who is revealed in Christ and speaks in Scripture while the latter comports with God’s good will for human righteousness and flourishing.

In an important sense, for Christians, this distinction—that holding fast on sexual ethics is very different from embracing racism—answers the school choice comparison. For many, it may be enough to quiet the echo.

But I have to confess I’m not quite content to leave it there, because I can hear that echo too. I don’t make that comparison, but I understand why others do. Too many Christian parents cried wolf about the supposed dangers of integrated schooling. The cries were loud and long and sinful. Thus the rest of the village, rightly disgusted, is hesitant to listen this time around.

I have to confess too that I have a second reason for my interest. My kids were accepted to that Christian school for first grade this fall. They will receive a private, faith-based education, as I largely did. And my first school, the one that taught me to do sums and write cursive and devour chapter books, began as a segregation academy. Is there an echo not only in evangelical culture but in my own life?

I haven’t been able to dig up my yearbooks from that school, and its board declined to participate in this story. But from fuzzy childhood memories, I’m fairly certain the place had desegregated by the time I attended in the early 1990s.

My mom told me she wasn’t aware of the school’s history when she enrolled me; however, not being from the South, perhaps she simply didn’t recognize the clues.

Many Christian schools south of the Mason-Dixon Line began as my school did. Once integration became “inevitable, white segregationists throughout the South began to focus their energies on the establishment of separate schools,” explains historian Ansley L. Quiros in God with Us, a theological history of the civil rights struggle in a small Georgia town.

These segregation academies “would resist integration rulings and promote a particular theological vision for education.”

Often, the racism was overt. An enrollment application from Mississippi for the 1975–76 school year, for example, dispensed with all subtlety:

It is the belief of the Board of Directors of Council School Foundation that forced congregation of persons in social situations solely because they are of different races is a moral wrong. . . . Council School Foundation was founded upon and is operated in accordance with this fundamental ethical and educational concept. . . . The curriculum of Council School Foundation is designed solely for the educational responses of white children.

Others affected innocence. “We have had some blacks apply from the area,” a Christian school headmaster said in an Associated Press report in 1972, “but the pathetic situation is that they cannot make the preliminary testing.”

It may be tempting to brush this history away, to say, “Oh, but they weren’t really Christians.” Alas, they often were. As God with Us documents, they believed they were defending orthodoxy and Scripture itself against real threats to the faith.

“Christian theology contributed both to the moral power of the civil rights movement and to the staunch opposition it encountered,” Quiros wrote. Segregationists “felt they were acting out of the same impulses that motivated them to sing hymns, entreat the Almighty, and worship. They were upholding the sanctity of the Bible and the fundamentals of Christianity against Northern liberals.”

They were Christians, and they were wrong, and they left a stain on Christian education in America that has only partly faded.

Though there are many thoroughly integrated and even predominantly Black Christian schools in our country today—schools like the online Living Water School, Chicago’s Field School, or Imago Dei Neighborhood School in Richmond, Virginia—Christian schools’ student bodies, on average, remain whiter than the school-age population as a whole.

An ongoing reporting series on education and segregation by ProPublica has documented that it is not unheard of (particularly in the South’s Black Belt) for private schools to be more than 75 percentage points whiter than their communities. Numbers like that don’t happen by chance.

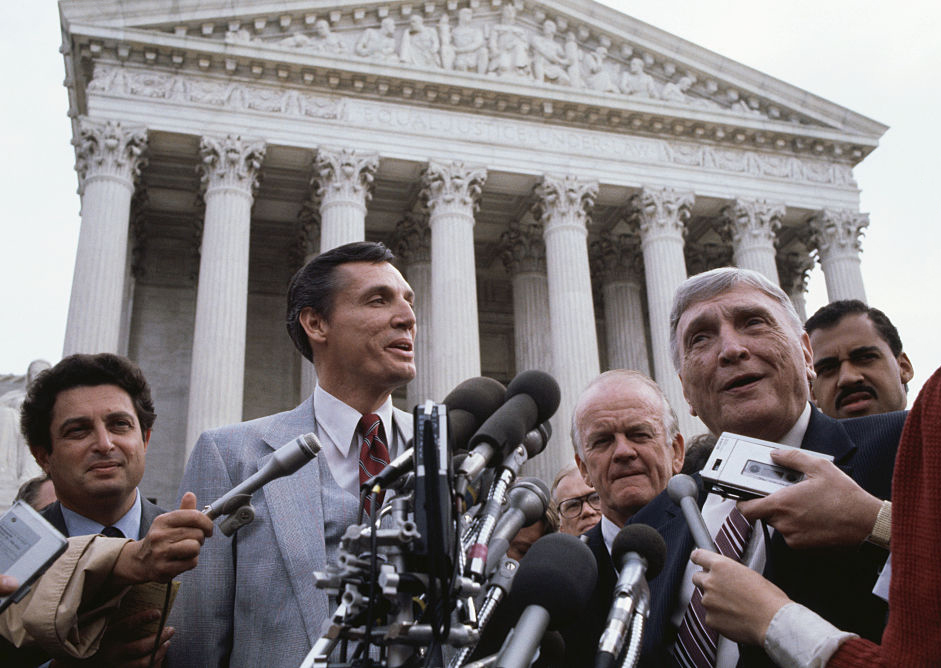

And while many Christian schools now publish racial nondiscrimination statements, it can be difficult to untangle the history and intent behind those pronouncements. Some were first issued defensively after the infamous Bob Jones University case of 1983, in which the Supreme Court held that the “government has a fundamental overriding interest in eradicating racial discrimination in education.”

Today, 47 percent of schoolchildren in America are white, and public schools nearly mirror the general public. Private schools are whiter (65%), and those the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) labels “Conservative Christian” are slightly whiter still (68% as of 2021). Christian schools seeking to diversify their student bodies often find that task easier said than done, though that’s not to suggest nothing has changed over the years. NCES data shows private schools are slowly but meaningfully diversifying, and conservative Christian schools don’t lag behind their secular and Catholic peers.

That’s true of my first school. In fact, that school has gone above and beyond the standard procedure of posting an affirmation of racial equality. Its statement is also confession, a frank recognition and repudiation of the circumstances surrounding the institution’s founding.

The websites I’ve browsed of other former segregation academies tend to paper over past sins with pictures of smiling Black students in monogrammed polos. To my school’s credit, it laments and repents.

My former school has a second statement on its website, bringing me back to the inevitable comparison. This statement is about sexuality and gender. It avows long-standing Christian understandings of marriage and biological sex in language buttressed by biblical references.

For many parents exploring private education, theology is one factor in a complex and often fraught decision-making process. Over the past half decade, pandemic policies and their aftershocks, reading instruction methods, and curricula on race and US history have all come to the fore alongside LGBTQ issues as widespread parental worries.

So why the particular attention to matters of sex and gender in the national conversation? Why is that the frequent comparison with the segregation era?

From the perspective of secular critics, I think it’s because, unlike other school-choice criteria, these two issues are understood as matters of unalterable identity. But on the evangelical side of the equation, I’ve come to think that the echo detectable here is not about repeated theological or political error. It’s not even about private education per se.

It’s about fear.

A characteristic expression of the anxiety in question comes from Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, who in 2022 coauthored Battle for the American Mind. It makes a candidly fearful case for Christian education.

“For many years, my fear was higher education,” Hegseth wrote, but he came to believe that “the real problem is high school, middle school, and now elementary school. The battlefield for the hearts and minds of our kids is the 16,000 hours they spend inside American classrooms from kindergarten to twelfth grade . . . it’s the 16,000-hour war.” And don’t think church is sufficient defense, Hegseth cautioned: “One hour on Sunday morning and one hour on Wednesday night at church is not enough.”

That last line made me chuckle, for I’ve approvingly quoted pastors making the exact same point. I wouldn’t argue for Christian schools with Hegseth’s Fox News–style bombast, but his desire for more intensive discipleship for his children is familiar.

It’s familiar to Christian educators too. University of Virginia sociologist Angel Adams Parham wrote at Comment in 2024,

As I have visited classical schools across the country, I have heard from heads of school who express concern that growing numbers of parents are coming to them not so much because they crave the pursuit of truth, goodness, and beauty that lies at the core of classical education at its best, but because they are beleaguered outcasts seeking shelter for themselves and their children from the ravages of critical race theory, “wokeism,” DEI [diversity, equality, and inclusion] initiatives, and more.

Fears of all kinds and levels of veracity get bundled together. And as Quiros observed in an interview with me, reinforcing all of them is the predilection to panic that defines much of America’s secular parenting culture today.

We live in enviable safety and prosperity, but we’re too scared to let nine-year-olds play in their own front yards. In that context, when the decision concerns things as important as education and sexual ethics, is it any wonder parents freak?

For the average Christian parent considering Christian education, then, I don’t think honing slam-dunk arguments about the sex-and-segregation comparison is the task at hand. Rather, it’s checking our motives for the distinction Parham drew: Do we want to enroll our kids in a Christian school for the good it offers? Or are we doing it because we’re scared?

The trick is being able to accurately parse the inclinations of our hearts. One useful indicator is how we think about insularity, which was brought to my attention by Tia Gaines, executive director of UnifiEd, a nonprofit supporting Christian schools. She also sits on the board of the Association of Christian Schools International (ACSI), a primary accreditor of US evangelical schools.

In one report from ACSI, Gaines told me, more than 400 Christian schools were assessed for 35 community characteristics. One of these “that had the biggest need for improvement was insularity,” Gaines said, which was defined as protecting students from the world’s brokenness, remaining aloof from the broader community, and/or lacking diversity in the student body.

“It was really interesting to see how Christian schools responded to that feedback,” Gaines said. “Some of them were surprised, and some were eager to address it. But some were like, ‘Well, yes, of course we have an insular culture. That’s the point. We want to shield our students and create a safe space for them, and that’s what our parents want.’ ”

That’s fear. But fearful pursuit of insularity doesn’t foster spiritual and intellectual maturity. It doesn’t leave room for iron to sharpen iron. It won’t teach our children, as the apostle Paul knew, that “neither death nor life, neither angels nor demons, neither the present nor the future, nor any powers, neither height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God that is in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Rom. 8:38–39). It won’t prepare them to be “as shrewd as snakes and as innocent as doves” (Matt. 10:16) in a world both wicked and wonderful.

Getty

GettyChristian schools do not have to be insular to be orthodox. Christian education does not have to be undergirded by fear or stuck on the sins of our fathers (Ezek. 18:20). We can follow the peculiar ethic of Jesus without withdrawing from the world. We can cry not “wolf” but “welcome.”

In the classroom, eschewing fearful insularity will mean examining what we teach and to whom we teach it. For classical schools, it will mean broadening the classics, as Parham argued in The Wall Street Journal, to include a wider array of time-tested ideas and voices, ancient and American alike. For all Christian schools, it will mean taking more seriously our own claims about loving the truth and learning to share it with the courage and cleverness of Paul on Mars Hill (Acts 17).

It will mean cultivating critical thinking alongside sound doctrine, and it’ll mean checking textbooks. This parental responsibility will look different than it would at a public school, but scrutiny is necessary still. Even Christian schools are run by sinners prone to wander from the truth.

For older students, Christian education shouldn’t play it safe. It should require encounters with hard history and perspectives from outside our cultures and the church itself, all under the guidance of faithful teachers.

“The truth sets us free,” said Anika Prather, the founder and administrator of a classical Christian school and the coauthor, with Parham, of The Black Intellectual Tradition. When Christ returns, she warned, “he’s not going to ask how many woke people you canceled. When we stand before the Lord, he’s going to say, ‘How many people did you reach for my gospel? And did you meet people where they were, or did you dehumanize them and not let them tell their story as a way of finding redemption and reconciliation?’ ”

Prather doesn’t shelter her students from secular thinkers or troubling history, she said. “I’m teaching my students, ‘Let’s bring this truth back to the Lord and figure out, “Lord, with this knowledge, how would you have me as a Christian navigate the world?” ’ This is what we teach our students,” she told me, “how we reach the next generation.”

And we should be aiming for everyone. “From Genesis to Revelation,” Prather said, God “has called the church to be a welcoming place for all ethnic backgrounds.” This call equally applies to schools that claim the name of Christ.

So where do these schools find their students? If they’re recruiting in local churches, which congregations make the cut? Black church traditions in America tend to be closely aligned with white evangelicals on core theology. If they’re not sending students to Christian schools, we should ask why. If the answer is tuition—for race and income are still correlated in this country—we should work to remove that barrier (Matt. 6:19–21). While many Black families remain skeptical of private schools, some would seize the opportunity for their children to have the good of Christian education.

“The manner in which most of us became Christian,” wrote theologians Stanley Hauerwas and William H. Willimon in their classic book Resident Aliens, “was by looking over someone else’s shoulder, emulating some admired older Christian, saying yes to and taking up a way of life that was made real and accessible through the witness of someone else.” We need those examples because the church and its ethics are indeed alien in a fallen world and because ethics, like language, are picked up through community immersion.

I moved around a lot as a child and consequently went through four Christian schools, one public school in America and one in China, and two years of homeschooling. Looking back, there’s much I could say in critique of my Christian schools. But I also recognize their many goods, not least their extension of the faithful examples in my home and church life.

As I make education decisions for my children, I want that faithful, communal immersion for them. Not because I’m afraid but because, for all its complications and all the work yet to be done, Christian schooling is a real good—a good I want for my kids and for my neighbors’ kids too. Of course we’re enrolling because it’s a Christian school.

Bonnie Kristian is the editorial director of ideas and books at Christianity Today.