In summer 2003, American evangelicals’ book-buying habits appeared to be fueled by fear around political destabilization from the 9/11 attacks, war in the Middle East, and potential financial fallout around Y2K. The fictional series Left Behind sold over 80 million copies, and Dave Ramsey’s The Total Money Makeover sold 1 million copies around that time.

The idea of church was being reimagined: Gone were the lights, smoke machines, and conservative politics of megachurch practice; in their stead came icons, meeting in the round, and a decentering of the sermon in favor of liturgical elements, offering a sort of artsy smorgasbord for the spiritually curious.

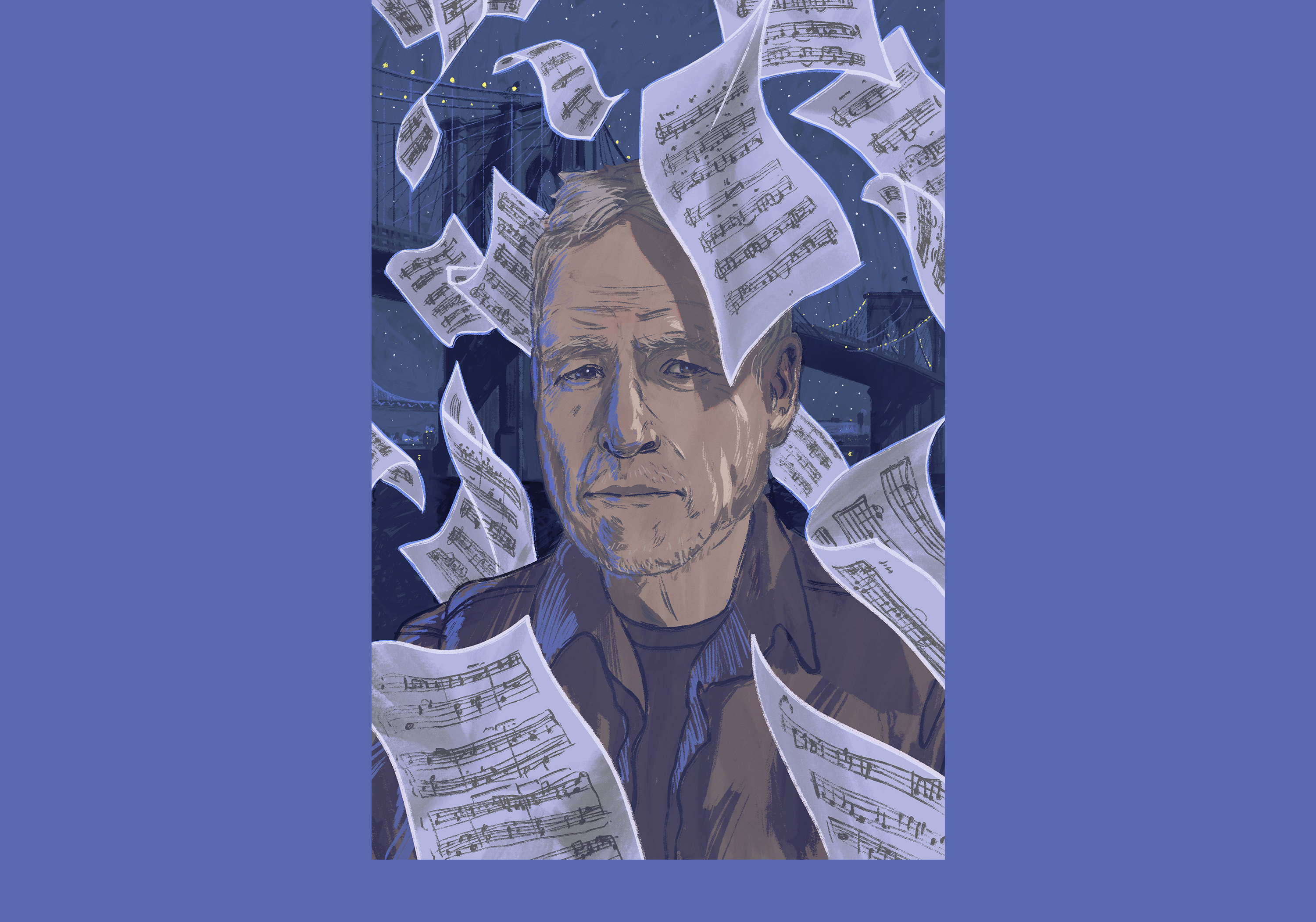

This was the world in which Donald Miller’s book Blue Like Jazz: Nonreligious Thoughts on Christian Spirituality became a sensation, sitting on The New York Times bestseller list for weeks and selling a million copies by 2008. The spiritual memoir captured “the emerging momentum of the Christian hipster set,” Brett McCracken wrote in Christianity Today in 2009 about those reacting against slick marketing in favor of liturgical practices.

In the two decades since, white American evangelical subcultures of the ’90s and ’00s have been scrutinized, reevaluated, and deconstructed in books, pulpits, and counseling offices, especially around purity culture, gender hierarchies, and abuse of power. But few evangelical writers have looked closely at Blue Like Jazz.

What was it about this memoir that captured an evangelical imagination for a whole generation? How did it speak to the hopes and fears of American evangelicals around the turn of the century? Blue Like Jazz attempted to correct a Christianity conflated with conservativism, but it has not offered a satisfying alternative. Both solutions—of legalism or license—ultimately are remnants of evangelical individualism. Both have left our pews empty.

Miller’s memoir joins a long line of confessional testimonial narratives, from Augustine’s Confessions to early American conversion narratives—with an important difference. This 21st-century testimony is not a rite of passage for entrance into a community but the record of an individual standing outside it, or at least alongside it—an observer reckoning with the evangelical experience while still longing to know Jesus.

The book’s “gritty” style—which CT described at the time as “Anne Lamott with testosterone”—was its appeal: a bit bloggy and conversational, slightly irreverent, more at ease with dissonance than tidy answers. And it resonated with disillusioned evangelicals.

Bookstore owner, publisher at InterVarsity Press, and current Evangelical Christian Publishers Association president Jeff Crosby watched Miller’s rise. He noted in an email interview with me that Miller’s titles “tapped into those early days of the ‘emerging church’ and ‘spiritual but not religious’ ideas being bandied about.”

He said Miller’s first two hits—Blue Like Jazz and A Million Miles in a Thousand Years—“scratched the itch we readers felt (but weren’t sure we could talk about) regarding the paradoxes of faith.” Jazz’s conversational familiarity was its success, and in 2012, it was made into a film.

While this “spiritual but not religious” tone was often associated with the emergent church movement, Miller never identified himself with emergent leaders like Brian McLaren or Rob Bell. But the tone and style of Miller’s prose resonates with what philosopher James K. A. Smith then wrote of the emergent church: Rather than a movement, “it’s better understood as a growing sensibility in the contemporary church.”

Readers bought Blue Like Jazz because of this sensibility. As Dale Huntington, lead pastor of City Life Church in San Diego, told me, “Miller didn’t preach at you. He sat you down to dinner, made a self-deprecating joke, and poured you a glass of wine.”

This connection resonated for religious and irreligious people alike and even led to conversions. Huntington’s father raised him in the Baha’i faith, but Huntington became a Christian at age 16. At age 20, his father was hospitalized from Parkinson’s disease. During the stay, Huntington read Blue Like Jazz to him aloud, and years later his father came to faith, largely through the influence of the book. Miller’s prose invited in those who lived on evangelicalism’s edges.

In the early 2000s, I had a different view of the American evangelical landscape. Newly married, my husband and I embarked on a journey across the Atlantic Ocean for seminary (him) and a PhD (me) in Edinburgh. In our years there, we were connected to both a small Scottish denominational seminary and a large research university; we joined a Church of Scotland parish church, yet we also looked with interest at the conversations happening back home.

While I knew of Blue Like Jazz in 2003, I read it only recently. Its punch and grit don’t quite land the same way 20 years later. The book is of its time and genre—more blog than memoir, oversharing in places (“I feel like a complete loser when I don’t have money”) yet trying just a bit too hard to be profound (“You cannot be a Christian without being a mystic”).

At the time, Blue Like Jazz offered a compelling story for American evangelicals to have Jesus without his bride. Jesus was presented as sensitive to the issues Miller and his fellow Christians faced in places like urban Portland. But the book’s style and message increasingly center the individual. In that way, it simply dresses the seeker-sensitive movement in a beanie and skinny jeans. In one passage, Miller prioritizes human decision over the cosmic work of Christ—he writes that there must be “something inside [him]” that earned Jesus’ redemptive work.

Miller recounts how he never really liked church and although he realized institutions were necessary, he didn’t like them. Yet his experience at one particular church, Imago Dei in Portland, was different. In 2005, Miller commented that this experience of a local church made him “feel parented and not alone.”

But by 2014, things had changed. Miller shared with his followers on social media that “church is not a huge part of my life. … Part of it [not attending church] was I’d disagree with what was taught. … I can’t get with the certainty.”

Christian outlets wrote with consternation about Miller’s shift away from the church, but it should not have come as a surprise. The signs were there. In Blue Like Jazz, Miller recounted, “The beginning of sharing my faith with people began by throwing out Christianity and embracing Christian spirituality, a nonpolitical mysterious system that can be experienced but not explained.”

Paul himself calls the gospel to Jews and Gentiles a mystery (Eph. 3:8–9; 5:32), and the good news of Jesus is personal and experiential, but Miller’s language is abstract and, over time, made it easy for him to distance himself from church. The sort of faith Miller pursued fails to mention Jesus, God’s Word, or Jesus’ church (as well as Paul’s many metaphors of the church as foundation, temple, or bride).

Where does one go to find this “nonpolitical mysterious system”? In what sorts of activities would one participate? Does it require others, or can I continually redefine through my own experience what is “experienced but not explained”? The language Miller uses about his Christian spirituality could equally be applied to psychedelics or witchcraft.

Some critics recognized this loose theological wordplay at the time, and others later. Tim Challies said, “Big box Christianity spawned…a rebellion” about which Miller and others wrote. Author Rachel Joy Welcher told me, “There wasn’t a category for what Miller was doing, but we knew we liked it. It felt edgy.” More recently, when writing on purity culture, she asked,

How do the ideas in these books I grew up reading hold up next to Scripture? What I found were so many extrabiblical rules and ideas that had no foundation in Bible truth, and yet were blindly followed by an entire generation of church kids like me.

Disaffected evangelicals found a home in Miller’s book and reached for new expressions of church. But a generation later, these disaffected evangelicals (and their children) aren’t moving from one tradition into another, from megachurch to hipster church. If Blue Like Jazz gave its readers permission to leave their parents’ Christianity, these same readers—like Miller himself—are now more likely to leave church altogether.

Given the amount and breadth of impact from church scandals in recent years, it makes sense that Miller and his original readers would desire to leave a broken institution. But in 2003, Miller named several Christian leaders to whom he looked with optimism because of their expressions of a relevant church in the 21st century. “The Cussing Pastor” Mark Driscoll, apologist Ravi Zacharias, and I Kissed Dating Goodbye author Joshua Harris were just a few.

Miller credited now-scandal-ridden Driscoll with encouraging him to attend Imago Dei church in Portland. He mentioned the late Ravi Zacharias’s teaching on the good of community—all while, we know today, Zacharias was abusing his power and sexually assaulting women. And he described Harris as “a vibrant kid who read a lot of the Bible,” “good-looking and obsessed with dating.” Today, Harris (once a part of C. J. Mahaney’s Sovereign Grace Church movement) and his wife are divorced and have walked away from Christian faith.

If the type of Christian spirituality that Blue Like Jazz enacts is detached from institutional guardrails and accountability and is not lived out in a spirit of communal renewal, repentance, and reliance on Christ, perhaps it’s not surprising to see the wreckage of the leaders Miller holds up.

We must be clear: No single commitment to theological or ecclesiastical tradition will insulate us from moral failure, abuse, suffering, doubt, or loss of faith. Following a sort of “nonpolitical mysterious system” did not insulate Miller or the leaders to whom he looked for guidance from falling into the trap of sin—through either abuse or sloth. However, this does not mean we need to end up where Miller or the tens of millions who have dechurched have landed.

In a passage near the end of the book (and from whence comes his title), Miller writes, “I think Christian spirituality is like jazz music,” a “music birthed out of freedom.” The phrase music birthed out of freedom requires us to ask: What is the end or goal of such freedom? For the generation coming out of the evils of chattel slavery in the US, freedom was thoroughly social, economic, political, and spiritual.

The freedom Miller explores in Blue Like Jazz is of an infinitely lesser variety: less potent; more platform-oriented and individualized; and ultimately untethered from place, accountability, and the unchanging Word of God.

Works of art shake us from our complacency even when they are of this lesser variety of freedom. We need new forms of art to awaken us. Especially when our institutions are healthy, we are afforded space to critique them and try out new, energizing forms—the sort of thing Miller does in Blue Like Jazz.

But when our institutions are weak and frayed, as many say they are now, the mature response is to root out bureaucratic rot while also strengthening our common bonds—the approach of a spade in one hand and sword in the other we see in Nehemiah 4:17. We defend and build simultaneously. We cannot simply critique church without seeking its peace and purity. We cannot tear down without also building up. We cannot sever spiritual growth from the manner and place in which Jesus says it takes place: the church.

Yuval Levin recently reminded us in the journal The New Atlantis that such institutional building is others-centered. We must take attention away from self to build for other (future) people. Levin’s criticism is sharp: “The inability to value those other people and judge them worthy of our work and sacrifice is a characteristic failing of a decadent society.” When we focus exclusively on our self-experience to the detriment of others, in the present or future, our cultural artifacts resemble a stagnant pond. There is no life there.

In 2020, Ross Douthat identified American society as being in a period of decadence, “something that comes on civilizations when they’ve reached a certain stage, and it’s not clear where they go next.” Decadence, Douthat believes, happens after the ladder of success has been climbed: a sort of stalemate of cultural production and dialogue. Movies rehash the same stories, and sequels rule the day. We often see this stagnation in form before we see it play out in content.

Blue Like Jazz’s form felt new and edgy for young millennials and Gen Xers in 2003. In hindsight, the fruit it bore is that of a decadent society where the self is ultimately authoritative, where individuals self-select into churches that feed their values (rather than sharpen like iron on iron), and where our Christian message is no different from the world’s—if we stay in the church at all.

There are other paths to take, however. When my husband and I moved to Edinburgh, the parish church we joined was evangelical in its history and sentiments. We sang weekly with organ accompaniment, drank tea with octogenarians, and worshiped with more than 27 other nationalities in a historic stone church building. This multicultural, multigenerational, and rather traditional church became the touchtone of my husband’s and my ministry and thinking then, and its tone still resonates with us today.

Because of that church, we value prayer for the global church, remembering we are a part of a diverse body across space and time. We remember in word and deed that our identity takes shape as we are built together into Christ’s body. In our 20s, we dreamed of church planting in a cosmopolitan city center, deeply motivated by Tim Keller’s rise to public prominence as we considered our future in terms of pluralism, contextualization, and gospel-centeredness.

These same values permeated our ministry wherever we’ve lived and served: in campus ministry, in the suburbs, and now at a church in a college town. For all the wounds we have received from the church and all the ways we have unintentionally wounded others, the church still provides us more than a provocative form or tone of spirituality. The church is the radiant bride of Christ himself.

Like Donald Miller’s own story, the books we write and the legacies they bequeath to future generations are complicated. Miller correctly concludes in his book, “I think the most important thing that happens within Christian spirituality is when a person falls in love with Jesus.”

But we must remember too that Jesus loves his bride. She is not perfect, but Jesus cleanses her of unrighteousness—in part now and fully at the fullness of time. We, as members of Christ’s body, must love her too.

Ashley Hales is editorial director for print at Christianity Today.