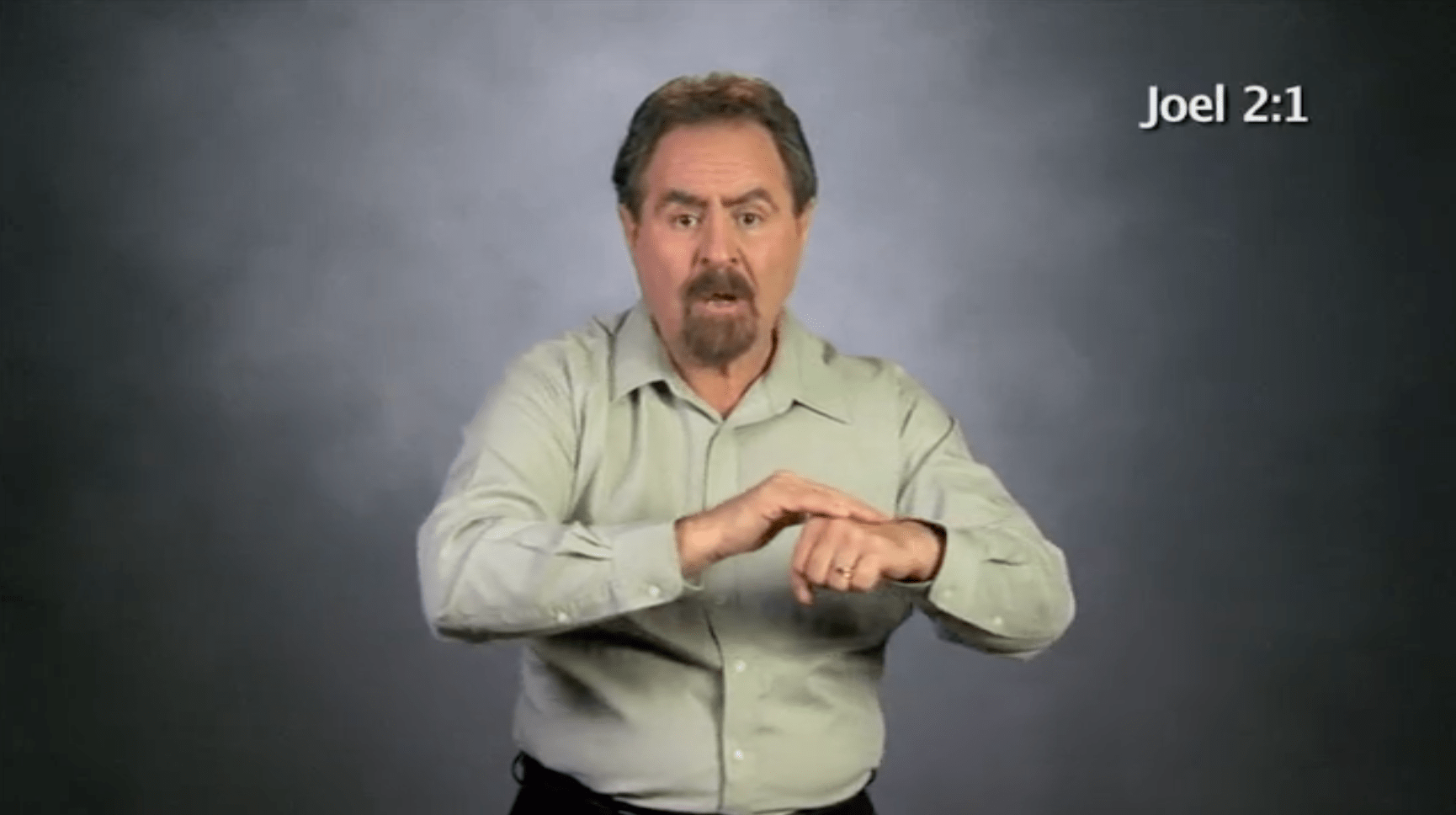

The completion of the first sign language Bible translated from the original languages prompted cheers and celebrations in the fall of 2020.

It took nearly four decades for more than 50 translators to finish the American Sign Language Version (ASLV), and the project started by Deaf Missions received crucial support from the Deaf Bible Society, DOOR International, Deaf Harbor, the American Bible Society, Wycliffe Bible Translators, Seed Company, and Pioneer Bible Translators.

But for the deaf, it’s one down, more than 400 to go.

“Still only one sign language of the over 400 has a complete Bible,” said J. R. Bucklew, the founder and former president of the Deaf Bible Society, who now works as director of major gifts at Pioneer Bible Translators. “And still, no other sign language outside of the American Sign Language has a full New Testament. There’s a lot of work ahead of us.”

Bucklew doesn’t diminish the significance of the completion of the ASLV. As a hearing person born to deaf parents, he sees the translation as a major historic event. And as an advocate for sign language Bible translation, he sees the ASLV as the “great accelerator” that is helping build the momentum necessary for the translation work that remains to be done.

IllumiNations, an alliance of 11 Bible translation organizations, has set a goal of rendering Scripture in every known language by 2033. There are, according to the group, about 7,000 known languages in the world, and roughly more than half have little or no Bible. While people may access Scripture by learning English, Spanish, or a dominant trade language, the evangelical organizations believe everyone should have equal access in their “heart language.”

Including sign language.

Many hearing people think sign language is only an alternate rendering of vocabulary—similar to how Braille reproduces written text in a code of raised dots. Sign language, however, has its own vocabulary and its own grammar, and linguists consider it a distinct language.

The leadership of illumiNations has added more than 400 sign languages to its list of thousands needed Bible translations, despite already facing the challenge of meeting that 2033 goal.

If sign languages were left off that list, the translation alliance would have missed a lot of deaf people throughout the world. No good data is available on how many people know each of the hundreds of sign languages. But reportedly, more than half a million each sign in Indo-Pakistani, Indonesian, Russian, Brazilian, and Spanish, and more than 100,000 use another half-dozen sign languages.

The ASLV Bible made the entirety of Scripture accessible to the 3.5 million people for whom ASLV is their heart language. Translator Jose Abenchuchan does not need to look far to understand the impact of his work. On a shelf in his home, he keeps a copy of the Bible his deaf mother used before she died.

The cover is missing, from extensive use. The pages inside are marked with the copious notes she made as she struggled to understand written English.

“I cherish it because it helps me remember the fight my mom had,” Abenchuchan, who is also deaf, signed to CT through an interpreter. “And that’s why I’m involved in Bible translation now.”

Abenchuchan started working on the ASLV in 1995 and stayed through to the completion, helping with more than 30 books of the Bible. He currently works as the coordinator of deaf field projects for Pioneer.

“You couldn't ask the Spanish people to read an English Bible, right? It would be like reading a foreign language,” he signed. “That’s why the ASLV was so significant, because it’s in our heart language. And it’s changed so many lives.”

IllumiNations describes the lack of Scripture as “Bible poverty.” Erle Deira, director of partnerships at American Bible Society, says that’s a good way to think about it.

To understand the significance of the ASLV, Deira said, “you have to create an image of standing in front of a river, and on the other side of the river, you have all the food that a population would need to nourish itself and live well. But there is no bridge to cross that river.”

Building a bridge won’t be easy, though. The first problem is money. Translating the ASLV—which required video production, in addition to humans who knew the biblical languages well enough to translate them—cost about $195 per verse. The project would have taken an additional 13 years without support from all the Bible societies, translation organizations, and Christian groups coming alongside Deaf Missions.

Translating 400 more sign language Bibles could cost an estimated $350 million, Bucklew said. Christian groups like Passion have already started raising money for the work.

Another challenge is finding the multilingual deaf people who can translate the Scripture from the original languages or from American Sign Language. Many deaf people are denied any education and only a fraction of those who receive an education are taught sign language. This is partly due to the fact that hearing parents don’t know how critical sign language can be to a deaf child and worry the skill will separate them from society.

Tanya Polstra, executive director of Silent Blessings Deaf Ministries, said she understands that concern. Most hearing adults don’t know a deaf person, and if they do, the first one they met was their own child. About 90 percent of deaf people are born to hearing parents.

“God has chosen that family to learn about deaf culture and language so that we can all come together to be a body of Christ, not to be separated,” Polstra, who has been deaf since age three, signed through an interpreter.

Sign language Bibles may encourage more people to teach deaf children to sign, and Polstra hopes it will also help deaf people embrace their identity in Christ.

Some deaf people, she said, have been hesitant to turn to the ASLV Bible or the kinds of resources that Silent Blessings Deaf Ministries offers.

“Because they haven’t owned their identity yet,” she said. “Right now, they’re still questioning, ‘Why am I deaf? Why am I suffering in this world?’ Their struggle to be involved in the church, the neglect—maybe they’re wanting to be involved in the church, and people say no because they can’t communicate. So, they associate God as a hearing God.”

There may be many other challenges as well, but the time to start meeting them is now, Bucklew said.

He is encouraged, though, that it’s no longer just deaf ministries working on the project. There is a lot of support, and Bible translation agencies and societies are now including sign languages when they strategize to give the whole world Scripture.

Deaf ministries are increasingly cooperating, and more deaf leaders are emerging within the Bible translation movement and becoming part of the problem-solving processes, according to Bucklew.

He’s hesitant to project precise dates, but Bucklew expects the next two completed translations will be for Colombian and Japanese sign languages.

That will be three down, more than 400 to go.

But Christians are laying aside “logos and egos,” Bucklew said, and the translations are underway.

“Through a bunch of imperfect people and imperfect institutions,” he said, “a holy God is doing a perfect work.”