Conversion. Revival. Biblical authority. A warm-hearted faith touching all areas of personal and social life. Billy Graham believes in these things. So did Billy Sunday, D. L. Moody, and Charles Finney. And so do countless others today who would place themselves in the Protestant family tree most often termed “evangelical.”

If you had to put someone at the very root of this tree, who would it be?

For my money, one of the two top contenders for the title “Evangelical Patriarch” is Jonathan Edwards. (The other is John Wesley.)

Edwards’s preaching—aimed at breaking down and converting a group of Yankees who saw religion as more or less a do-it-yourself project—helped spark the first flames of the Great Awakening, the “mother” of all revivals on this side of the Atlantic.

The Bible was his constant guide as he reworked the grand theological tradition of Puritanism for an Enlightened age and as he taught a religion not just of doctrines but also of whole-hearted love for God.

He expected and encouraged a thorough moral reformation in every person truly converted as a result of the revivals of his day, and his teachings inspired a reformation in American education and society.

But his strongest claim to the title “father of evangelicalism” comes from the transatlantic influence of a single book, A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God.

Mark Noll tells the story compellingly in a forthcoming book on the emergence of evangelicalism during the eighteenth century to be published by InterVarsity Press.

In November of 1734, Edwards, concerned by what he saw as a spreading tendency among Connecticut River Valley Christians to rely on their own abilities in seeking salvation from God, preached a two-sermon series on “Justification by Faith Alone.”

In response came what Edwards later called, in grateful awe, a “surprising work of God.” The people in Northampton and the surrounding area were, he said, “seized with a deep concern about their eternal salvation; all the talk in all companies, and upon occasions was upon the things of religion, and no other talk was anywhere relished; and scarcely a single person in the whole town was left unconcerned about the great things of the eternal world. …

“Those … that had the greatest conceit of their own reason, the highest families in the town, and the oldest persons in the town, and many little children were affected remarkably; no one family that I know of, and scarcely a person, has been exempt.”

Edwards organized small groups to encourage those experiencing such concern, and soon hundreds were “brought to a lively sense of the excellency of Jesus Christ and his sufficiency and willingness to save sinners, and to be much weaned in their affections from the world.” The revival spilled over into 1735, touching some 25 Massachusetts and Connecticut communities before its intensity began to wane that spring.

Even as the Northampton revival was abating, a member of John and Charles Wesley’s Oxford “Holy Club,” the evangelist George Whitefield, was experiencing his own deep conviction and conversion. Along with the Wesley brothers and others, Whitefield soon witnessed in England similar scenes of heightened religious concern and widespread conversion—events culminating in that country’s “evangelical awakening.”

Although the events in Connecticut and Massachusetts transformed the communal life of many towns in that area, they might have remained only local lore but for a request made by a Boston minister, Benjamin Colman, for a report. Edwards wrote a short response, Colman passed it on to friends in London, and soon the British were writing back, asking eagerly for more details.

Two years later, an enlarged and edited version of Edwards’s report reached a London printer (one of the editors was the renowned British hymn-writer Isaac Watts), who published it as the Faithful Narrative. Soon the book was capturing the imaginations of thousands (including John Wesley and the Welsh evangelist Howell Harris, both of whom devoured Edwards’s revival account and recorded their impressions in their journals).

From that day to this, it has never gone out of print.

Why?

What the Narrative provided to the dynamic but scattered transatlantic revival of the mid-1700s was a pattern. As Christian leaders on both sides of the ocean celebrated, fostered, and organized the revival that was bringing new life to pew-sitters and salvation to the unchurched, they found in Edwards’s book a sort of evangelical Baedeker’s, Hoyle’s, and Joy of Cooking rolled into one. The Faithful Narrative was not merely an inspirational account, but a complete map, guidebook, and how-to manual covering the preparation, onset, maintenance, regulation, dangers, and effects of revival—all, of course, with the understanding that the work of conversion was finally God’s alone.

In Noll’s words, Edwards provided, at the crucial moment of evangelicalism’s birth, “a template for how conversions would proceed and for how they could effect social renewal.” Everywhere, “evangelical preaching was inspiring the formation of local, predominately lay-led societies for the provision of spiritual nurture and community among those who were, or who would be, converted.” The leaders of these societies held in one hand, as often as not, a copy of Edwards’s little book.

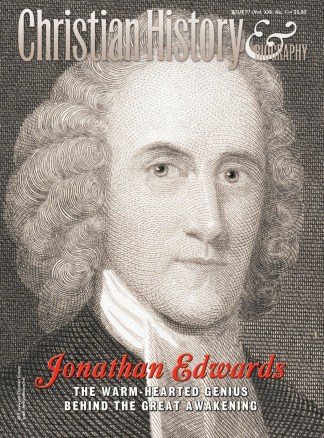

So if you identify with the tradition of evangelicalism that emerged out of the awakenings of the eighteenth century, take another look at the man on the cover of this magazine. Then practice saying, “Hi, dad!”

Copyright © 2003 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.