On Tuesday, March 11, Jack Alvarez attended mass at Ina ng Lupang Pangako Parish in Quezon City. The occasion: thanking God that the International Criminal Court (ICC) had arrested Rodrigo Duterte.

The former president’s war on drugs had claimed the lives of many of the attendees’ children and spouses, who brought photos of their loved ones and placed them on a table by the sanctuary. Locals attended the service—and so did those who had to travel more than an hour to get there.

The evening concluded with “Pananagutan,” or “Brother to Brother.” A tearful crowd sang in Tagalog, “We are all responsible for each other. We are all gathered by God to be with him.”

“Many were happy that they were finally getting justice,” said Alvarez, who pastors Komunidad kay Kristo sa Payatas (Community of Christ in Payatas), an independent evangelical church about a ten-minute walk away that serves the poor and densely populated barangay next to a former dumpsite.

During the Duterte administration, law enforcement shot dead between three and four Payatas residents a day, Alvarez said, recalling one day in 2016 when police shot five men in the heart after accusing them of being drug dealers and of fighting back against the police.

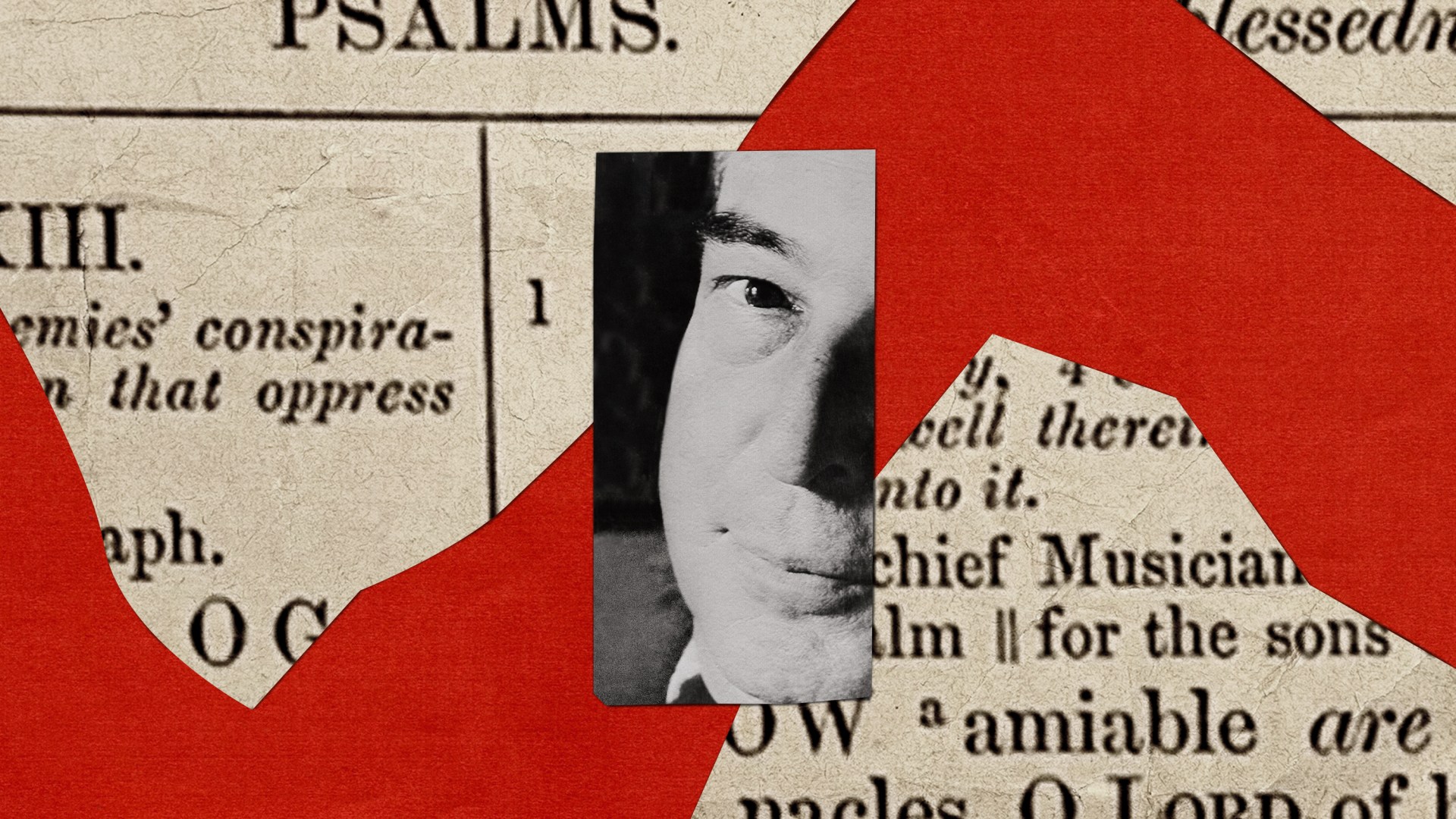

Outside of Ina ng Lupang Pangako Parish, Christians across the country are divided over the ICC’s arrest and charges, which accuse Duterte of killing thousands of people while serving as the head of the “Davao Death Squad” and later while overseeing the country’s law enforcement after he became president. Starting while he was mayor of Davao City, Duterte threatened drug dealers, saying not that he would bring them to justice but instead that he would kill them. Later, police and unidentified shooters executed these extrajudicial killings (EJK).

In Davao City and across Mindanao, the country’s second largest island, thousands of Duterte’s supporters took to the streets, lighting candles, raising placards with words like “We Stand with Duterte” and “We Love You, Tatay,” and praying for his freedom and safety.

“I’m almost 68. I’ve seen many presidents in my lifetime, and even if my opinion is unpopular, I think he’s the best,” said Maria Palacio, a pastor who serves at the prophetic ministry House of Unlimited Grace.

The longtime Mindanaoan has a picture she took with Duterte when she visited Davao—she had been waiting on the sidelines of the photo queue when he called her over—and gushed about how he was “down-to-earth and acted like a regular citizen.” Using his childhood nickname, many of his supporters called him Tatay Digong, or Father Digong, a gesture that came because residents “felt safe” when he was in power, Palacio said.

“People aren’t used to rulers with an iron fist,” she said. “But when he became mayor and president, he cleaned everything up, and drug addicts were scared.”

One of Palacio’s family members struggled with a drug addiction that often left him violent. She felt grateful for policies that she believed directly combatted a problem that had ruined her loved one’s life and hurt her family, and she said she would have voted for him again in the upcoming mayoral elections—Duterte announced he would seek another term last fall—had she still been based in Davao.

Whereas Catholics and mainline Protestants have been grateful for the ICC’s arrest, evangelical reactions have been largely determined by larger politics of the regions where they are from, said Aldrin Peñamora, director of the Philippine Council of Evangelical Churches’ Justice, Peace, and Reconciliation Commission.

On social media, some Duterte supporters have blamed current president Bongbong Marcos for Duterte’s arrest, Peñamora said. In 2022, Marcos won the presidency, and Duterte’s daughter Sara Duterte won the vice presidency. But the relationship disintegrated when Marcos began to distance himself from Duterte’s drug-war policies. Last year, Sara Duterte threatened to kill Marcos by assassination if she were murdered, and she was impeached by the House of Representatives last month.

Beyond the political drama, misinformation about the president’s whereabouts, images of Duterte prayer rallies created with generative artificial intelligence, a rumored arrest of First Lady Liza Marcos, fake quotes, and false accusations about the ICC have influenced many Filipinos, including Christians.

Duterte is fortunate to at least have gone through due process, unlike the 30,000 who were immediately killed during the drug war, said Gabby Go Balauag, a staff member at Hope of Glory Community Church in Marilao, Bulacan. Further, he wrote on Facebook, Christians’ support for the bloody drug war raises serious moral and theological concerns, among them one’s understanding of the sanctity of life, the emphasis of compassion over condemnation, and the importance of government accountability.

“I can’t align my faith with Duterte’s rhetoric of murder, violence, and abuse,” he said. “This isn’t God’s heart for governance and for disciplining our countrymen.”

His senior pastor, Jonel Milan, tries to keep his congregation informed about current events. Every day from 7:00 to 7:30 a.m., the church gathers to pray about different political issues facing the country. Among them are the West Philippine Sea dispute and the upcoming senatorial elections in May. Balauag said that the majority of congregants agree that the war on drugs was wrong and are praying that the ICC will uphold justice.

On March 14, Duterte appeared in court in The Hague, though his hearing will not start until September 23. Over the next six months, Peñamora hopes church leaders will be careful about not letting politics splinter their congregations. He prays regularly for Duterte’s salvation and spiritual well-being.

“Let’s not forget the thousands of victims and their families,” he said. “My prayer is for the church to have a moral vision to care for them.”

Back in Payatas, Alvarez volunteers with Bawat Isa Mahalaga (“everyone is important”), an evangelical ministry that encourages Filipino Christians to become more civically engaged. As part one of its initiatives, each week, he and his congregants join with Ina ng Lupang Pangako Parish members in giving packs of rice to those orphaned and widowed during the drug war.

“There is no part of creation that is not under the lordship of Christ, and this must reflect in how we help orphans and widows,” Alvarez said. “It isn’t too late for evangelicals to be vocal against EJKs.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the ministry that Alvarez volunteers with.