In 1964, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote: “I am ready to go to Auschwitz any time, if faced with the alternative of conversion or death.” The prominent Jewish theologian was protesting a reference to the future conversion of the Jews in a Vatican II working document on Catholic-Jewish relations. Both The New York Times and Time magazine picked up on Heschel’s letter, which alienated many of his Christian friends.

That was 1964. This is 2007. Jews still find the subject of conversion extremely painful. For them it is, as Heschel said, tantamount to annihilation. Christian hopes for conversion can be a deal breaker in interfaith friendships.

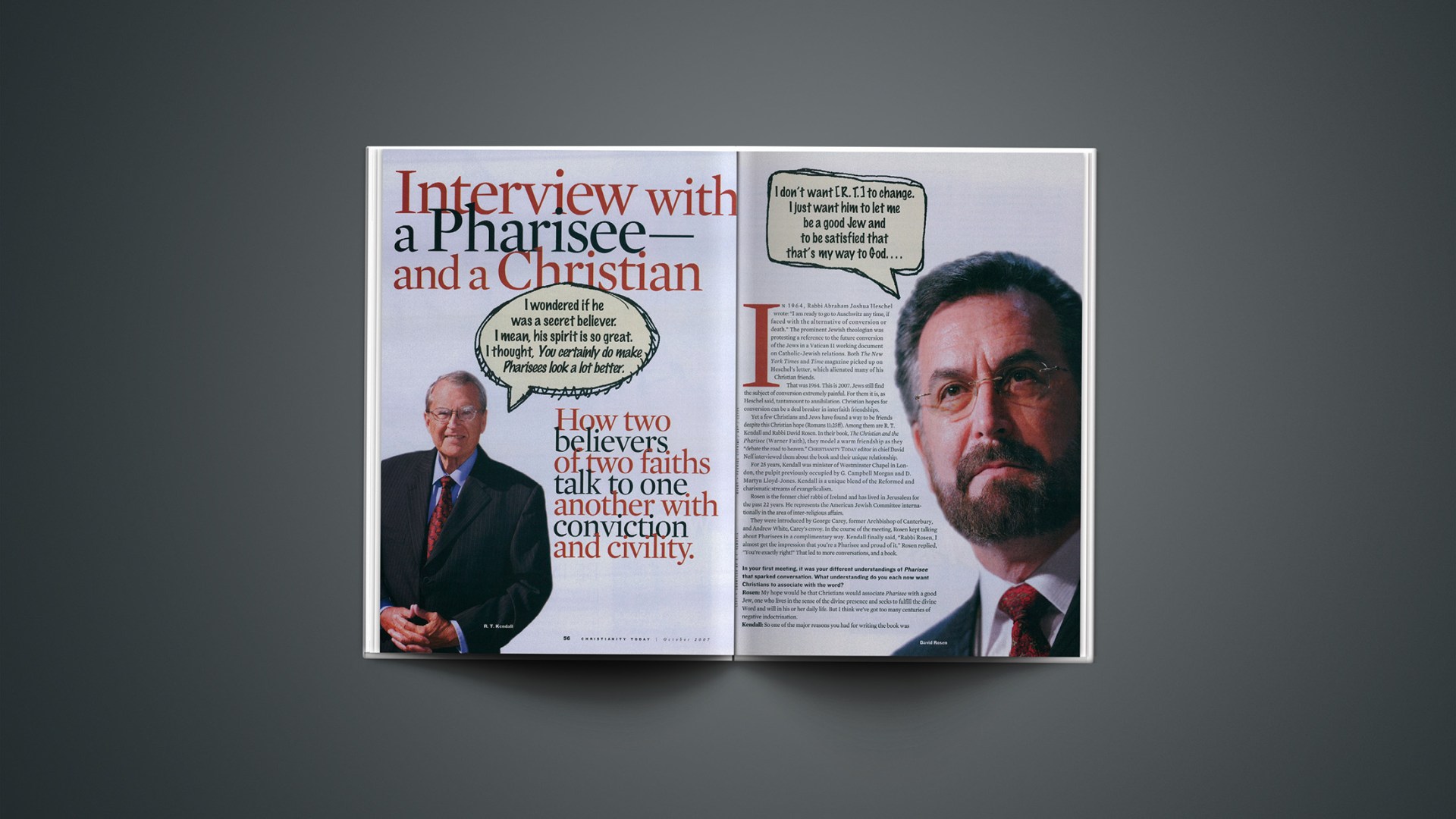

Yet a few Christians and Jews have found a way to be friends despite this Christian hope (Romans 11:25ff). Among them are R. T. Kendall and Rabbi David Rosen. In their book, The Christian and the Pharisee (Warner Faith), they model a warm friendship as they “debate the road to heaven.” Christianity Today editor in chief David Neff interviewed them about the book and their unique relationship.

For 25 years, Kendall was minister of Westminster Chapel in London, the pulpit previously occupied by G. Campbell Morgan and D. Martyn Lloyd-Jones. Kendall is a unique blend of the Reformed and charismatic streams of evangelicalism.

Rosen is the former chief rabbi of Ireland and has lived in Jerusalem for the past 22 years. He represents the American Jewish Committee internationally in the area of inter-religious affairs.

They were introduced by George Carey, former Archbishop of Canterbury, and Andrew White, Carey’s envoy. In the course of the meeting, Rosen kept talking about Pharisees in a complimentary way. Kendall finally said, “Rabbi Rosen, I almost get the impression that you’re a Pharisee and proud of it.” Rosen replied, “You’re exactly right!” That led to more conversations, and a book.

In your first meeting, it was your different understandings of Pharisee that sparked conversation. What understanding do you each now want Christians to associate with the word?

Rosen: My hope would be that Christians would associate Pharisee with a good Jew, one who lives in the sense of the divine presence and seeks to fulfill the divine Word and will in his or her daily life. But I think we’ve got too many centuries of negative indoctrination.

Kendall: So one of the major reasons you had for writing the book was to make Pharisees look a lot better?

Rosen: It was to take away the unfair stigma. The argument between Jesus and some of the Pharisees is a legitimate family dispute. This is like when the ancient prophets condemn the children of Israel. They talk about the bad behavior, but they don’t disassociate themselves from Israel. They see themselves as part of it.

So I believe that Jesus was a Pharisee who knew that there were wonderful Pharisees around, probably the majority, but there were some who were actually desecrating the name, the message, and the tradition they were meant to be the custodians of.

Kendall: When we started the book—don’t laugh—I wondered if he was a secret believer. I mean, his spirit is so great. I thought, You certainly do make Pharisees look a lot better. But then, halfway through the book, when you stopped debating Scripture and started putting forward the rabbinic authorities instead, I said, “Ah, you’re somewhat like the Pharisees after all.”

Jesus said to the Pharisees, “You make the Word of God null and void through your traditions.” And they only quote the authorities; they didn’t want to quote Scripture.

Rosen: I think that Jesus would have understood—as all Jews would have understood—that it is not possible to understand all of the biblical text totally literally. Interpretation is necessary.

As you wrote this book, both of you remained firm in your own traditions. Why is it important in inter-religious dialogue for people to be rock solid in their beliefs?

Rosen: I believe that a real dialogue is most authentic when people are deeply committed to their faith. To say that my truth is my truth does not mean that my truth is the only truth, but it is truth.

Kendall: I don’t see this as only dialogue. I had one sincere desire, and that was to present the gospel to David with the love I feel for him so that the Holy Spirit would arrest him like Saul of Tarsus on the road to Damascus.

Who knows whether God can use a man like this to precipitate the lifting of the blindness described in Romans 11. I know that’s grandiose, but I thought what if, somehow, God got to this wonderful, learned, world-famous man. Of course, I annoyed him a bit along the way, though we stayed friends.

Rosen: Our motives were different. For me, dialogue doesn’t mean, as some people suggest, any kind of relativism. And it certainly doesn’t mean any weakness in one’s own tradition. Communication is a value in and of itself. But I want R. T. to be a good Christian. I don’t want him to change. I just want him to let me be a good Jew and to be satisfied that that’s my way to God and that God is very happy with me living the way I live.

Kendall, as a Reformed Christian, you approach evangelism a little differently than do many Christians.

Kendall: I know that only God does the saving. So I can only pray that the Holy Spirit would do the job. I did all I can do—and I haven’t given up, by the way. I pray for you every day. If I’m right, you will go to hell when you die, and I don’t want that. And so I want to do everything I can. Though you are adamant and lovingly hostile to all that I believe, remember that Saul of Tarsus was as well.

Rosen: I wouldn’t call myself hostile. I just don’t understand what you’re talking about. But there is a history that could naturally lead to hostility. And certainly most Jews probably would be hostile to it.

Kendall: There’s a double blindness upon a Jew. First, 2 Corinthians 4:4 says the god of this world blinds the minds of those who don’t believe—that’s everybody. But when it comes to a Jew, there’s something over and above that. God has given them a spirit of stupor—eyes so they cannot see. But I think the day will come when you will say, “Where have I been? I can see it! It’s so clear to me!”

Rosen: If there is something that I’m not seeing that is of essential importance, then I pray that the Almighty will reveal it to me.

But as I said also in the book, central Christian ideas, such as the concept of Incarnation, completely defy my religious understanding. Moreover, we use common terminology that we understand very differently. The term Messiah, for example. If you mean that Jesus is the individual who will be the wise, human ruler at the time of God’s era of universal peace, then there would be no objection to that on principle. Otherwise, there just doesn’t seem to me to be any logical reason to think that’s the case.

I’d like to know what each of you may have learned from the other.

Kendall: I’ve seen that David has no conviction of sin. He sees himself as basically righteous. The thought of being sinful before God, like Isaiah in chapter 6, is alien to him.

Well, David, what about the concept of sin?

Rosen: With regard to sin, I refer to the verse in Ecclesiastes, and I certainly see myself in that category—”For there is no man righteous in the world who does only good and sinneth not” (Ecc. 7:20). Of course, I’m a sinner like everybody else. But that doesn’t mean I’m inherently a sinner. It means that maybe every day I do something wrong, but that’s because in some manner, I have not managed to live up to the standards I am meant to live up to.

It’s hard for Christians not to think of the apostle Paul’s struggles in Romans 7.

Rosen: The idea which our sages refer to as “the evil inclination” does not necessarily mean there is anything inherently evil in man. There are different attitudes among the rabbis of the Talmud about it. For example, one of them says that if it were not for the evil inclination, a man would not build a house, he would not marry a wife, and he would not earn a living. He refers to the passionate dimension of the human personality that can get out of hand; therefore, it needs to be channeled in the right way. But others look at it in a much more negative way.

Kendall: Paul said in Romans that the problem with Jews is that they’re trying to establish their own righteousness. I see you, David, as the living embodiment of that.

You said in the book you don’t agree that faith is salvific. You even implied there’s not a place for faith in Judaism. Look at Habakkuk: “The just shall live by God’s faithfulness.”

Rosen: It depends on what you mean by faith.

Kendall: Trust, reliance.

Rosen: Total trust and reliance on God. I live in faith daily, my sense of God’s presence. In other words, my confidence and trust in God is total. But the idea that I need to believe in something in order to find the salvation of my soul, that defies my rational comprehension.

Kendall: You see, many of those Pharisees who professed faith in Christ still stumbled at this idea of justification by faith alone. And that’s the offense of the Cross, that my trust in the blood that Jesus shed on the Cross is what gets me righteousness in God’s sight.

Rosen: That I cannot comprehend.

Jews have traditionally been insulted by “replacement theology”—the idea that the body of Christian believers has taken the place of the Jewish people in God’s covenant.

Kendall: Romans says all Israel will be saved. The olive tree in Romans 11 means you, a natural Jew. But I reject replacement theology.

Rosen: So you’re saying, that I, as a Jew, have an eternal destiny; I just at some stage have to open my eyes and be delivered from this blindness.

Kendall: I don’t say that you can do it without the help of the Holy Spirit. But I hold that this blindness that is on Israel will be lifted prior to the Second Coming. Like a stack of dominoes falling all over the world, in New York and Miami Beach as in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, there will be a large-scale lifting of the blindness of Jews. It will be a sovereign work of the Holy Spirit.

Rosen: Replacement theology is a form of anti-Judaism. It says you just basically have no place—other than perhaps with Augustine’s clever argument that the only reason you survive is that your humiliation and homelessness are a testimony to the truth of Christianity.

That attitude, which leads to the teaching of contempt toward the Jews and Judaism, is a direct product of replacement theology. For those that have that theological outlook, R. T.’s avenue is critically important, because it’s a way to redeem themselves from the sin of anti-Judaism.

I would like Christians to [have] an attitude that is reflected more within mainline Protestantism and within the Catholic church, which is to say that there are at least two ways of articulating the covenant—and that these two are complementary. Christianity is part of God’s destiny for humanity, but Jews do not have to relinquish their own particular Jewish worldview in order to be able to be part of God’s design.

Some people say Christians have theology but Jews have halakhah, or religious practice. Is that true?

Rosen: It’s wrong to say there’s no doctrine and no theology in Judaism. However, the essence is the conviction that there’s one God who brought the universe into being and who guides the universe, that his Word is revealed, and that we can therefore know God’s Word through the Torah. Accordingly, the most important thing is for us to understand and to do what God wants us to do.

Kendall: Christianity is basically about a person, Jesus of Nazareth—who was, we believe, the God-man. And it isn’t as much what he taught about loving one another and all of the things people say they admire about Jesus. The heart of Christianity is the person of Jesus, who he was and what he did more than what he said, although we accept what he said as true.

Many Jews have a deeply negative view of Jesus’ followers. What would it take to rehabilitate that view for Jews?

Rosen: That rehabilitation has started to take place. Within the Catholic church, that happened with the Second Vatican Council and Nostra Aetate. After the visit of the Pope to Israel in the year 2000, for the first time Jews really began to understand that there is a change. What would it take? The answer is very simple for a Christian.

Kendall: And that is?

Rosen: And that is love. The more love Christians show Jews, the more they will be able to overcome the tragedies of the abuse of the past in their name.

But that’s very difficult for someone like R. T. to be able to do effectively, because even though he is genuine about demonstrating love on our personal level—I genuinely feel it—from a collective point of view as a religion, if he’s relating to me as someone who’s going to burn in hell, then I can’t really see that as genuine love toward my people and my faith.

I am suggesting to those evangelicals who could hear this, out of your sense of duty to the people from which your Savior came, and out of your sense of responsibility for the terrible abuse that’s been done in your name historically, suspend your proselytizing and allow the Almighty to do whatever the Almighty thinks in his wisdom is the thing to do in his own time.

Kendall: If I have failed you, it is because I haven’t loved you enough. As I re-read what I wrote, I think I was trying to make you see it intellectually. And that isn’t the way a person comes to Christ.

When people in your own communities read the book, what do you hope they will learn?

Rosen: It is very important to educate Christians about Judaism and about why we believe what we believe and how we look at texts. I definitely was less concerned with this book’s significance in the Jewish community. But Jewish readers also see this as an educational text, so that we can get to know one another a little bit more.

Kendall: First, that Christians will pray for David Rosen and all Jews and that Christians will appreciate what Judaism is like today. But then they will also see how much it is still the same as it was in Jesus’ day.

I also wrote it hoping that fundamentalist, premillennialist Christians might see a different perspective. I would like those who are into replacement theology to see another perspective.

But most of all I think I’m hoping that many Christians will give [the book] to Jews so that the Holy Spirit will use what I said. There’s enough in there that God can use to bring many people to the Lord Jesus. And maybe you, David, will have it happen to you. I’m sorry, but I haven’t given up.

Rosen: And you’ll never give up, R. T.; I realize that.

Copyright © 2007 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Christianity Today sister publication Books & Culture ran a five-part series on Jewish-Christian relations in 2000-2001. It also ran companion articles and a series on evangelicalattitudes toward Israel and Palestine.

Other Christianity Today articles on Jews and Christians include:

Kosher Cooperation | Jewish elites broker new relations with evangelicals. (October 1, 2003)

Editor’s Bookshelf: The Church’s Hidden Jewishness | In the Shadow of the Temple illumines Hebrew thinking in a Greek world (Sept. 15, 2003)

Editor’s Bookshelf: ‘Normalizing’ Jewish Believers | How should Christianity’s Jewish heritage change how Gentiles relate to their faith? An interview with Oskar Skarsaune (Sept. 15, 2003)

Christ via Judaism | Lauren Winner’s spiritual journey is an invaluable—and, to some, unsettling—reminder of where we came from (July 7, 2003)

Weblog: Messianic Jews in Canada Lose Appeal to Use Menorah Logo (June 26, 2003)

A Christian Studies Torah | Athol Dickson’s The Gospel According to Moses encourages exploration of Jewish roots (May 14, 2003)

Weblog: Christian Seders Accused of Being Anti-Jewish | We’re waiting for Elijah, not Jesus, say Jews (Apr. 28, 2003)

Do Jews Really Need Jesus? | What evangelicals believe about evangelization of the Jews—and whether the Holocaust makes a difference in that task (Oct. 8, 1990, reposted Aug. 16, 2002)

The Chosen People Puzzle | When it comes to relating to the Jewish people, should we dialogue, cooperate, or evangelize? (Mar 9, 2001)

Is Evangelism Possible Without Targeting? | The founder of Jews for Jesus responds to Rabbi Yechiel Eckstein (Jan. 14, 2000)

Can I Get a Witness? | Southern Baptists rebuff critics of Chicago evangelism plan. (Jan. 14, 2000)

Witnessing vs. Proselytizing | A rabbi’s perspective on evangelism targeting Jews, and his alternative (Dec. 3, 1999)

To the Jew First? | Southern Baptists defend new outreach effort (Nov. 15, 1999)

How Evangelicals Became Israel’s Best Friend | The amazing story of Christian efforts to create and sustain the modern nation of Israel. (Oct. 5, 1998)

The Return of the Jewish Church | In 1967, there were no Messianic Jewish congregations in the world. Today there are 350. Who are these believers? (Sept. 7, 1998)

Mapping the Messianic Jewish World (Sept. 7, 1998)

Did Christianity Cause the Holocaust? | No, despite what a biased film at the tax-supported Holocaust Museum implies (Apr. 27, 1998)

Is Jewish-Christian a Contradiction in Terms? (April 7, 1997)

Jews Oppose Baptist Outreach (Nov. 11, 1996)

Christmas and the Modern Jew | Christians often seem to lack both good missionary strategies toward Jews and sensitivity to their situation in life (Dec. 8, 1958)

Graham Feted By American Jewish Committee | In 1977, Graham walked a fine line between in his work ‘to proclaim the Gospel to Jew and Gentile.’ (Nov. 18, 1977)

To the Jew First | Witnessing to the Jews is nonnegotiable. (Aug. 11, 1997)

Billy Graham: ‘I have never felt called to single out the Jews’ | The evangelist discusses targeted evangelism in one of his most quoted statements (March 16, 1973)

Other Christianity Today articles have more specifically examined the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.