In this series

The case of a Christian baker in Colorado who refused to make a cake for a same-sex wedding gets its big day in court today. While Jack Phillips’s legal team has emphasized his right to artistic expression as a cake decorator, many following his US Supreme Court case focus on another legal matter at stake: religious freedom.

Advocates on both sides anticipate Masterpiece Cakeshop Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission will set a nationwide precedent for whether the government can require businesses, organizations, and individuals to act against their own sincerely held religious beliefs—particularly following the legalization of same-sex marriage and equal rights granted to LGBT Americans.

As CT previously reported, Phillips’s refusal to bake the same-sex wedding cake in 2012 violated Colorado’s antidiscrimination law, and a state appeals court denied his free speech and free exercise claims. This spring, the high court opted to hear Phillips’s case, one of several cases involving Christian wedding vendors (such as florists, photographers, and caterers) currently making their way through state judicial systems.

Oral arguments in the case begin today at the Supreme Court. Most commentators expect Masterpiece Cakeshop will be a tight decision come spring, even with religious liberty defender Neil Gorsuch on the bench.

With Gorsuch, “there is some reason for optimism that the Court might narrowly find for Masterpiece Cakeshop,” Christian historian Thomas Kidd recently wrote for The Gospel Coalition. “If they do not, it will be a devastating blow to a number of Christian business people who have been disciplined under similar circumstances.

“A decision against Masterpiece Cakeshop would also raise more questions, such as whether a state can force Christian adoption agencies to place children with same-sex couples.”

During oral arguments, the court’s conservative justices challenged the gay couple’s counsel, American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) legal director David Cole, over how Colorado’s law applies to people of faith.

Chief Justice John Roberts asked if Catholic Legal Services would be forced to choose between “not providing any pro bono legal services or providing those services in connection with the same-sex marriage,” and Cole said if it were operating like a retail store, yes, the Washington Examiner reported.

Justices Samuel Alito and Gorsuch asked about accommodations for same-sex couples at religious schools, but Cole saw the example of schools’ free exercise as separate from public accommodations.

The case has elicited support from evangelicals, from fellow Coloradans at Focus on the Family to the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission. Officials from the Department of Justice also filed a brief on the baker’s behalf in September.

While the legal tensions between gay rights and religious rights have grown with legal recognition of same-sex marriage (Alito pointed out on Tuesday that gay marriage had not been legalized at the time Phillips turned down the cake order), the underlying issues surrounding religious belief and practice have plenty of precedent for the court to pull from.

Kidd and others bring up a 1990 case involving two men who defended their illegal use of peyote as part of a Native American religious ritual. In Employment Division v. Smith, the Supreme Court issued new operating procedures for when religion and the law come into conflict, stating that the free exercise clause “does not relieve an individual of the obligation to comply with a law that incidentally forbids (or requires) the performance of an act that his religious belief requires (or forbids) if the law is not specifically directed to religious practice and is otherwise constitutional as applied to those who engage in the specified act for nonreligious reasons.”

“The peyote case set the stage for Masterpiece Cakeshop,” wrote Temple University professor David Mislin on The Conversation. “It was in response to the case that Congress passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) of 1993. It required that laws restricting religious expression must show that they serve a compelling need.”

In other words, people of faith cannot be exempt from a law that doesn’t target a specific religious practice, and governments may pass laws that happen to limit religious freedom as long as they are shown to be the “least restrictive means of furthering a compelling government interest.”

“Colorado will similarly argue that it is in the public interest to prevent discrimination against gays and lesbians, and that this requirement is ‘generally applicable’ to all business people in the state, not just principled Christians,” Kidd said. “The problem is that it is hard to envision whom this policy might affect other than bakers of traditional religious views.”

Religious liberty scholars Thomas Berg and Douglas Laycock, in their amicus brief on behalf of Phillips and in an article posted at the Berkley Forum, argue that the case tests the meaning of “neutral and generally applicable” since Colorado sided with bakers who were charged with anti-religious discrimination for refusing to bake a cake with a message condemning homosexuality.

“Colorado deemed that refusing to provide a cake celebrating a same-sex wedding was sexual-orientation discrimination, but that refusing to provide a cake with a religious denunciation of same-sex relationships was not religious discrimination,” they wrote, advocating for a narrow and carefully defined exemption for Phillips.

“This distinction cannot stand: Both bakers declined to produce a message they found objectionable, a message associated with a protected class of customers.”

Berg tweeted on Tuesday that “#SCOTUS spent considerable time on free ex argument in #MasterpieceCakeshop, including other bakers who state treated differently,” and that their brief on the matter was mentioned in the arguments.

One of the most quoted lines came from Justice Anthony Kennedy, who said, “Tolerance is essential in a free society. It seems to me that the state in its position here has neither been tolerant nor respectful of Mr. Phillips’s religious beliefs.”

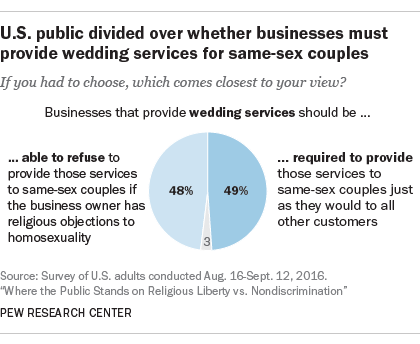

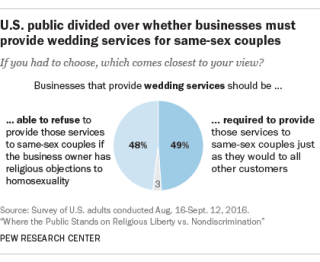

Americans are pretty evenly split over whether wedding vendors should be required to serve same-sex couples (49%) or should be able to decline on religious grounds (48%), according to a 2016 Pew Research Center survey. The groups most likely to say businesses should be able to turn down clients who conflict with their views were white evangelical Protestants (77%) and Republicans (71%).

Those on the other side of the case—including the ACLU—characterize Phillips’s first amendment claims as a license to discriminate.

They worry that a victory for Masterpiece Cakeshop will result in a slippery slope of dubious religious exemption claims. Similar concerns emerged amid other recent religious freedom fights, most prominently the Supreme Court ruling granting Hobby Lobby’s birth control exemption; but so far, there’s no evidence of those fears coming true.

“While there was an uptick of RFRA claims challenging the contraception mandate—culminating in Hobby Lobby and Little Sisters of the Poor—those cases have subsided, and no similar cases have materialized,” wrote Becket scholars Luke W. Goodrich and Rachel N. Busick in a study slated to appear in the Seton Hall Law Review.

“Courts have had no problem weeding out weak or insincere RFRA claims. If anything, RFRA has been underenforced.”

In one of the first empirical studies on religious freedom cases following the 2014 Hobby Lobby decision, the pair found that litigation citing religious liberty claims remains rare (about 0.6 percent of the federal docket) and still difficult to win. Of more than 100 religious liberty cases they analyzed from the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals, none involved clashes with LGBT rights. Religious minorities, defending issues like eagle feather ownership and Islamic law, were actually overrepresented in the successful claims.

In its final brief before this week’s oral arguments, Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF), which is representing Masterpiece Cakeshop in court, made the case that the kind of freedom of expression Phillips is fighting for extends past ideological lines. “Expressive freedom is central to human dignity. It requires that artists be free to make their own moral judgments about what to express through their works,” ADF stated.

Legal scholars Robert P. George and Sherif Girgis penned a New York Times op-ed that focuses on the Supreme Court’s historic protection against “compelled speech,” listing classic rulings in favor of objectors as well as cases where free speech trumped anti-discrimination laws.

They argue, as ADF has, that a Colorado cake baker’s conscience, creativity, and faith directly apply to his commercial decisions at work. “When the specific context is a same-sex wedding, that message is one Mr. Phillips doesn’t believe and cannot in conscience affirm. So coercing him to create a cake for the occasion is compelled artistic speech,” wrote George and Girgis.

Meanwhile, across the pond, the highest court in the United Kingdom recently agreed to hear a similar case, this one involving a Belfast bakery who refused to bake a cake with a same-sex marriage slogan. Like Phillips, the owners of Ashers Baking Company state that they do not discriminate against gay customers, and their issue lies with particular orders, not people. Despite—and because of—its legal fight, the bakery’s profits rose last year to nearly $2 million.