I have been making books my entire life.

In grade school, my teacher assigned a series of reports on the provinces of Canada. After writing one each week, I gathered them up, added a table of contents and a title page, and bound them with yarn. No one told me to do that. I just did.

In high school, a friend and I self-published a novelty humor book and sold hundreds of copies to friends and family. That was decades before self-publishing was a thing.

No wonder that when I joined the editorial staff of InterVarsity Press 50 years ago, I felt like the town drunk who was given charge of the local distillery.

Unsurprisingly, then, I drank in Adam Smyth’s The Book-Makers, which celebrates the characters who have crafted books over the past half millennium. Through the lenses of 18 lives, Smyth, a professor at Balliol College, Oxford, provides not a complete history of the physical aspects of bookmaking but a representative and very human story centered in England.

We meet dedicated bookbinders, ambitious entrepreneurs, clever (and impoverished) inventors, innovative distributors, pioneering typographers, obsessed artisans, renegade publishers, and dreamers … always some dreamers. They dream of making art, of making money, of making a difference.

Smyth’s narrative begins in 1501 with Wynkyn de Worde, one of the first and most prominent printers on London’s Fleet Street, soon to become the center of British publishing. De Worde arrived as an immigrant from Germany, where Gutenberg’s revolutionary printing press had originated only decades prior.

In this early era of printing, much of England’s publishing industry relied on skilled workers from the continent. But this dependence generated pushback. Within a few decades, England passed laws limiting foreign workers. Yet “significant numbers of skilled bookmen continued to arrive from abroad,” writes Smyth, “particularly in periods of crisis.”

De Worde enjoyed some patronage from the aristocrats of his era, but his publishing model looked beyond the interests of the powerful to serve a wider range of readers. He combined what publishers have needed ever since—business know-how and a savvy understanding of one’s audience. He printed not only religious texts but also popular works such as Sebastian Brant’s highly successful 1494 satire, The Ship of Fools.

In emphasizing the physical nature of books, Smyth engages all our senses as he transports us back 500 years to de Worde’s workshop.

The place is surely cramped, and probably dark; too hot in the summer. Candles flicker. Just-printed sheets hang from high ropes like drying laundry. The windows are paper, not glass, a cheap way to block sunlight from the printed pages. But—in winter—so cold. Scraps of paper lie around—old proof pages, torn sheets—ready for reuse as improvised window covers, or wrappers, or to fill a thin space between wobbly letters: there is a thriftiness to everything, a spirit of maximal extraction. And the place stinks: from bodies printing 250 sheets an hour for twelve-hour days; from the strongly alkali lye, bubbling in a tub, used to clean the lead type; from the beer spilt on the floor, brought in every couple of hours by the young apprentice; from the linseed oil boiling in a cauldron over logs, nearly ready to be mixed with carbon and amber resin to make ink; and from the buckets of urine in which the inking balls’ leather covers soak and soften overnight.

Smyth has fun with his material, and as a result, so do readers. Take, for instance, his account of the delightfully named William Wildgoose, a prominent bookbinder of the era. “We might think it’s unlikely,” he writes, “that there were dozens of individuals named William Wildgoose honking around Oxford, but in fact records suggest an extended family in the Oxfordshire area in the seventeenth century.”

Wildgoose worked at a time when printers sold books as unbound stacks of paper, allowing customers to find a preferred bookbinder. The famed Bodleian Library at Oxford (founded in 1602) often turned to Wildgoose in its early years.

Typography receives its due in Smyth’s portrait of John Baskerville, a Birmingham-based printer, and his wife and business partner, Sarah Eaves, who brought stability and expertise to their joint enterprise. Beyond creating an elegant mid-18th-century typeface, Baskerville immersed himself in each aspect of the book—the paper, the ink, the page design, and the printing process itself. Baskerville’s books were objects of craft to be admired in themselves.

In Baskerville’s time, the world’s most famous American was a scientist, an inventor, a political activist, a diplomat, and a writer. But he most commonly identified himself as a printer. Benjamin Franklin learned that trade in Boston, Philadelphia, and London. (The recent Apple TV+ series Franklin shows him employing that training to illegally print pamphlets in France supporting the American Revolution.)

Consistent with centuries-old trends in his trade, the bulk of Franklin’s printing was transient and ephemeral. He made his fortune and reputation on job printing. Pamphlets, sermons, lottery tickets, paper currency, newspapers, government documents—these were Franklin’s daily diet. The major exception was his yearly almanac, which also had a temporary character despite taking the form of a book.

When Smyth turns to the history of paper, he reminds us that the human penchant for prejudice has been constant over millennia.

The Chinese invented papermaking 2,000 years ago, before their methods transitioned to the Arab world 800 years later. These techniques finally arrived in Europe around the 11th century. At first, Europeans distrusted paper because it was introduced by Jews and Arabs. Once they understood its value, writes Smyth, “they set about systematically forgetting its Arabic, Chinese past, appropriating paper as their own, and refashioning its history into a story of European ingenuity.”

The tale of Nicholas-Louis Robert delivers another blow to human nature’s reputation. Though the Frenchman gained a patent in 1799 for the first papermaking machine, he suffered from the greed of those who blatantly stole his designs, robbing him of recognition and remuneration alike.

The case of Charles Edward Mudie also proves there is nothing new under the book-publishing sun. A century and a half before Jeff Bezos and Amazon, Mudie dominated book distribution. This 19th-century purveyor of British culture “found a very cheap way for hundreds of thousands of new readers, including women, including those far from London, including those, indeed, scattered across the globe, to have access to books they could otherwise not afford.” His scheme was to loan books for an annual subscription price that cost less than three novels. And for those living in London, he even provided free delivery. Sound familiar?

Books have not been the sole domain of entrepreneurs. They have also been objects of devotion, even obsession. One fad straddling the 18th and 19th centuries was epitomized by collectors Charlotte and Alexander Sutherland. They (and many others) would take a volume of, say, British history and augment it with hundreds of separate portraits and illustrations. This could entail expanding a single book into dozens of oversized, beautifully bound volumes, all for personal delight rather than public consumption.

Another monument to obsessive book artistry was the career of English bookbinder Thomas Cobden-Sanderson, who produced a landmark five-volume Bible in 1904, followed by deluxe editions of Shakespeare’s plays. Cobden-Sanderson had commissioned a new, meticulously crafted metal-type font modeled after 15th-century designs. But his devotion turned monomaniacal in his last years, when he worried that second-rate mechanical printing outfits would deploy his handiwork without honoring his care and craftsmanship. In 1916, over several months, he secretly dumped hundreds of pounds of precious type and tools into the River Thames.

Smyth brings us into the last hundred years by highlighting the literary efforts of two small British presses—Nancy Cunard’s Hours Press and Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s Hogarth Press. Their community of authors included Ezra Pound, Samuel Beckett, E. M. Forster, Gertrude Stein, Sigmund Freud, and John Maynard Keynes. Emphasizing the manual (rather than mechanical) press and catering to specialized tastes, this movement sought “to uncouple publishing from the restrictions of the market.” In this, Cunard succeeded admirably, since her Hours Press lasted only three years before being sold off.

The Book-Makers compels us to ask, from the perspective of our digital world: Is reviewing the history of print merely an exercise in nostalgia or irrelevance? We may remember apocalyptic predictions from 20 years ago that print books were doomed. Yet they have survived.

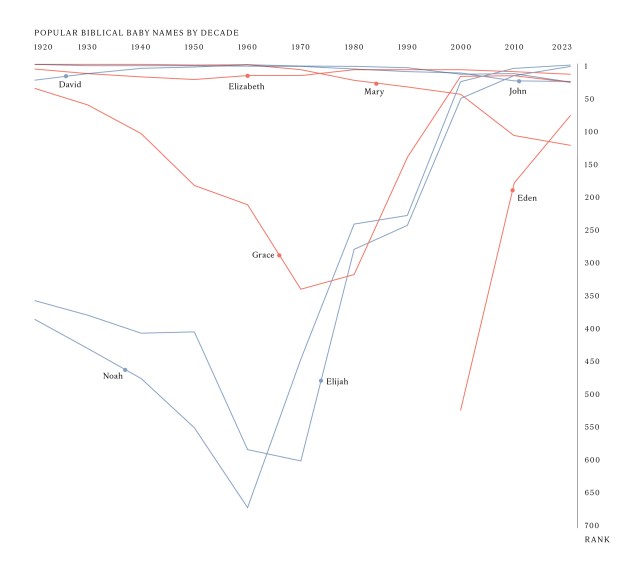

Today, according to Association of American Publishers data, about three print books are sold for every digital book (ebook or audio), a ratio that has held steady in recent years. Within the US, combined sales have also remained stable, hovering around a billion units each year. That is bad in an economic system that often relies on growth for survival, but it is remarkably strong in the face of illiteracy trends, entertainment options, and the flood of news and social media. As readers and citizens, we are drowning in information yet starved for wisdom.

That is why, amid all the activities described in The Book-Makers, the gravitational center comes, for me, in chapter 3, where the book slows to a meditational pace. In the 1600s, there was a religious community at Little Gidding, 30 miles northwest of Cambridge, England. There, over decades, Mary and Anna Collett labored with great care and workmanship, cutting and pasting personal editions of the Bible to create a single harmony of the Scriptures. While this may look like an act of destruction, it embodied a posture of deep reading—of emotionally, intellectually, and spiritually encountering the text, all enhanced by physically engaging with the printed page. Though Smyth exhibits no overt religious commitments, he reveals rare sensitivity. He does not treat the Colletts with cynicism or ridicule, as would be so easy. He rather accepts them for who they are, much as they saw themselves: two people in community, seeking to grapple with the Word, to meditate on it deeply, and to let it change them.

Andrew T. Le Peau headed the editorial department at InterVarsity Press for three decades. He is the author of Write Better and Mark Through Old Testament Eyes, and he blogs regularly at Andy Unedited.