Just beyond the still-under-construction ring road on the outer edge of Erbil, a group interview turns into a mutiny.

“You already understand why we are here,” says one of the 15 displaced Christians and Muslims who have gathered at a World Vision food distribution site in the capital of Iraq’s autonomous Kurdish region. “Everyone in America should know about our crisis by now: ISIS.”

This group is weary of telling NGOs and journalists why they fled their homes, and how hard and fragile life is among Erbil’s abandoned buildings.

They are especially weary because this will be their second winter of displacement. Meanwhile, food aid has decreased from $25 to $16 to now $10 per month. Most refuse to give interviews, despite the fact that their stories could spur Westerners to send more aid. If their current visitors are not there to increase food vouchers, then, they say, everyone is wasting their time.

Steve Jeter / World Vision

Steve Jeter / World VisionSome in the group fidget with 11 oz. bottles of water bearing blue caps and the word life spelled in red. The i is an upside-down exclamation point, a marketer’s attempt at fun in a sad setting.

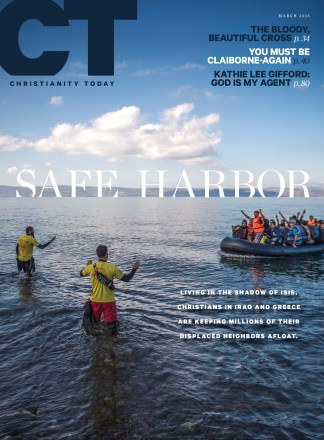

But such a mark fittingly punctuates the refugee crisis. The numbers—1 million refugees entering Europe by the end of 2015—surpassed comprehension long ago. The question is whether they have now also surpassed compassion.

The world now has more displaced people than during World War II. Beyond Europe, another 2.5 million refugees are in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey, while 4.5 million people remain displaced within Syria and Iraq, where ISIS is most active.

As winter approached, Christianity Today traveled to Iraq and Greece to witness how Christian leaders are working along the “refugee highway” that now stretches from the Middle East to Europe and North America. The situation is so complicated, and the risks so high, that leaders are torn between two aid strategies: should they help Christians and other minorities stay in their historic homelands, or should they help them journey to safer Western democracies?

But Kurdish and Greek evangelical leaders agree on one thing: hope remains, because they see God at work all along the highway.

Steve Jeter / World Vision

Steve Jeter / World Vision‘Thank You, ISIS’

From his front steps, Hadi Ali has a great view of the winding ravine where many flock during Nowruz (a New Year celebration) to vacation and picnic alongside the river that descends from Lake Dukan, one of the largest lakes in Kurdistan. But Ali wishes he still lived 300 miles from here. He is one of hundreds of internally displaced persons now living in a jumble of unfinished homes on the slopes of the rugged red mountains that tower above the river.

Steve Jeter / World Vision

Steve Jeter / World VisionIn the shadow of a pale yellow mosque that sits atop the hillside community, Ali, 43, skirts pomegranate skins as he climbs the steps of an unfinished, concrete building. He has lived here with his family of 9 for the past 15 months. His wife and children, ranging from ages 5 to 18, fled from south of Baghdad after they were threatened at gunpoint.

“They took our homes and our money,” he tells CT. “Everything is gone. We don’t know when we will go back.”

Ali, once a school bus driver, sold his bus to relocate his family. Now he’s a day laborer, working on the three-story building next door that is even more unfinished than his own temporary dwelling. “I always think of going back home once peace comes. I wish it were tomorrow. But we don’t know the future. I am waiting for God.”

The crisis has gone on for longer than anybody anticipated—nearly five years now for many families. Almost all of the displaced women whom CT interviewed across eight refugee camps have given birth to children since fleeing.

“We support each other,” says the chief of Garmawa, a 250-year-old Christian town only 40 minutes from Mosul. Ever since ISIS seized Iraq’s second-largest city in June 2014, the nearby town of 70 families has shared its land with about 500 mostly Muslim families. “It is part of our faith that we host them,” says the chief. However, Garmawa residents expected to play host for two months. “This is the second winter,” he says. “We did not dream of this.”

Steve Jeter / World Vision

Steve Jeter / World VisionChristians have faced significant and well-publicized persecution (notably in Mosul and other Nineveh Plains cities). Christian leaders told CT that other minorities such as the Yazidis, an ancient religious group, have suffered even worse. Thus, many churches are aiding more non-Christians than fellow believers.

In a UN camp in Khanke, seven Yazidi children tussle over the UNICEF-issued teal backpack found in almost every refugee dwelling and arrange its contents on the floor. It holds not school supplies but photos of their deceased older sister, Almas, killed when ISIS came to their hometown of Sinjar.

Jeremy Weber

Jeremy WeberTheir four-month-old sister, born in this room of concrete walls and a tarp roof, is named in her honor. Their mother, Wadkha, says the memory makes it too painful to return to Sinjar, which was liberated from ISIS while CT was in Iraq. “When I make bread, I think of my daughter and weep.”

Many refugees no longer hope to return home. “The Christians are tired here,” says Ashty Alisha, chairman of the Evangelical Alliance in Kurdistan. At his most recent church service, a member explained how he plans to leave with his family because they have no money for rent or food; all they have is the memory of their son killed by ISIS. Alisha says, “I am not encouraging people to go. But I can’t tell people to stay.”

Father Daniel is more blunt. “The Middle East is lost for Christians,” says the 25-year-old priest at Mar Elia Church, which hosts 570 displaced believers on its triangular compound in Ankawa, Erbil’s Christian district. He just finished leading a service in Aramaic; Mar Elia is one of the few churches that preserve the language Jesus spoke. But Daniel says he would be fine if one day he had no flock to shepherd because they had all left for Europe or the United States.

“We should consider the lives and souls of these people,” he says. “It’s not just about the Christian history here. We don’t want them to live as victims.” A newlywed resident of the camp concurs: “This is truly a holy land here for us. But it is no longer a heartland.”

Steve Jeter / World Vision

Steve Jeter / World VisionBy contrast, Abu Karam is likely one of the only displaced Iraqi Christians to ever turn down a visa to the West. The 66-year-old Mosul pastor became a UN refugee in Jordan and obtained a visa to Canada. But then, he says, God told him in a vision to go back to Iraq and serve the church. He declined the visa and returned to Mosul until ISIS arrived.

At the Christian and Missionary Alliance church in Ankawa, Karam now serves displaced Christians from a range of historic and newer denominations. He encourages them all to stay in Iraq. “Jesus tells us it won’t be easy to continue our religion. But he says, ‘No matter what happens to you, I win, so you will win,’ ” says Karam. “Ever since the third century, this has been our Christianity: one of suffering. If we live an easy life, what is our message?”

Notable efforts to help Christians stay include an evangelical church that rents a five-story building in Erbil for 170 people displaced from Qaraqosh. The Chaldean archbishop of Erbil, Bashar Warda, is trying to build a new Catholic university. (He explains: “How will they stay unless we show them that we are going to stay?”) On the “go” side, a group from Slovakia—visiting Mar Elia at the same time as CT—brokered a deal to relocate 149 Christians to their Eastern European nation by Christmas.

“It is not a zero-sum game of stay or go. We can help people stay safer and go safer,” says Jeremy Courtney, director of the Iraq-based Preemptive Love Coalition. “But if we are serious about helping Christians stay, we have to love Muslims more than we hate and fear Islam. We do bad for Christians if we don’t do good for their neighbors.”

Steve Jeter / World Vision

Steve Jeter / World VisionOne of the silver linings of the crisis is that most of Iraq’s evangelical churches are now overflowing with displaced Christians. They more than make up for the families that emigrated to the West after the United States invaded Iraq 12 years ago. “God is using ISIS to shake the church,” says a leader in Erbil who requested anonymity. “Christians who were nominal are now saying, ‘We need to be the church.’ ”

Likewise, many pastors told CT the crisis presents an unprecedented opportunity for evangelism. “I’ve been here 20 years and shared the gospel with two people; one accepted, one did not,” said a long-term missionary from Egypt who also requested anonymity. “These days, we can reach 2,000 people in one day. This is the time to be here, otherwise we’ll lose the opportunity. I’ve heard many people say, ‘Thank you, ISIS,’ because they lost everything but have new life in Jesus.”

As many churches have become de facto refugee camps, cramming as many Christian families onto their properties as possible, the mixing of different denominations has produced what Pope Francis terms an “ecumenism of blood.”

“Before ISIS came, we were divided. We thought we were the best Christians, and we could do everything on our own,” says Daniel. “God does things for a purpose. He combined the churches together to handle the situation as one hand.

“Unfortunately, it was ISIS that united us. We can send a message to all the Christians around the world: Don’t wait for bad things to unite you; unite now, under the name of Jesus Christ.”

Jeremy Weber

Jeremy WeberParalyzed by Paris

On CT’s last day in Iraq, global sentiment toward refugees began shifting dramatically. Coordinated ISIS attacks killed 130 in Paris. Soon, the main emblem of the refugee crisis—the small body of a drowned Syrian three-year-old on a beach—was replaced by the specter of sleeper terrorists.

More than half of US governors announced bans on refugees resettling in their states (most from Syria are Muslims, while overall almost half are Christians). Polls suggested that many evangelicals supported the bans; only one-third of white evangelical Protestants told the Pew Research Center they favored the United States accepting more refugees—and that was prior to Paris. After the attacks, LifeWay Research found that 48 percent of self-identified evangelical pastors agreed there was “a sense of fear” within their congregation about refugees coming to America.

Steve Jeter / World Vision

Steve Jeter / World VisionBut a month after Paris, one prominent gathering told a different story about evangelical attitudes. On the campus of Wheaton College, more than 120 leaders representing major denominations and ministries gathered to discuss how US churches could best apply the Great Commandment and the Great Commission to the situation, and not repeat the mistakes of what speakers labeled a tardy response to the HIV/AIDS crisis.

Conference organizers had expected only one-fourth as many people to come, but the room overflowed. There, leaders took turns addressing the crowd. Wheaton president Philip Ryken said it was “hard to imagine a more important topic to be talking about a compassionate, Christ-centered response to right now.” Southern Baptist International Mission Board president David Platt used Bible passages to exhort evangelicals to “act justly, love sacrificially, and hope confidently,” given that God remains sovereign over the refugee crisis.

World Vision president Richard Stearns explained how, if the crisis were taking place proportionally in the States, “everyone west of Ohio would have to flee their homes.” He described feeling “ashamed by the hateful rhetoric” from politicians, media, and some church leaders. “They’ve taken this terrible tragedy and somehow made it about us,” he said. “We have an opportunity on the world stage to show what we stand for: not fear, but grace.”

World Relief president Stephan Bauman said that while “this is a time of lament” as refugee resettlement groups receive criticism, his ministry has seen “more volunteers coming out from churches to help than ever” in its 35 years. “Not all Americans will be in favor,” he said. “But as they understand that facts are our friends, and theology is a mandate, more will see we don’t have to have security and compassion be mutually exclusive.” (Two-thirds of evangelical pastors told LifeWay they agree.)

Steve Jeter / World Vision

Steve Jeter / World VisionPrior to Paris, three-quarters of self-identified “committed Christians” in America said they were willing to help Syrian refugees, according to an Ipsos poll sponsored by World Vision. However, only 44 percent had already done so.

Of the one-quarter of committed Christians who were not willing to help, 34 percent said it was because they feared that refugees were potential terrorists, while 24 percent felt the problem was too big for them to make a difference.

Such findings were corroborated at Wheaton, where leaders took a straw poll to identify the main obstacles to mobilizing American evangelicals on refugee care. Only one word received a unanimous vote: fear. Church leaders agreed that they needed better information to circulate in better ways.

Few evangelical churches are currently caring for refugees internationally (18%) or locally (8%). Another 8 percent desire to get involved. But more than two-thirds of churches have not discussed it.

LifeWay also found that only 1 in 3 evangelical pastors have addressed the refugee crisis from the pulpit. A prior survey found that only 2 percent of evangelicals get their information on international migration to America from their local church, while 12 percent cited the Bible. The two combined were fewer than those who rely on the media. “Most evangelical Christians are not thinking as Christians on the issue,” said Matthew Soerens, World Relief’s church training specialist. “Most see newcomers as a threat or a burden. Only 4 in 10 see a gospel opportunity.”

“We are being countercultural,” said co-convener Ed Stetzer, director of LifeWay Research. “The mood of many of our constituents is against refugees. But when we respond in an environment of fear with faith, we win an audience for the gospel.”

Steve Jeter / World Vision

Steve Jeter / World VisionGiving as Much as They Can

More than 80 percent of refugees enter Europe by crossing the Aegean Sea from Turkey into Greece, due to its many islands (like Lesbos) and thus porous border. Most pass through Athens en route to Germany, Sweden, and other popular refuges.

Greek evangelicals were actually leading refugee ministries decades before little Alan Kurdi—dressed in a red T-shirt, blue shorts, and Velcro sneakers—washed up on a Turkish beach and galvanized the world’s attention on Syria and Iraq. And they remain at the forefront, even as their own nation weathers a 25 percent unemployment rate and a debt crisis that nearly brought down the Eurozone.

At a coffee shop in Athens, a family clasps their cups at a high street-side table while their three-year-old son plays with a yellow toy crane among a pile of backpacks. He is bundled up for the cold, but he also wears a blue life jacket. His younger sister wears a red one.

Here on the blocks around Piraeus, the main port of Athens, refugees who survived the dangerous crossing from Turkey to Lesbos (more than 800 drowned in 2015) outnumber Greeks 4 to 1. Dozens walk past closed shops to board a white double-decker bus bearing a Greek Islands ad of two smiling children lounging on a sunny beach. A blue bus soon pulls up, followed by a yellow one as the white bus prepares to depart.

Jeremy Weber

Jeremy WeberIt is likely headed to Victoria Square, a plaza lined with restaurant patios and trees decked with strands of gold Christmas lights. As the sun sets on Saturday night, almost 50 people wait in line at a food truck. But this is no gourmet hipster meal. They are all refugees, waiting here for the buses that will take them to Greece’s northern border with Macedonia, then on through the Balkans to Germany. The truck belongs to Plision, a ministry where Greek evangelicals unite with other groups to offer aid. Tonight it is passing out 500 black bowls filled with beef, rice, and beans made by church volunteers.

Shortly after, Plision’s leader, Christos Nakis, sits at the plastic-covered Communion table of his charismatic church, fittingly located next to Athens’s central market where rows of vendors sell produce and meat. He explains how 10 teams from evangelical churches help feed about 1,700 migrants a day across Athens’s three refugee camps.

One month ago, leaders of all of Greece’s evangelical churches gathered with Nakis to agree to help non-Christians and Christians alike. “We think our mission as people of God is to help everybody the same. After all, God sends rain the same on the good and the bad,” says Nakis, referring to Matthew 5:45.

“The refugee crisis is both new and not new,” says Giotis Kantartzis, senior pastor of one of Greece’s largest evangelical churches. “Greece has been receiving refugees for a long time. What is different is the intensity of it.”

What was once 3,000 migrants per week has become 3,000 per day. So the Greek Evangelical Alliance gathered all the churches and ministries that represent the officially Orthodox nation’s 40,000 evangelicals.

“For the very first time in our history, we were able to sit down and coordinate our efforts,” says Kantartzis. “Some wanted to do evangelism and give out Bibles. Others said, ‘No, let’s just have a Christian aroma.’ [This collaboration] is a new thing. And it is a good thing.”

Jeremy Weber

Jeremy WeberCT rides along as a church volunteer transports dinner to Galatsi Hall, once the Olympic stadium where Greece hosted the Summer Games in 2004. It lay in modern ruins until the government made it the largest refugee camp in late 2015.

Most Galatsi refugees are from Afghanistan. They spend a few days waiting for money from relatives in the West to arrive before continuing on. Most Syrians and Iraqis, including the Christians, have enough money to pass through Athens the same day, leaders explain.

Jeremy Weber

Jeremy WeberMoinos Eleftheriou, 53, is tall with a mop of wiry hair and the energy to match in his role as camp leader. Galatsi provides food, bedding, clothing, medical supplies, English lessons, art therapy—even a “goodbye goodie bag” for those going farther up and farther into Europe once they obtain a bus ticket out of Athens. “We have to help them,” says Eleftheriou. “They are our neighbors. They are not animals; they are human beings.” The cavernous rooms that hosted the world’s best gymnasts and table tennis players now house mostly Afghan women and children clustered on blankets. A lucky few have camping tents for privacy.

“We give them as much as we can,” explains Eleftheriou. The parting gift is a grocery bag full of “things they like”: juice, milk, biscuits, honey, tuna fish, toilet paper. The facility even has an elderly woman pushing a shopping cart around giving out sweets. “We do the small things to make them smile.”

Jeremy Weber

Jeremy WeberJust 45 days old, the camp has already hosted 10,000 refugees. One main wall showcases the drawings of the 3,000 Afghan children who have passed through Galatsi. “Some of them are very sad. We don’t put those here,” says Eleftheriou.

Back in his office, he pulls out a drawing of a girl’s family in a boat. Overhead, the sun is shedding tears. Earlier, walking through the middle of the gymnastics hall turned dormitory, a woman in a black robe and pink headscarf stood up from her family’s three blankets and half bowed as he passed. Her two-year-old daughter, as well as her sister and seven-year-old niece, drowned when her family crossed the sea. When he first asked what the family needed, the mother replied tearfully, “The only thing I need is a stone with my daughter’s name on it for the graveyard.” Eleftheriou told her, “I will do this for you.”

Jeremy Weber

Jeremy WeberGreek evangelicals recognize that, living in one of the world’s most “Christian” countries (legally and culturally), they are the first believers many refugees from Afghanistan and other Muslim-majority nations encounter. “I can’t show them a film of Jesus’ life,” one leader told CT. “But bit by bit, it will all happen.” (As a Plision driver puts it, “If they see Jesus in our face, it is enough.”) A child’s poem on the Galatsi wall of drawings suggests success: “I was in Iran. I saw a lot of Muslims but I didn’t see [godly people]. When I came to Greece, I saw a lot of non-Muslims. But I saw [godly people].”

On the question of whether Christian refugees should remain in the Middle East or leave for the West, Kantartzis quickly shoots down the question as not worth pondering. (This is noteworthy, given an Athens tourism campaign coins the term “philosofa” for “the Athenian habit of lounging around and philosophizing.”) “It’s the wrong question. These people came; they left already,” he said. “The question is a kind of avoidance; an alibi to dodge the responsibility in front of us.

“It is a wakeup call,” he says. “Are we ready as the church to show who we are and what we believe?”

Steve Jeter / World Vision

Steve Jeter / World VisionArab Spring from Above

Surveying Athens from its tallest peak, Fotis Romeos, general secretary of the Greek Evangelical Alliance, gestures to the New Testament sites nestled among the modern below. He believes American evangelicals can learn from their brothers and sisters at one of the world’s major crossroads.

“Refugee ministry is not new for us. What is new is the pace.” Previously, most refugees would stay in Greece for six months to one year to acquire their legal papers. Now they stay two or three days before moving on.

“We once had a chance to get to know them and share the gospel,” says Romeos. No longer. So churches now focus on “helping them feel human” by offering showers, children’s games, cell phone recharging—even free wifi. “Refugees are people, not a caste. We can serve them in what they need right now,” he says. “We have the first opportunity to engage them with the best elements of our faith and our culture.

“We trust that the Lord will complete his work in other countries through the evangelicals there,” says Romeos. “We look at these people as long-term residents of Europe, and we try to focus on being the best hosts at the entrance.”

Given that Greek evangelicals are few in number, with their resources already stretched thin by their country’s financial crisis, Romeos wants strategic, long-term partnerships with evangelicals in America and other nations. “It is a dilemma of short-term fireworks or long-term fire,” he says. “We don’t want to light the fireworks show; we want to fuel the long-term kingdom of God.”

Since the Syrian and Iraqi families slowly reaching Western shores represent only 5 percent of the refugee crisis, church leaders in Iraq and Greece encourage US evangelicals to take their cues from those closer to the action.

“Why are you Christian brothers in the West afraid? We are here on the front lines and are not afraid,” said an Iraqi pastor appearing via video at the Wheaton leader summit. “We believe in an Arabic spring, but not this Arab Spring. We believe in one that comes from above. And we know that spring comes after winter.”

Jeremy Weber is senior news editor of Christianity Today. To get involved with the refugee crisis, visit wewelcomerefugees.com and refugeehighway.net.