It seems to me that many of us read the parable of the Good Samaritan with an unstated understanding that its basic message is “For crying out loud, just don’t be a jerk.”

The Sunday school storyboard unfolds in our mind’s eye. A poor, innocent guy has been brutally beaten, and any reasonably moral person would be horrified. The priest and the Levite see him and pass by on the other side of the road. We are astonished by their callous behavior. Surely this is not what any decent human being would do! How can they bear to leave the poor man lying on the side of the road? We unimaginatively insert ourselves into the story in the role of the Good Samaritan, certain that if this event were ever to present itself in our daily lives, we would obviously do the right thing.

In my own experience, living this out went quite differently.

I am driving back to my home in the rural interior of the East African country of Burundi, where I live and work as a missionary physician. The past few days have been a marathon of high-stress cross-cultural and multilingual meetings regarding an international accreditation for our medical school. Preparing for my three-hour trip home, I am utterly spent. I want nothing more than to see my family and share the takeout food that is currently sitting on my passenger seat’s floorboard.

My car winds up the narrow mountain roads lined with banana and palm nut trees. This dangerous journey, with its steep drop-offs and limited visibility, was a terror for the first few years that I lived here, but now it is more or less commonplace. As I drive, I pray that the hours of the trip lighten a bit of the load that I’m feeling.

As the road turns yet again, I see a commotion in front of me: shattered glass, a smashed motorcycle, and a chaotic movement of people on the roadside. Two young men are dragging a body away from the motorcycle on the tarmac, one holding a leg and the other an arm, to the narrow gravel shoulder of the road overlooking a steep ravine.

I realize that this accident has happened just moments ago. I am a sudden storm of conviction and indecision. So much in me wants to keep driving. After all, no one at the scene will know the obligation I feel to help. The stakes are high for me too. I need to get home before nightfall makes driving unsafe. Getting involved could mean getting extorted or even blamed for the wreck. The only thing that makes me stop is the oath I took when I became a doctor, and driving by now would all but render that meaningless. I know intimately the lack of emergency services in this area and that there is no other help.

I pull over and get out. “I’m a doctor,” I say in halting Kirundi. I kneel by the unconscious man, who has a large head wound with thick blood forming a trail back to where he was lying in the road. I notice that he’s breathing, his pupils react to light, and his pulse is good. He could be all right if he gets to a hospital.

“Does anyone here speak French?” I ask the young men next to me. A few seconds later, a different man emerges from the crowd and greets me in French. “Is anyone else hurt?” I ask.

As he points to a small crowd 20 meters away, I marvel that I haven’t yet noticed the loud wailing coming from that direction. I go over to look. A young woman screams as I inspect her big open tibia fracture. The leg injury is serious, but she’s obviously conscious and breathing well.

I’ve done all that I can at the roadside. “What are you going to do?” I ask the young French speaker. His face has the too-familiar look of helplessness—of having no transportation, no money, and no one to turn to because everyone around you is in the same boat.

I realize again that they are not waiting on any kind of emergency service. They are maybe hoping that a taxi will take someone somewhere in the next six hours, but that could easily be too late, especially for the unconscious man.

“Look, I have room to take one of them to the hospital up the road a ways,” I offer.

“Take the girl!” the man by me immediately replies.

“The guy is sicker,” I counter.

“He’s already dead.”

This is so obviously untrue that I’m starting to get angry. “He’s breathing!” My voice rises.

The man looks down the road at the abandoned body, as if considering him for the first time. My suspicion is that the motorcycle driver is a John Doe to the bystanders and the injured (but less critical) woman is a friend, maybe even a family member.

I sigh. “Look, let me try and get the seats all flat in my car. Maybe I can take both of them.” I wrestle with my bags and the seats in my RAV4. There is just enough room for the two injured people to lie down and for a male relative to crouch next to the injured woman. The four of us are ready to go.

By this point, the local police have arrived on the scene. I try to explain the urgency of getting the injured people to the hospital. But the officers want me to remain at the scene to give some kind of statement and pass on my contact information. I definitely have no desire to get entangled in a local police affair. Finally, I persuade them to let me go, and I hurry on my way with my car full of bodies.

The French speaker stops me. “Don’t go up the road to that nearby hospital. Please. Please take them back down to the city to a better hospital.” Backtracking all the way back to the city means that I won’t be able to get home before sundown as planned. But I know he’s right. I’ve been to that nearby hospital, and it won’t be able to help. He tells me which hospital to take them to. I know the place, and I agree.

It’s on the drive down that I start to realize we’re acting out the parable of the Good Samaritan. There were injured folks on the side of the road, and I faced a decision to either pass by like everyone else or take them to medical care. The similarities are striking, so why didn’t I notice them before?

For one thing, it doesn’t feel at all like I thought it would. I’m so angry and scared and tired. The woman in the back keeps screaming, “I’m dying!” in Kirundi, and I want to scream back at her that her yelling isn’t helping anything.

Why today? I was already so worn out. In my mind, the Good Samaritan was always some kind of blank slate, with no preexisting burdens of his own and no urgent need to get about his own business, judging by the way he put all of that aside. I saw his generosity but assumed it had come from a margin that I don’t have. If I had that kind of margin, I would react as graciously as he had. But when is any real person really in that situation?

Maybe following the Good Samaritan means recognizing that our own burdens, our own fatigue, and even our own needs accompany us right into the story.

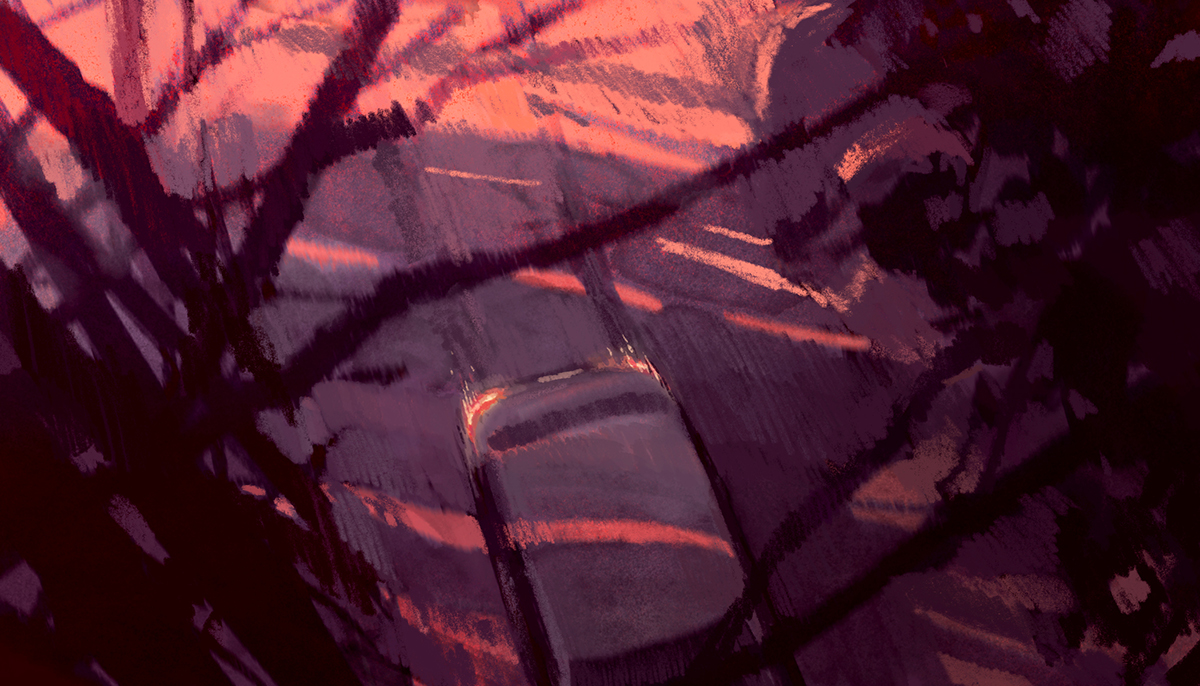

Illustration by Hokyoung Kim

Illustration by Hokyoung KimThe drive down the mountain is harrowing. I have critically injured strangers in my back seat for whom time is running out. I also have a treacherously winding road with narrow shoulders, numerous potholes, crowds of pedestrians and bicycles sharing the lanes, and trucks puttering down the mountain at ten kilometers per hour. Trying to rush this road takes a normally risky drive to a level of crazy that I have to consciously back myself down from. At one point, I slam on my brakes, and the hood of my car stops slightly underneath the overhanging back end of a semi-truck. I take a deep breath and start praying aloud in English to drown out the yelling from the woman in the back.

I think about risk. Driving off with these people in my car could still mean getting embroiled with the local police, which I’ve done before and really would like to avoid. Going quickly down the mountain could mean putting my own life in jeopardy. One of my friends here told me about driving to the airport at night and seeing a body lying on the side of the road. As he wondered whether to stop, he remembered stories in which such a body was a ruse to get people to stop so that they could be attacked and robbed. He drove on. I totally understand.

Any of these implications finds a ready place in the parable. Did the Samaritan fear a scam? It wouldn’t have been unreasonable. Was he going to get entangled with local law enforcement by trying to help? I always assumed that the inn was farther down the same road, but maybe the Samaritan had to backtrack like me and thus expose himself to the not-insignificant dangers of travel at night.

My life here in Burundi gives me ample information to assess the situation. What might happen to me or others if I get involved? What is the likely benefit if I plunge my hands in? Assessment is wise, but risk itself cannot mean that we are not called to enter into the story. Maybe following the Good Samaritan also means accepting that some risk—not just cost or inconvenience—will inevitably follow.

With relief, I arrive in the city and head to the hospital. I drive onto the property through a gate and eventually find the emergency area. I park the car and jump out, stopping the first guy I see in scrubs.

“I have two trauma patients in my car. An unconscious man with a head wound and a woman with an open tibia fracture.”

He stares back at me. I try again, to no avail. After a couple of minutes, the doctor who seems to be in charge comes out. I lead him quickly to the car and open the back hatch. The guy is still unconscious. The woman is calmer for a moment, leaning against her relative who is crouched next to her. I’m looking around for a stretcher or a wheelchair. I can’t understand why, after I risked my life rushing down the mountain, no one is acting.

The doctor starts chatting calmly with the conscious people in my car. I can understand that he is asking about money. He clucks his tongue regretfully and turns to me. “Ah, you see, there is a problem. They have no money. So we cannot care for them.”

This is essentially a private hospital, and I understand that a hospital can’t remain solvent without some income to cover its services. Whether a payment is expected or not, I never imagined a physician would lack motivation to care in an emergency situation such as this. I realize now why no one has gotten the injured people out of my car. The hospital wants to ensure that I will take them away again.

I try to pull rank. I explain my role in medical leadership in the area and ask if he’s okay with me calling his superior and recounting his words. He looks back at me with the overly calm stare of someone who has this conversation every day. “Absolutely,” he says.

“Well, where can I take them?”

“I don’t know.”

“Can I take them to the other hospital just down the road?”

“I don’t know.”

I slam the trunk, get into my car, and drive out the gate without another word.

This is not what I signed up for. My job was to get these people to the hospital, where my generosity would be appreciated and someone else would take it from there. But in for an inch, in for a mile—not because I have any choice; I’m stuck.

Could this have happened to the Good Samaritan? I always pictured the innkeeper with a smile, but who wants a half-dead John Doe in their establishment, even if his expenses are covered? Was that inn the first one the Good Samaritan tried, or did he have to shop around and beg for a while? What if he tried other inns and found they didn’t want a bloody, unconscious man who might scare off their better clientele (like priests and Levites)? What if no one but the Samaritan cared if the injured man lived or died?

As the complexities of living out the parable unfold, I realize more and more that following the Good Samaritan may mean getting in deeper and being more alone than I imagined.

Down the road, I pull into the other hospital. I can’t even find the emergency room without significant help. It’s a small building behind the rest of the campus, like a 30-years-later afterthought. I pull in, wondering what my reception will be. I wander into the ER, asking for a nurse to come out to my car. I explain the situation as a small crowd gathers. The nurse looks in the back of the car and disappears into the ER without another word. I’m not sure what’s going on.

At least 10 minutes later, a stretcher appears, and the injured woman climbs on. She disappears inside the hospital with the family member who rode down with her. The only one left is the still-unconscious man. He is still breathing, and I’m glad to see that he’s starting to groan a bit. Embarrassingly, I keep thinking about how close I am to having my car free again.

A lady standing nearby asks, “How do you know these people?”

“I don’t. I was just driving by, and they needed to get to a hospital.”

“God bless you.”

I just want to cry.

After the stretcher returns and the man is loaded on, I ask to see the family member who rode down with me. I want to give him a bit of money discreetly to cover some initial expenses, but I’m afraid he’ll use it all for his relative and neglect the man.

I decide to trade discretion for accountability and avoid a long discussion about how much money he needs. First I get in the driver’s seat to secure my getaway, and then I roll down the window. I hold up the money for the family member and the omnipresent surrounding crowd to see. “Half of this is for your family, but the other half is for the other guy.” A random person from the crowd pipes up that he understands and that everyone here sees that this man needs to spend half of the money on the motorcyclist. I give a brief nod, hand the relative the money, and drive off.

I think about how the Good Samaritan promised to return and cover all additional expenses. I live three hours away and have my own hospital of patients. I guess the Good Samaritan may have also had such a level of responsibility. Regardless, I have no intention of coming back.

Illustration by Hokyoung Kim

Illustration by Hokyoung KimThe drive home is stressful as night falls but thankfully uneventful. As I drive past the accident site, I try to shield my face. I think the crowd (which is still there) may have recognized me, but I drive on.

Late at night, I arrive at my house, collapsing onto the couch, wanting to find tears but feeling too overwhelmed. What just happened? I’m not really sure. My medical assessment is that the lives of a couple of people might have been transformed, but trying to follow the Good Samaritan was utterly different than what I imagined.

“Who is my neighbor?” the man asked Jesus to spark the whole story. Go and be a neighbor, Jesus concluded (Luke 10:25–37).

This story hurt me. My emotional well was near empty when the whole affair started, and I ended up scraping the dry bottom repeatedly. I would decide to engage up to a certain point, and whenever I reached that point, I was asked to go further, again and again.

But as Martin Luther King Jr. stated in his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech, the priest and the Levite ask, “If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?” The Samaritan asks, “If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?” The parable calls us out of ourselves into a work of sacrifice for another. To love is to sacrifice, and sacrifice hurts.

There were no heroics. Instead, it was a mess. A jumble of my own burdens and the unexpected burdens of others. Irreducible risk that came with entering a violent and needy situation. A lonely experience that took far more from me than I signed up for.

Yet this seems to be what the parable actually looks like. Before this experience, if you had asked me to respond to the call of the Good Samaritan parable, I think I would have assented, even if hesitatingly.

But I now see my previous assumptions. I assumed such an opportunity for sacrifice would come at a time that was, if not perfect for me, maybe optimal or at least not so inconvenient. I assumed that the innkeeper would greet me with a smile and that others would rally to collaborate. I assumed the cost would be more financial than emotional. I assumed stepping out in obedience, even if difficult, would end with a feeling of satisfaction, like the heavy breathing and sweat that come at the end of a good workout.

But it’s not like that. I can say as a medical educator in one of the world’s poorest nations that emotional costs are high whether you’re trying to help one or two individual people on the side of the road or addressing systemic problems that lead to people lying injured on the side of the road. Striving for such upstream system changes is wise but also messy.

Crises come when we pray they wouldn’t, and the risks and the costs may mount well beyond what we expect as we get pulled deeper and deeper into the fray.

I am reminded of these costs often, as I see the dried blood I couldn’t quite get out of the upholstery of our RAV4. But this mess and heartache is how the parable actually plays out.

If I could go back and do it again, I would remind myself of some other words of Jesus that never occurred to me that day. Jesus tells us in Matthew 25:40 that serving people in their need is serving him. He was present in my trunk, unconscious. He was present in the woman screaming.

My sacrifice was in fact an opportunity to carry my Lord around town until a suitable place could be found.

Let’s not wait for some imaginary moment when circumstances and moods convene. Let us receive the inevitable injuries of our fallen world as the painful yet blessed opportunities that they are.

Let us evaluate the risks of Christian love together and support each other in our pain. Let us remember that our Lord is present in those who are in need—and in us, despite our own inadequacy.

Eric McLaughlin is a missionary doctor in Burundi and the author of Promises in the Dark: Walking with Those in Need Without Losing Heart.