A Christmas story.

My daughter wept on Christmas Eve. What should I say to the heart of my daughter? How should I comfort her? What should I tell her of tears, who has learned only their strength and perturbation, but knows no words for them?

Her name is Mary, truly. She is very young.

Therefore, she didn’t cry the older, bitter tears of disappointment. She hasn’t experienced the desolation of adults, who try so hard but find so little of spirit in the season, who cry unsatisfied, or merely for weariness.

Neither did she weep the tears of an oversold imagination, as the big-eyed children may. It wasn’t that she dreamed a present too beautiful to be real or expected my love to pay better than my purse. She’s greedy for my touch, is Mary, more than for my presents; and touching—Lord! I have much of that for Mary.

Nor was she sick on Christmas Eve. That were an easier pain for a father to console.

Nor was she hungry for any physical thing.

No, she was hungry for Odessa Williams, that old black lady—for her life. That’s why Mary cried. The child had come suddenly to the limits of the universe, and stood there, and had no other response for what she saw than tears, and then she wept into my breast, and I am her father. And should I be helpless before such tears? Or mute? Oh, what should I say to the heart of my daughter Mary?

This is what happened: It is the custom of our congregation to gather on the Sunday evening before Christmas—adults and youth and children, members of the choir particularly—to go out into the cold December night, and to carol the elderly. A common custom. Little elemental usually comes of it.

We bundle thick against the night wind. Our faces pinch—the white ones pink, the black ones (we are mostly black ones) pale. The kids can hardly walk for all their clothing, but run nonetheless. And then we sing a boisterous noise. Our breath puffs clouds at our lips. The old people smile through their windows and nod to the singing and close their eyes and seem to dream a little of the past. We lift our keys and jangle them to the chorus of “Jingle Bells.” And sometimes, sometimes those sweetest voices among us will sing alone. Young “Dee Dee” will take a descant trip on “Silent Night” that makes the rest of us drop our eyes and wonder at so clear and crystalline a melody; and Tim Moore will set himself free, and us and all the night streets of the city, with “O Holy Night”; he will, with an almighty voice, ride to heaven on the song and then return to earth in the merest murmur, “When Christ was born, when Christ was born”—and we will find the tears freezing on our eyelashes, moved by beauty on a cold, dark, winter’s sidewalk.

But these are good tears, and not the tears of my Mary.

We went, one such Sunday evening, December the twentieth, through a snowless dark, to Saint Mary’s Hospital. We divided ourselves among the wards. We carried our caroling to those members who were patients there. And I, with Mary and Dee Dee and Tim Moore and a handful of the children who sang in the choir, slipped finally into Odessa Williams’s room, to sing to her.

She had a curtain pulled round her bed; therefore, we had to stand right close. And though the light was dim at the bedstead, we could see the old lady’s face. The sight made the children solemn and quiet, quiet. Her brown cheeks had gone to parchment, were sunken, her temples scalloped; her hair and her arms together were most thin, her nails too long, her eyes beclouded. Odessa was dying of cancer.

This was the first time that the children had met her. They gazed, and they waited to be led.

As her pastor, I had been visiting Odessa for years, first in her apartment, then in a nursing home, finally here, a long descent. But her soul belonged fiercely to Grace Church, and she had, at her distance, followed every event of the congregation. She set her jaw (when her teeth were in) to speak of that church; and she worked her gums (when they were not) busily, passionately, when she worried for its future. Because of her wasting disease, she had never appeared among the people; but that did not mean she loved them any less. Simply, they were unaware how much she did love them. Yet Odessa could communicate such a message with sudden speed and indelibly.

So the children, in dim yellow light, were circled round a stranger, were staring at a stranger, delicate, old, and dying, lying on her back.

Odessa, for her part, said nothing. She stared back at them.

“Sing,” I said to the children. “What’s this? Y’all gone munching on your tongues? Sing the same as you always do. Sing for Miz Williams.”

And they did, that wide-eyed ring of children.

One by one they sang the carols everyone knew, though children had no keys to jangle. One by one they relaxed, and their faces melted, and I saw that my Mary’s eyes went bright and sparkled—and she smiled, and she was smiling on Odessa Williams. The children gave the lady an innocent concert, as clean and light as snow.

Odessa, too, began to smile.

For that smile, for the gladness in an old lady’s face, I whispered, “Dee Dee, sing ‘Silent Night’ once more.”

Dear Dee Dee! That child, as dark as the shadows around her, stroked the very air as though it were a chime of glass. (Dee Dee, I love you!) So high she took her crystal voice, so long she held the notes, that the rest of the children unconsciously hummed and harmonized with her, and they began to sway together, and for a moment they lost themselves in the song.

Yet, Odessa found them. Odessa snared those children. Even while they still were singing, Odessa drew them to herself. And then their mouths were singing the hymn, but their eyes were fixed on her.

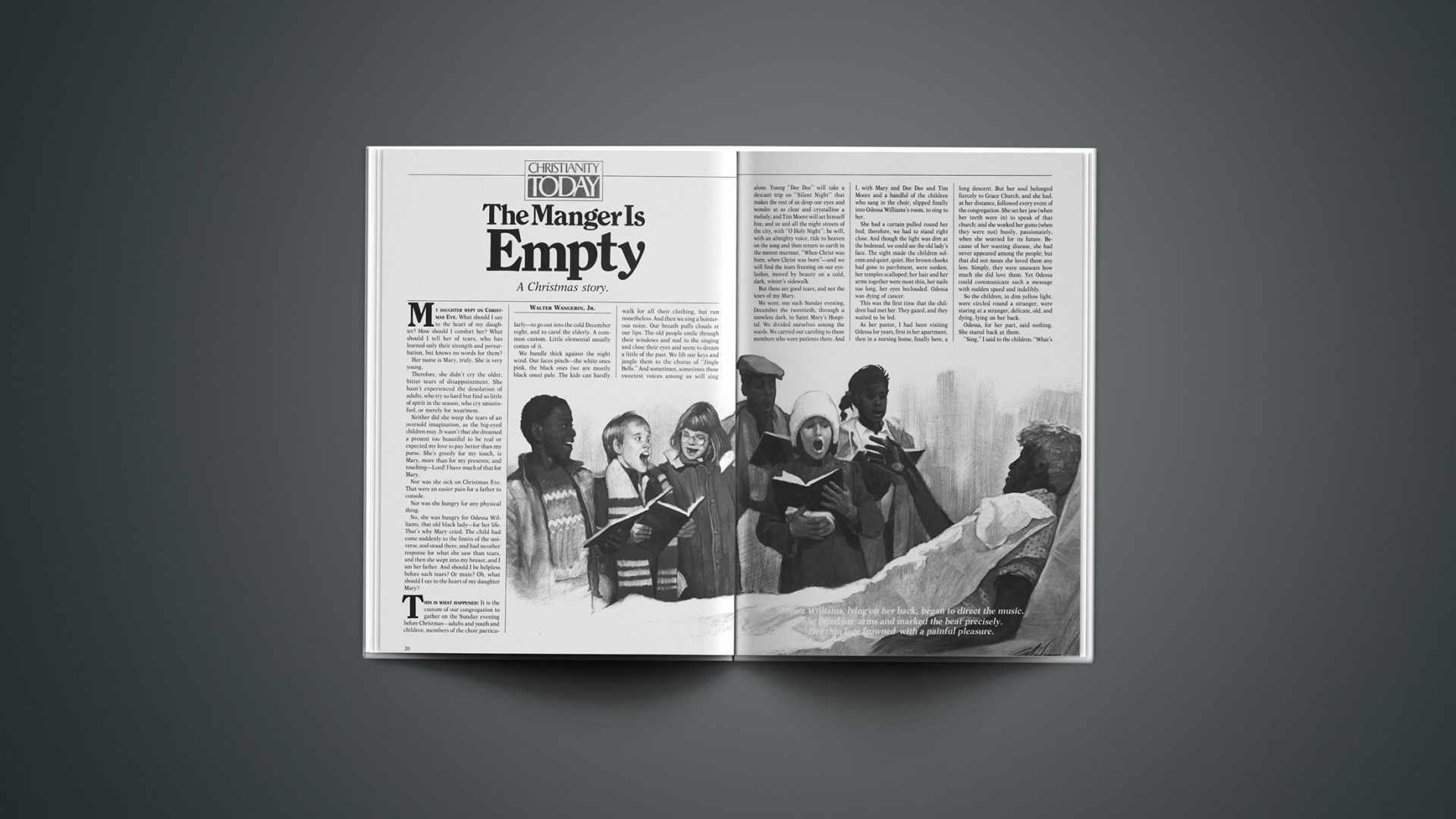

Odessa Williams, lying on her back, began to direct the music.

She lifted her arms and marked the beat precisely; her lank hands virtually shaped the tone of Dee Dee’s descant; and her thin face frowned with a painful pleasure. She pursed her lips as though tasting something celestial and delicious, so the children thought themselves marvelous; and she let another music smoke at her nostrils. The lady took them. The lady carried them. The lady led them meek to the end of their carol and to a perfect silence; and then they stood there round her bed, astonished, each one of them the possession of Odessa Williams, restrained. And waiting.

Oh, what a power of matriarchal authority was here, keenly alive!

Nor did she disappoint them. For she began, in a low and husky voice, to talk. No, Odessa preached.

“Oh, children, you my choir,” she said. “Oh, choir, you my children for sure, every las’ one of you. And listen me.” She caught them one by one with her barbed eyes. “Ain’ no one stand in front of you for goodness, no! You the bes’, babies! You the final best.”

The children gazed at her, and the children believed her absolutely, and my Mary, too, believed what she was hearing, heart and soul.

“Listen me,” Odessa said. “When you sing, wherever you go to sing, whoever’s sittin’ down in front of you when you sing—I’m there with you. I tell you truly: I alluz been with you, I alluz will be. And how can I say such a mackulous thing?” She lowered her voice. Her eyelids drooped a minimal degree. “Why, ‘cause we in Jesus. Babies, babies, we be in Jesus, old ones, young ones, us and you together. Jesus keep us in his bosom, and Jesus, no—he don’t never let us go. Never. Never. Not ever—”

So spoke Odessa in the dim long light. So said the lady with such conviction and with such a determined love for children whom she’d never met till now, but whom she’d followed with her heart, that these same children rolled tears from their wide-open eyes, and they were not ashamed.

They touched the hump of her toes beneath the hospital blankets. Stumpy black fingers, baby affection, and smiles.

And my Mary’s eyes I saw to glisten. The lady had won my daughter. In that holy moment, so close upon the Holy Day, so brief and so lasting at once, Mary came to love Odessa Williams completely. This is the power of a wise love wisely expressed: it can transfigure a heart, suddenly, forever.

But even these tears, shed Sunday evening in the hospital room, are not the tears that wanted my comforting. They are themselves a comfort. No, the tears that I had to speak to were the next my daughter wept. Those, they came on Christmas Eve.

Three days before Christ’s birthday, Odessa died. It was a long time coming. It was quick when it came. She died that Tuesday, the twenty-second of December. On Wednesday her body was in the care of the undertaker. The funeral was set for 11 in the morning, Thursday, the twenty-fourth. There was no alternative; the mortuary would be closed both Friday and the weekend. Throughout these arrangements—while at the same time directing preparations for special seasonal services—I was more pastor than father, more administrator than wise.

Well, it was a frightfully busy, hectic week. This was the very crush of the holidays, after all, and my doubled labor had just been trebled.

Not brutally, but somewhat hastily at lunch on Wednesday I told my children that Miz Williams had died. They were eating soup. This was not an uncommon piece of news for me to bear them: the congregation has its share of the elderly.

Mary, I barely noticed, ceased eating.

I wiped my mouth and rose from the table.

Mary stopped me briefly with a question and a statement. Staring at her soup, she said, “Is it going to snow tomorrow?”

I said, “I don’t know, Mary. How would I know that?”

And she said, “I want to go to the funeral.”

So: she was considering what to wear against the weather. I said, “Fine,” and left.

Thursday came grey and hard and cold and windless. It gave a pewter light. It made no shadow. The sky was sullen, draining color even from the naked trees. I walked to church. How still was all the earth around me—

It is the custom of our congregation, before a funeral, to set the casket immediately in front of the chancel and then to leave it open an hour until the service itself. People move silently up the aisle for a final viewing, singly or else in small groups, strangers to me who look and think and leave again. Near the time appointed for the service, they do not leave, but find seats and wait in silence. I robe ten minutes to the hour. I stand at the back of the church and greet them.

And so it was that I met my Mary at the door. In fact, she was standing outside the door when others pushed in past her.

“Mary?” I said. “Are you coming in?”

She looked at me a moment. “Dad,” she whispered earnestly, as though it were a dreadful secret, “it’s snowing.”

It was. A light powder grew at the roots of the grasses, a darker powder filled the air. The day was too cold for flakes—just a universal sifting of powder that seemed to isolate every living thing.

“Dad,” Mary repeated, gazing at me, and now it was a grievous voice, but what was I supposed to do? “It’s snowing!”

“Come, Mary. We haven’t much time. Come in.”

My daughter and I walked down the aisle to the chancel and the casket, and she was eight years old, then, and I was robed. People sat in the pews like sparrows on telephone wires, huddled under feathers, watching dark-eyed.

Mary slowed and paused at the casket and murmured, “Oh, no.”

Odessa’s eyes were closed, her lips pale; her skin seemed pressed into place, and the bridge of her nose suffered glasses. Had Odessa worn glasses? Yes, she had. But these were perched on her face slightly askew, unnaturally, so that one became sadly, sadly aware of eyeglasses for the first time. What belonged to the old lady any more, and what did not?

These were my speculations.

Mary had her own. She reached out and touched Odessa’s long fingers, crossed waxy at the breast. “Oh, no,” she whispered. The child bent and brushed those fingers with her cheek, then suddenly stood erect again.

“Oh, no,” Mary said, and she looked at me, and she did not blink, but she began to cry. “Dad,” she whispered. “Miz Williams is so cold. Dad,” wept Mary, “but it’s snowing outside—it’s snowing in Miz Williams’ grave!” All at once Mary buried her face in my robes, and I felt the pressure of her forehead and all her grief against my chest—and I was a father again, and my own throat swallowed and my eyes burned.

“Dad,” sobbed Mary. “Dad, Dad, it’s Christmas Eve!”

These were the tears. These were the tears my daughter cried at Christmas. God in heaven, what do I say to tears like these? It is death my Mary met. It’s the end of things, that things have an end, good things, kind and blessed things, things new and rare and precious: that love has an end; that people have an end; that Odessa Williams, the fierce old lady who seized the heart of my Mary and squeezed it and possessed it but four days ago, who was so real in dim light, waving her arms, that she has an end, ended, is gone, is dead.

How do I comfort these tears? What do I say to the heart of my daughter?

Jesus, Jesus, pity me. I said nothing.

I knelt down. I took Mary’s streaming face between my hands. But she so pierced me with the questions in her eyes that I couldn’t look at her, and I gathered her to myself, and I held her tightly, I held her hard, until I’d wrung the sobbing from her body; and I released her.

I watched her go back down the aisle and turn into a pew and sit. It was a silent Mary who went. She sat by her mother, but she asked no questions any more. Why should she, sad Mary, when there were no answers given?

So, the funeral. And so, the sermon.

“But there will be no gloom for her that was in anguish.” Isaiah. “The people who walked in darkness have seen a great light.” Prophecy and truth. “For to us a child is born, to us a son is given”—Christmas. But what were Isaiah and prophecy and all the sustaining truths of the faith to my daughter Mary? Nothing. Odessa had been something to her, but Odessa was dead. The casket was closed. Death was something to her now, and maybe the only thing.

The weather at graveside was grey and cold and snowing. The people stood in coats and shivered.

Mary said not a word nor held her mother’s hand nor looked at me.

Neither was she crying any more.

It is the custom of our family to open our gifts late Christmas Eve. I wondered, that afternoon, whether we oughtn’t vary custom this year, for Mary’s sake. She was still in her gloom and anguish, separated from us all by silence. There must have been a tumult of thought in her brain, but none of it showed on an eight-year-old face made severe. Oh, Mary, what joy will you have in presents, now? How frivolous the ribbons and wrappings would seem to one so thoughtful.

But that private custom of ours depended upon another custom of the congregation: we would not open the gifts until first we’d participated in the children’s Christmas service at church. This service gave me the greatest hesitation, because my Mary was to be the Mary in it, the mother of the infant Jesus. Could she accomplish so public a thing in so private a mood?

I asked her. “Mary, do you think we should get another Mary?

Slowly she shook her head. “No,” she said. “I’m Mary.”

Mary, Mary, so much Mary—but I wish you weren’t sad. I wish I had a word for you. Pastor, father, old and mute. Mary, forgive me, the heart of my daughter. It is not a kind world after all. Not even the holidays can draw a veil across the truth and pretend the happiness that is not there. Mary, bold Mary—“You are Mary,” I said. “I’ll be with you. It’ll be all right.”

We drove to church. The snow lay a loose inch on the ground. It swirled in snow-devils behind the cars ahead of us. It held the grey light of the city near the earth, though this was now nighttime, and dark. Surely, the snow had covered Odessa’s grave as well, a silent, seamless sheet of no warmth whatsoever.

Ah, these should have been my Mary’s thoughts, not mine.

The church sanctuary was full of a yellow light and noise, transfigured utterly from the low, funereal whispers of the morning. People threw back their heads and laughed. Parents chatted. Children darted, making ready for their pageant, each at various stages of dress, caught halfway between this age’s blue jeans and the shepherds’ robes of two millenia ago. Children were breathless. But Mary and I moved through the contumely like sprites, unnoticed and unnoticing. I was filled with her sorrow. She seemed simply empty.

In time the actors found their proper places, and the glad pageant began.

“My soul,” said Mary, both Marys before a little Elizabeth—but she said it so quietly that few could hear and my own heart yearned for her—“magnifies the Lord, and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior—”

And so: the child was surviving. But she was not rejoicing.

The angels came and giggled and sang and left.

A decree went out.

Another song was sung.

And then three moved into the chancel: Joseph and Mary and one other child to carry the manger, a wooden trough filled with old straw and a floppy doll.

The pageant proceeded, but I lost it entirely in watching my daughter.

For Mary began to frown fiercely on the manger in front of her—not at all like the proud and beaming parent she was supposed to portray. At the manger, she was staring, which stood in precisely the same spot where Odessa’s casket had sat that morning; and one was open as the other had been, and each held the figure of a human. Mary frowned so hard at it that I thought she would break into tears again, and my mind raced over things to do when she couldn’t control herself any more.

But Mary did not cry!

While shepherds kept watch over their flocks by night, my Mary played a part that no one had written into the script. The girl reached into the manger and touched the doll, thoughtfully. What are you thinking? Then, as though it were a decision, she took the doll out by its toes and stood up and walked down the chancel steps. Mary, where are you going? I folded my hands on account of her and yearned to hold her, to hide her, to protect her. But she carried the doll away into the darkened sacristy and disappeared. Mary? Mary? In a moment the child emerged again with nothing at all. She returned to the manger quickly, and she knelt down and she gazed upon the empty straw with her palms together like the first Mary, full of adoration. And her face—Mary, my Mary, your face was radiant then!

O Mary, how I love you!

Not quite suddenly there was in the chancel a multitude of the childish host praising God and saying, “Glory to God in the highest!” But Mary knelt unmoved among them, and her eight-year-old face was smiling, and there was the glistening of tears on her cheeks, but they were not unhappy, and the manger, open, empty, seemed the cause of them.

My soul magnifies the Lord! My spirit rejoices in God my Savior, for he has regarded the low estate of his handmaiden. Mary, what do you see? What do you know that your father could not say to the heart of his daughter? Mary, mother of the infant Jesus, teach me too!

She sat beside me in the car when we drove home. A sifting snow made cones below the streetlights. It blew lightly across the windshield and closed us in.

Mary said, “Dad?”

I said, “What.”

She said, “Dad, Jesus wasn’t in the manger. That wasn’t Jesus. That was a doll.” Oh, Mary: all things are struck real for you now, and there is no pretending any more. It was a doll indeed.

So, death reveals realities—

She said, “Jesus, he doesn’t have to be in a manger, does he? He goes back and forth, doesn’t he? He came from heaven, and he was borned here; but when he was done he went back to heaven again, and because he came and went he can be coming and going all the time, right?”

“Right,” I whispered. Teach me, little child. Teach me this Christmas gladness that you know.

“The manger is empty,” Mary said. And then she said, “Dad, Miz Williams’ box is empty, too. We don’t have to worry about the snow.” The next wonder my daughter whispered softly, as though peeping at presents; “It’s only a doll in her box. It’s like a big doll, Dad, and we put it away today. If Jesus can cross, if Jesus can go across, then Miz Williams, she crossed the same way, too, with Jesus—”

And Jesus, no—he don’t never let us go. Never.

“Dad?” said Mary, my Mary, the Mary who could ponder so much in her heart. “Why are you crying?”

Babies, babies, we be in Jesus, old ones, young ones, us and you together. Jesus keep us in his bosom, and Jesus, no—he don’t never let go. Never. Never. Not ever.

“Because I’ve got no other words to say,” I said to Mary. “I haven’t had the words for some time, now.”

“Dad?”

“What.”

“Don’t cry. I can talk for both of us.”

It always was; it always will be; it was in the fullness of time when the Christ child first was born; it was in 1981 when my daughter taught me the times on Christmas Eve; it is in every celebration of Jesus’ crossings back and forth; and it shall be forever—that this is the power of a wise love wisely expressed: it can transfigure the heart, suddenly, forever.