In the spring semester of anno Domini 2000, I was a first-year college student enrolled in a survey of Roman history. It was there that I first read the Passion of Saints Perpetua and Felicity. Included in the printed packet of course readings were brief comments and discussion questions from the professor, Elizabeth Meyer. Introducing the text, she described it as “stunning.” And to 18-year-old me, it was.

And it still is, on every successive re-reading throughout the quarter century that has elapsed since my first encounter. I’m not alone. In my 15 years of teaching this text nearly every semester in survey classes, I’ve noticed that Perpetua and Felicity is one of the rare assignments that universally grabs students’ attention. Something about it speaks to both professional historians and college freshmen with minimal interest in history, to devout Christians and agnostics, to readers young and old.

To explain why, a brief orientation may be helpful. Two young women, Perpetua and Felicity, were martyred for their faith alongside other Christians in Carthage on March 7, AD 203. Perpetua was a respectable young matron with a nursing toddler. Felicity (or Felicitas, in Latin) was a pregnant slave.

Following her arrest and during her subsequent imprisonment while awaiting execution, Perpetua did something remarkable, a first for a Christian woman: She kept her own prison journal, interspersing real events from her life in these final months with vivid visions. After her death, an unnamed editor added an introduction and a conclusion (narrating the actual martyrdom) and published her journal.

The editor also included the shorter journal of Saturus, also martyred on this occasion—although his account gets lost in the shadow that Perpetua’s more prominent narrative casts over the document. I’ve read Saturus’ account time and again, but I still can’t really say anything about it. It’s remarkably forgettable. Felicity left no writing—as a slave, she was likely illiterate—but the editor mentions her both in the introduction and in the concluding portion that describes the martyrdom itself.

Perpetua’s journal is, by necessity, autobiographical. We get to know her in one place (prison) and time (the last days of her life). But might we be able to broaden the lens and tell her life story more completely?

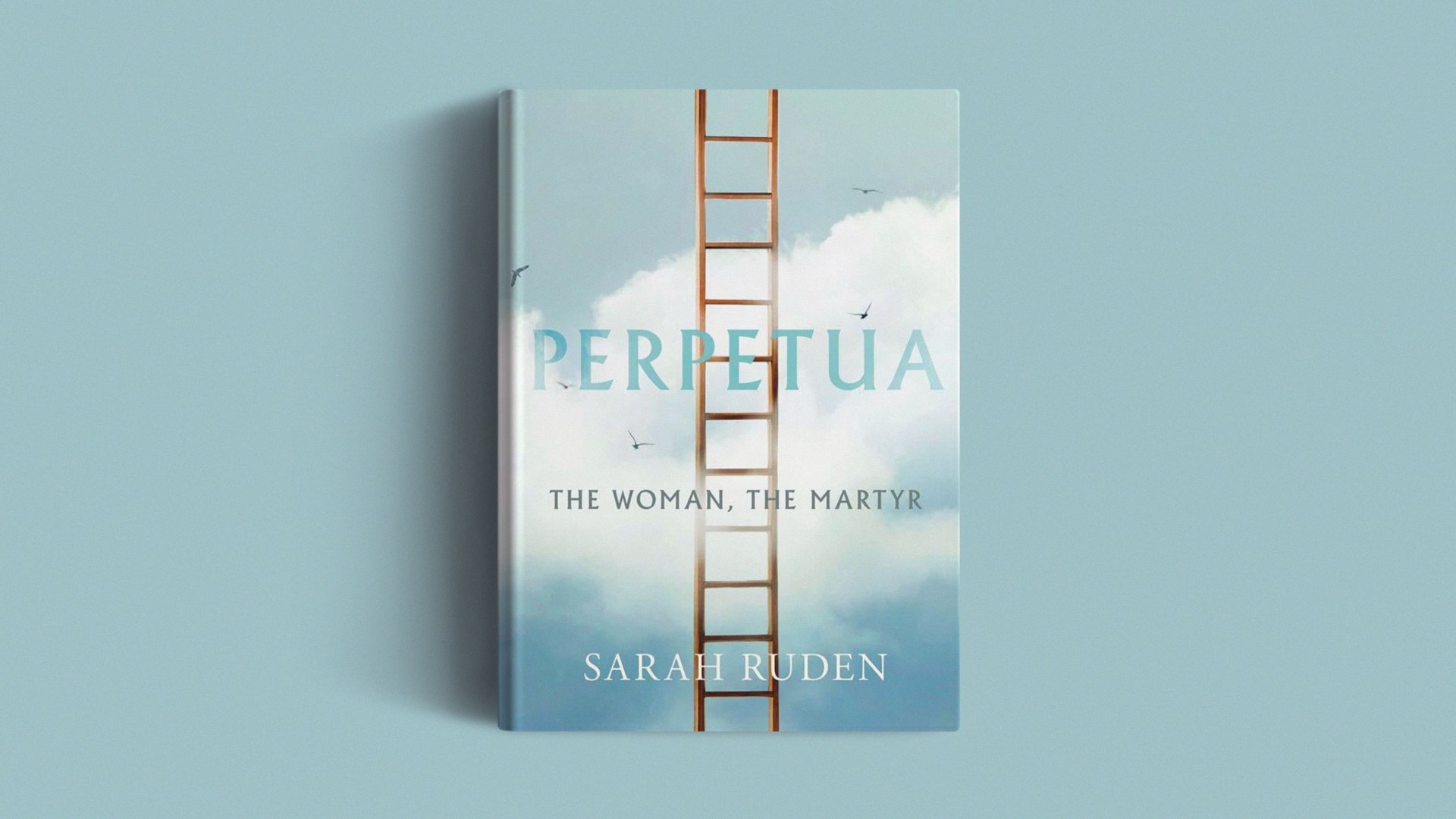

That is the aim of Sarah Ruden’s new biography Perpetua: The Woman, the Martyr, part of the remarkable Ancient Lives series from Yale University Press. Previous biographies, most notably Barbara Gold’s Perpetua: Athlete of God, have been heavily academic. Ruden aims to introduce Perpetua to thoughtful general readers.

In many ways, Ruden is the obvious candidate for the task. She is a well-known translator of Greek and Roman classics who has also written extensively about early Christianity and has even translated the Gospels. She is also a Quaker—meaning she comes at these texts from the perspective of a believer who has at least some sympathy for a figure like Perpetua. As Ruden notes in her introduction, “Socrates, Perpetua, Dietrich Bonhoeffer—it is fascinating to hear (even if only indirectly) of martyrdom from its practitioners.” Ruden has also written one previous biography—of the Roman poet Vergil—for the Ancient Lives series. She comes to this project well-versed in the difficult art of constructing a life story from mere traces of footprints eroded by time.

There is much to appreciate about the results. Ruden’s writing is characteristically accessible for nonspecialists. She includes her own translation of Perpetua’s reflections at the back of the volume; I would recommend those new to the account begin there. The translation aims to be colloquial, to convey the simplicity and lack of rhetorical artifice from Perpetua herself. Ruden’s analysis of the text’s literary features is undoubtedly the highlight of this book.

It can be tempting to idealize Perpetua’s writing style. At one extreme, she becomes a thoughtful and educated rhetorician simply because she dared write at a time when most women did not. A halo tends to attach itself to “firsts”: in this case, the first Christian woman writer.

At the other extreme, it’s easy to dismiss Perpetua’s prose. Considered objectively, it doesn’t quite pass muster when compared to the words of male Roman orators, like Cicero, or even church fathers, like Tertullian. We could say, “Perpetua was not a properly trained Roman writer, and it shows.” We would not be wrong—yet we would also be missing the point.

In response to both these views, Ruden recommends a parallel between Perpetua’s diary and that of Anne Frank, another writer who was decidedly not a trained professional yet whose journal we continue to find moving today when we approach it on its own terms. “What makes certain women’s writing literature in spite of everything is the superhuman-looking commitment not only to being oneself (any sociopath has that), and not only to becoming more than oneself and part of something much bigger,” reflects Ruden, “but also a commitment to sharing the imperfect and sometimes even shameful process—not always insightfully, not always honestly, but in one’s own unforgettable words.”

Ruden encourages us to read Perpetua’s writing slowly and carefully for what it can tell us about her as a person, a mother, and a Christian. These are good reminders, and the book does well to redeem Perpetua’s writing for modern readers.

Still, anyone approaching this biography with the expectation of finding a true biography—a story of a woman’s life from birth to death, or at least a broader time span than what we get in her journal—is in for a disappointment. In Gold’s earlier book about Perpetua, she was emphatic that we simply do not have enough information to write a true biography of the martyr. Ironically, though, in her reconstructions of Perpetua’s cultural, social, and historical background in Roman Carthage, Gold provided much more of a biography of Perpetua than we get in Ruden’s book, despite the latter’s insistence that this present volume is a biography.

Perpetua, Ruden admits, turned out to be a much harder subject than even Vergil, who was certainly not easy: “In my biography of Vergil, I felt I could speculate about certain turns of events (always identifying the speculation as such) because the evidence of his writings and of his social and historical context is massive, though personal information about him is skimpy. But for Perpetua, most of what we have is truth claims that do not fit together.” “Ironically,” Ruden reflects, “Perpetua’s visions are the most coherent, roundly convincing parts of her narrative.”

For an ancient biography, perhaps this is not a big worry—although, again, modern readers used to reading biographies of more recent figures about whom there is more information might be surprised.

We have no idea where and when precisely Perpetua was born (although Carthage is a major contender, another town nearby is a possibility); we don’t know her father’s precise social position (which means we don’t know Perpetua’s either); we don’t know her racial background (was she native to North Africa, or did she have some other background—e.g., Italian?); we don’t know anything about her husband or what happened to him to leave her alone with the baby at the beginning of her journal (did he die? Did he divorce her? A secret third thing?); we don’t know how she was converted; we’re not entirely sure of the details of her imprisonment, as there are several possible contradictions in her journal; finally, we don’t know for sure where she was martyred (again, Carthage is the most likely, but there are other possibilities).

Welcome to ancient history. The water is fine. It’s just very cloudy all the time.

But the real problem with this book lies in some highly idiosyncratic assumptions that Ruden brings to the text, which she strangely names the Suffering rather than the customary Passion. Deeply uncomfortable with martyrs and martyrdom accounts, Ruden criticizes the Christians who visited and encouraged Perpetua in prison for “making … cannon fodder out of susceptible people.” She repeatedly criticizes the pervasive “misogyny” that she sees as an integral feature of early Christianity—and she connects her discomfort with martyr accounts, like this one, to that devaluing of women. These are Ruden’s assumptions, which she takes as axiomatic and does not bother trying to prove in this book.

Yet the very survival of this text and accounts of other female martyrs puts these assumptions into question. Consider this: In The Missing Thread, a history of women in the ancient world up until early Christianity, historian and classicist Daisy Dunn lists an impressive catalog of ancient female writers. Virtually none of their writings survived. Why?

Perhaps because ancient readers did not respect these works as much as early Christian readers respected the work of Perpetua. The church at Carthage was the intellectual superpower of third-century Christianity. It speaks volumes that leaders in this church supported Perpetua’s writing to the point of saving this document, which would have been easy to destroy. Instead, they edited it after her martyrdom, published it, and made sure it received a reading.

In other words, an integral part of Perpetua’s story that Ruden dismisses outright is the local church, full of such “misogynistic” men as Tertullian. And yet this church was also likely the very audience Perpetua had in mind, first and foremost, when writing her journal.

In history, it is appropriate to take our primary sources’ words at face value unless they give us clear reasons to distrust their testimony. In the case of Perpetua, yes, many mysteries remain. But one thing is clear: She loved her church, and her church loved her. In our age of media obsession with dysfunctional churches, misbehaving leaders, and lukewarm believers, the stories of martyrs still offer a needed reminder of the love we should have for Christ and his bride. Most of us today are not called to die for our faith. But Perpetua’s love for her church still moves modern readers with its deep conviction.

Nadya Williams is the author of Mothers, Children, and the Body Politic: Ancient Christianity and the Recovery of Human Dignity and the forthcoming Christians Reading Classics: An Introduction to Greco-Roman Classics from Homer to Boethius.