Certain Bible verses demand to be quoted in the King James Version, and Hebrews 10:25 is one of them. Following calls to “hold fast the profession of our faith without wavering” (v. 23) and provoke one another “unto love and to good works” (v. 24) is an exhortation even more direct: Christians should not be “forsaking the assembling of ourselves together, as the manner of some is.”

This is indeed the manner of some—today in ways the epistle’s unknown writer could not have anticipated. Human foibles are the same as ever, but 21st-century Christians have excuses for forsaking the assembly that first-century Christians could not muster: You can always just listen to a sermon podcast. You can pick up that extra shift or sleep a little longer or take your kid to the travel soccer tournament and make it up to God when the next episode drops. Well, you can do these things in the sense that this technology is available and no one will keep you from using it. But you can’t replace Sunday morning with a recording and presume that you’ve been to church.

Digital “attendance” is a misnomer. Even the best sermon podcast or livestream is not church, and a durable, dogged, in-person, on-paper, in-public commitment to a local church is a necessary part of the Christian life. Church is “not an optional add-on,” as theologian Brad East has written at CT. “It is how we learn to be human as God intended. Indeed, it makes possible truly human life before God.”

Sometimes, of course, we find ourselves in extenuating circumstances. Some Christians must contend with sickness or disability that makes church attendance physically impossible, perhaps for a long time. Their local congregations have a duty to bring church to them, insofar as that is feasible. Some Christians live under persecution or in places where there literally are no local congregations or have some other hardship that renders the exhortation in Hebrews a word of future hope rather than a near-term reality.

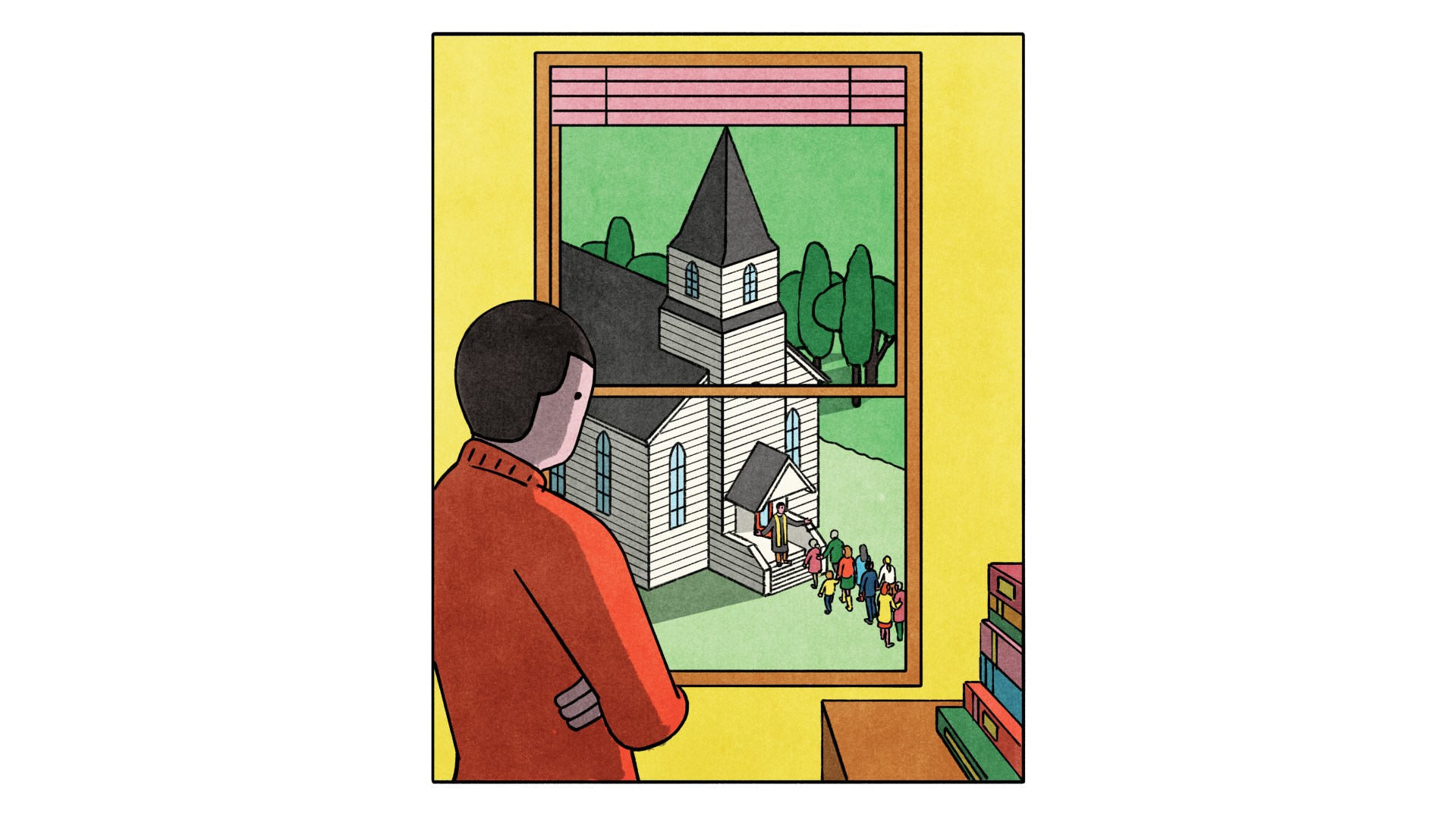

I am speaking not about these circumstances but about those typical of Christians in the modern West. I’m particularly speaking of Christians in America, which enjoys world-historic freedom, security, and comfort and which—even decades into record-level dechurching and church closures—is bustling with local churches. Here, for most of us, most of the time, professing to follow Jesus must mean going and committing to church.

And I do mean going. The church is the people, not the building, true enough, and there are contexts where that’s a needful reminder. My strong suspicion, though, is that America in 2026 is not one of them. We could stand to think a bit more often about church as a location to which we must bodily take ourselves. We must go, week in and week out, even when we’ve slept poorly or it’s storming or we do not feel like getting the kids out the door for the seventh day in a row.

It is somewhere we must go even when there is somewhere else we’d prefer to be. I understand how many Christians find themselves in a post–blue laws world struggling to avoid Sunday work shifts. Those of us with 9-to-5 jobs should be grateful that our work doesn’t interfere with Sunday worship and should do what we can to accommodate siblings in Christ who have more taxing and volatile schedules—perhaps including helping them find other work.

I have no similar sympathy for discretionary, time-intensive leisure activities that habitually take the hours that ought to be reserved for assembling. I’m thinking especially about travel sports, which in the past few decades have emerged as a major competitor to Sunday service attendance. If I may follow Hebrews in its bluntness, any kids’ sports league that convenes on Sunday mornings should either change its schedule under parental pressure or find that the only Christians on its rolls are Saturday Sabbatarians.

(Do I need to add a Screwtape Letters bit here? “My dear Wormwood, inspire in the patient a mad fanaticism for travel sports’ assurances of the well-rounded college application, the opportunity to learn real leadership, and the excellence that will translate into lifelong success. Never let him consider that this season’s soccer schedule will have him away from the sanctuary 11 Sundays of the next 13 or that he’ll be too exhausted on the other 2 to even contemplate arranging himself on a wooden pew at 9 o’clock in the morning.”)

The goods of church that we miss when we forsake assembling together are hard to overstate. In East’s phrase, the church, for all its flaws and failings, is a God-founded institution “finely tuned to the complex needs of the human experience—to help us with everything from early socialization to midlife crisis to dying well.” Even the best soccer season can’t compare; and neither can the sermon podcasts we may be tempted to substitute suffice.

On the podcast front, I speak from experience, because I embraced sermon downloads sooner than most. In my 20s, I moved to a small town in Virginia and began attending a nondenominational church within walking distance of my apartment. I met the pastors, joined the young adults group, and volunteered in the Awana kids’ program. I was married in the historic sanctuary where I’d learned to be an active member of the local body of Christ.

But early in my time there, it became apparent that the theological resources at my new church only went so far. I was in a season that today might be called deconstruction, though I didn’t experience it as the crisis the label now connotes. I was a 22-year-old exploring big theological topics myself for the first time, and I realized that the pastors at my church—though faithful, sensible, and kind—were working in a different register. I had questions beyond what they could realistically answer.

So I turned to books, to begin with. Then blogs. (It was 2010, after all.) Then, after Googling the name of an author I’d found helpful, I made a discovery: the sermon podcast.

Podcasts as we know them were only half a decade old at the time, and I still thought of sermon recordings as things that lived on cassette tapes in church vestibules. Soon I learned I could fill my screenless iPod with four archival sermons each week and spend my long runs under the tutelage of venerable pastors and expert theologians. And it was all free! I was surprised. I was impressed. I was hooked.

Over the next few years, those sermon podcasts shaped my faith and career alike. I no longer listen to any, except to make up the odd week that I’m out sick on Sunday. But it’s no exaggeration to say that without them, my life might look very different today. By no means do I recommend against them.

Yet for all their goods, digital media are not church, and church is not to be forsaken in their favor. Like a book or an essay, a podcast or video may offer guidance, instruction, and encouragement. These are elements of church, but they are not the whole. For that, we must assemble. It is in the assembly that we “hold fast the profession of our faith without wavering” and provoke one another “unto love and to good works.” It is by going to church that we learn to be the church.

The necessity of that lesson is why simply intending to go is not enough. “The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak,” we all know from too much experience (Matt. 26:41).

That truth is why, last spring, I knelt before the bishop of the Pittsburgh diocese one Sunday morning and was confirmed into the Anglican Church in North America. Confirmation wasn’t something I’d expected to pursue. I wasn’t raised in churches that practice it, but it’s offered by the church I’ve now embraced.

So I sought it, most simply because I could. Because it’s there. Because it’s another way to bind myself to this congregation, to say, “I’m in,” and I want other people to help me remember that when I’m inclined to forget.

I expect we are all so inclined at some point or another. Perhaps the inclination is particularly tempting in this time and place, in a society as noncommittal as they come. But the confirmation liturgy, developed from the 1662 version of the Book of Common Prayer, suggests to me that human weakness and inconstancy can flourish with or without the atomization and irresponsibility of our time.

“Will you obediently keep God’s holy will and commandments, and walk in them all the days of your life?” the bishop asks.

“I will,” the confirmands respond, “the Lord being my helper.” (Many other denominations do something like this in the membership vows or church covenant.)

It’s a realistic and humble reply—yet one that the next exchange suggests is not quite humble enough. After receiving that answer, the bishop immediately pivots to ask the whole congregation, “Will you who witness these vows do all in your power to support these persons in their life in Christ?”

Commit to faithfulness, yes, the question implies, but let’s think about contingency plans.

For me, I am glad someone is doing that thinking. It’s necessary and prudent. By divine design, the Christian life comes with support; the congregation answers yes.

It’s no knock on the Holy Spirit to recognize that we also need other people—that sometimes “the Lord being my helper” looks like an exhortation from your pastor or a book recommended by your small group or a casserole from the family in the next row. Sometimes we are too weak to hear God’s still, small voice (1 Kings 19:12, also in the KJV), but we can take in a text from a friend.

Naturally, this kind of give-and-take commitment goes for spiritual support and institutional maintenance alike. At our church, confirmation is a step beyond membership, one required to serve in select lay leadership roles. It provides an extra layer of theological instruction and scrutiny from our clergy, a layer that in some other traditions looks similar, in others is different, and in some may not exist at all.

Having seen firsthand what can happen in a local church without deliberate care in steering the congregation, I’m all for it. Our era is not (if any era ever was) a time of stasis, a time of ecclesial plenty, a time in which congregations can coast on the good work and established traditions of generations past.

Christian institutions, including local churches and denominational hierarchies, are inevitably human endeavors, subject to entropy like anything else in a fallen world. If we simply assume we’ll still have faithful, functional congregations 10 or 20 or 30 years hence, we won’t. They must be actively maintained, a task requiring steadiness and diligence, perseverance and forbearance.

I pursued confirmation to reiterate my aim to participate in that work. It is a way to solidify—to put down in writing and speak aloud in the sanctuary—the duty I already know to be real. Confirmation isn’t the only way to do that, of course. Many Christian traditions don’t confirm people, and confirmation is never explicitly mentioned in the Bible. Neither is formal membership, though that too strikes me as a good idea.

There are plenty of perfectly good ways to commit oneself to a local church, and (as a thoroughgoing Protestant) I don’t imagine God gets unduly worked up over the ceremonial details. Yet some kind of deliberate, public, in-print commitment is vital. “Not forsaking the assembling of ourselves together” is an active task.

The point is not about one exact arrangement or another. The point is to be in and to say so and to invite others to say it back to you when you’ve fallen silent. The point is the commitment, the orientation of your heart toward God, and the body of people whom you will serve and who will serve you in turn—people with whom you will assemble to worship, study, and imitate Christ.

Bonnie Kristian is deputy editor at Christianity Today.