In this series

“Next to the Word of God, music deserves the highest praise,” Luther declared. He thus stood in sharp contrast to other reformers of his era.

Ulrich Zwingli, leader of the new church in Zurich, was a trained musician. Yet under his influence, Zurich’s magistrates banned all playing of organs, and some of Zwingli’s followers went about smashing organs in their churches. Though Zwingli later permitted some vocal music, he rejected instrumental music.

John Calvin, though he considered music a gift of God, saw it as a gift only in the worldly domain. Thus, its role in the church was severely limited. He considered instrumental music “senseless and absurd” and disallowed harmonies. Only unison singing of the Psalms was permitted.

Not so for Martin Luther. “I am not of the opinion,” he wrote, “that all arts are to be cast down and destroyed on account of the gospel, as some fanatics protest; on the other hand, I would gladly see all arts, especially music, in the service of him who has given and created them.”

Music in congregational worship remains one of Luther’s most enduring legacies. “Who doubts,” he said, “that originally all the people sang these which now only the choir sings or responds to while the bishop is consecrating?”

In fact, Luther’s hymns—especially “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God”—are the only direct contact many people have with Luther. Modern Lutheran hymnals may contain twenty or more of his hymns, and many non-Lutheran hymnals include several.

What were Luther’s beliefs about music? What role did it play in worship? And what did Luther himself contribute musically to the church?

In Praise of Music

By the sixteenth century, musical composition had developed into a high art, and Luther himself was a well-trained musician. He possessed a fine voice, played the lute, and even tried his hand at advanced composition. He was acquainted with the works of the day’s leading composers, like Josquin des Pres: “God has preached the gospel through music, as may be seen in Josquin des Prez, all of whose compositions flow freely, gently, and cheerfully, are not forced or cramped by rules, and are like the song of the finch.”

Luther observed that only humans have been given the gift of language and the gift of song. This shows we are to “praise God with both word and music.” Furthermore, music is a vehicle for proclaiming the Word of God. Luther loved to cite examples like Moses, who praised God in song following the crossing of the Red Sea, and David, who composed many of the psalms.

He said, “I always loved music; whoso has skill in this art, is of a good temperament, fitted for all things. We must teach music in schools; a schoolmaster ought to have skill in music, or I would not regard him; neither should we ordain young men as preachers, unless they have been well exercised in music.”

Conservative Reformer

Luther’s high regard for music was matched by a cautious attitude when it came to reforming worship practices. “It is not now, nor has it ever been, in our mind to abolish entirely the whole formal cultus [worship] of God,” he once wrote, “but to cleanse that which is in use, which has been vitiated by most abominable additions, and to point out a pious use.”

He had no desire simply to throw out the liturgy of the church. The cry for mercy in the Kyrie, the praise of Christ in the Gloria in Excelsis, the witness to the apostolic faith in the Credo, the proclamation of Christ’s all-sufficient sacrifice for the sins of the world in the Agnus Dei—these were vital ingredients for the faithful proclamation of justification by grace alone.

Still, Luther sought reform. One of his concerns was the predominant use of Latin in the service. The common people needed to hear and sing the Word of God in their own tongue—German—so they might be edified. In one of his earliest liturgical writings, Luther said, “Let everything be done so that the Word [of God] may have free course ”

Luther also sought to rid the service of every trace of false teaching, which for him centered in the Canon of the Mass, a collection of prayers and responses surrounding Christ’s words of institution. Luther rejected the implicit teaching that the Mass was a sacrifice the priest offered to God. For the Canon, he reserved some of his choicest criticism, calling it, “that abominable concoction drawn from everyone’s sewer and cesspool.”

Luther nonetheless understood that hasty reform would only make matters worse. In his first revised liturgy of 1523 (An Order of Mass and Communion for the Church at Wittenberg), Luther said, “I have been hesitant and fearful, partly because of the weak in faith, who cannot suddenly exchange an old and accustomed order of worship for a new and unusual one.” Indeed, the six-year gap between the start of the Reformation and his first liturgical reforms demonstrates Luther’s caution.

Luther’s Order of Mass was itself a conservative reform effort. Certainly, the Canon of the Mass was out, replaced with instructions that Christ’s words of institution be chanted loudly. And all communicants would receive not only the body but also the blood of Christ in the sacrament. Still, though the singing of German hymns was encouraged, Latin remained the principal language.

The shift from Latin to German was also delayed because not many hymns or portions of the liturgy had been translated into German. Luther sounded the call for qualified poets and musicians to produce German hymns and liturgies that faithfully proclaimed God’s Word. Near the end of 1523, Luther wrote to Georg Spalatin, pastor to the prince of Saxony, urging him to write German hymns based on the Psalms. His straightforward advice: use the simplest and most common words, preserve the pure teaching of God’s Word, and keep the meaning as close to the psalm as possible.

By 1526, enough materials had been produced to enable Luther to prepare a service entirely in German. This German Mass followed the historic structure of the liturgy. Though Luther inserted German hymns to replace Latin, he insisted that Latin services continue to be offered on occasion. In fact, his ideal would have been to conduct services not only in German and Latin, but also in the biblical languages of Greek and Hebrew!

Hymn Writer

Between the publication of his 1523 and 1526 services, Luther began writing hymns. Though he had expressed doubts about his ability, he was not one to wait around indefinitely. Besides, Thomas Munzer, the radical German reformer, was already producing German services and hymns. In order to protect his people from Munzer’s teachings, Luther decided to provide hymns of his own.

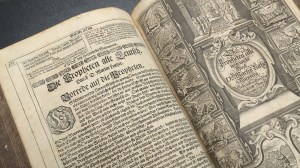

During the final months of 1523 and the beginning of 1524, Luther produced more than twenty hymns—more than half his total output. Four of these appeared in January 1524 in the first Lutheran hymnal (known as the “Hymnal of Eight,” since it contained eight hymns).

By the summer of 1524, two other hymnals appeared in the neighboring town of Erfurt; each contained about two dozen hymns, eighteen of them by Luther. In 1524, the first hymnal prepared under Luther’s auspices also went to press. Unlike modern hymnals, it was actually a choir book with multivoice settings. Of its thirty-eight hymns, twenty-four were by Luther.

Hymnals proliferated so rapidly that many of them published hymns by Luther without permission. Though Luther did not have the modern-day concern of copyright infringement, he didn’t want others making “improvements” to his hymns, lest the pure teaching of God’s Word be adulterated.

Luther wrote a variety of hymns. His first, more of a ballad, came following the deaths of the first two Lutheran martyrs (in Brussels on July 1,1523). Luther used this hymn to counter rumors that the two men had recanted before they died. Luther sings that though enemies can spread their lies, “We thank our God therefore, his Word has reappeared.”

Luther’s other hymns were intended for church services and for devotions at home. In 1524, Luther wrote six of his seven hymns based on psalms. His final psalm hymn, “A Mighty Fortress,” was written about three years later, when Luther was undergoing severe trials. This hymn exhibits a much freer style and is only loosely connected to the text of Psalm 46. Yet “A Mighty Fortress” reflects both Luther’s struggles and his utter confidence in God: “Though devils all the world should fill, / All eager to devour us, / We tremble not, we fear no ill, / They shall not overpower us.”

Luther also wrote hymns for portions of the liturgy and for all the seasons of the church year. To teach the catechism, he wrote two hymns on the Ten Commandments, a hymn for the Apostles’ Creed, one for the Lord’s Prayer, and others for baptism and the Lord’s Supper. Through these hymns, Luther demonstrated his ongoing desire to teach the faith, especially to children.

Martin Luther forged a new hymnody and church music that continues to express the message he proclaimed.

Paul J. Grime is pastor of St. Paul's Lutheran Church in West Allis, Wisconsin, and a doctoral candidate at Marquette University.

Copyright © by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.