Most Christians assume that scientists who are atheists are anti-religion. I hear this stereotype a lot when I visit churches. And I used to believe it myself.

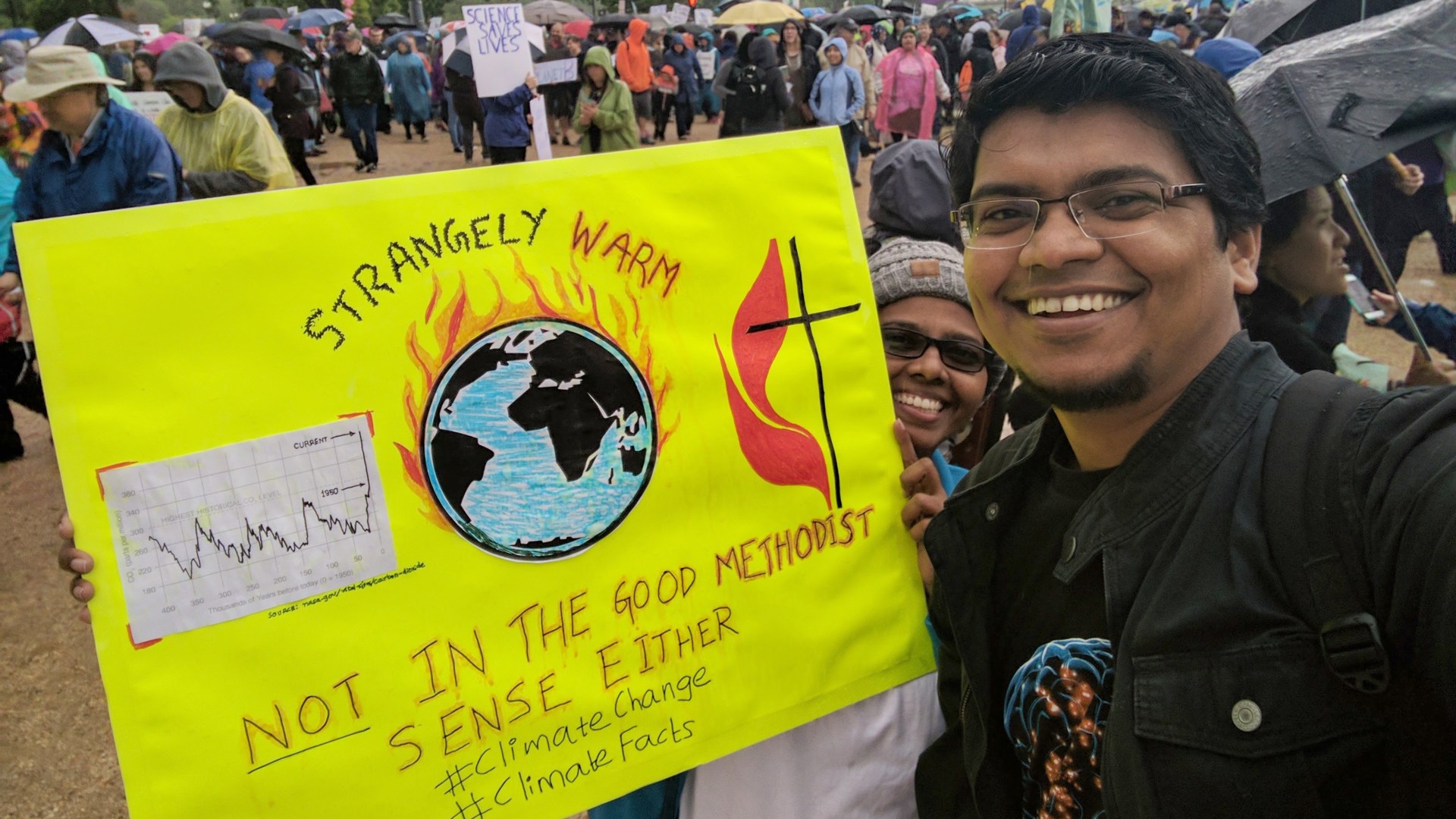

This weekend demonstrated it. Not because the March for Science has overcome concerns of divisions and managed to incorporate (most) religious viewpoints into the rally.

But what I have learned in the past 10 years paints a different picture about how scientists feel about religion and spirituality. And it’s not the same as Richard Dawkins, author of the bestselling The God Delusion.

During the past decade, I have led four large studies on the faith perspectives of scientists. The most recent is a research study published in 2016 on the religious views of scientists in eight regions: the United States, the United Kingdom, Taiwan, India, Hong Kong, Turkey, Italy, and France. For the study—the largest ever conducted on how scientists view religion—my colleagues and I surveyed more than 12,000 biologists and physicists, and interviewed more than 600 of them in depth.

Full disclosure: We did find that scientists at top universities are much less likely to believe in God than the general population in several national contexts. And many of them do believe that science is the only true way of understanding the world. However, few are actively hostile toward religion. The proportion who believe there is no God varied immensely by nation, ranging from a high of 51 percent in France to a low of 6 percent in Turkey. But I could count on two hands the number of atheist scientists we met who are as strongly anti-religious as Dawkins, the outspoken evolutionary biologist.

In some national contexts, a majority or near majority of scientists are what I call “complete modernists,” a term borrowed from a scientist we interviewed. These scientists either do not believe in God, or they do not know if God exists and they don’t believe there is a way to find out. They are not affiliated with any religious community, and they do not identify as religious or spiritual. These scientists are likely to be purveyors of scientism: the idea that science is the best or only way of knowing. They tend to be disproportionately male and in advanced stages of their careers.

But even among these scientists, few are hostile toward religion—or care enough about religion to actively speak out against it. If this indicates that younger scientists have more fluid views on the relationship between science and spirituality, this may have profound implications for the future of faith and science dialogue.

What we also found when we looked at our data on scientists’ attitudes toward religion is that a number of nonreligious scientists are what we call “spiritual atheists.” These scientists—ranging from about 1 in 33 in India to nearly 1 in 3 in Taiwan—do not believe in God, but they do believe in something beyond themselves. Something of greater purpose that matters to how they act and find meaning in the world. Some scientists we spoke with even suggested that not believing in God allows them to admire and exalt the natural world in a special way.

In the US, we found that more than 8 percent of atheist scientists and more than 14 percent of agnostic scientists say they are interested in spirituality—ranking near the middle compared to other countries and regions in the survey.

In Taiwan, 36 percent of scientists identify as spiritual but not religious. Most of them come from a Catholic or Protestant tradition. They are disproportionately represented among those in the early stages of their career (scientists in training, or those who are not tenured) and are more likely to be located at elite institutions.

In France, a country with a Catholic history and current commitment to strong secularism, 14 percent of scientists identify as spiritual but not religious. “I’m convinced that being open to another dimension, which is my definition of spirituality, is obviously giving you also another way of seeing science and doing science,” said one French scientist we spoke with.

“I aspire to be a spiritual person,” one US professor of biology told us during an interview. “To me, it’s almost like a kind of Golden Rule type of thing. … It’s sort of about aspiring to be good, not to be completely self-centered and have everything focus back on me and my own concerns.”

“The spirituality part of it … is why you do the work,” said a US physicist. “I mean, I’m interested in understanding how the universe began, possibly what its long-term future is going to be. I think those are certainly spiritual questions.”

And while Dawkins is recently best known for his popular rants against religion, my favorite quote of his speaks of the way in which he sees beauty in science. It is here that I think a surprising overlap exists between what some atheist scientists think about spirituality and what churchgoing people think. Both can see enormous beauty in science.

According to Dawkins:

The feeling of awed wonder that science can give us is one of the highest experiences of which the human psyche is capable. It is a deep aesthetic passion to rank with the finest that music and poetry can deliver.

And as people in my own church tradition say, “And that will preach!”

Elaine Howard Ecklundis the Herbert S. Autrey Chair in Social Sciences at Rice University and director of The Religion and Public Life Program. She is the author of Science Vs. Religion: What Scientists Really Think (2010) and the forthcoming (with Christopher P. Scheitle) Religion Vs. Science: What Religious People Really Think (2017).