Kenya’s leaders aren’t saying much publicly about the security force they plan to send to gang-embattled Haiti. But they’re talking a whole lot with God.

Last month, as armed groups escalated their insurgency in Port-au-Prince and plunged Haiti deeper into a historic humanitarian crisis, pastors advising Kenya’s government met for three days at a hotel in Nairobi to pray.

In a sky-blue conference room at the Weston Hotel, three Kenyan pastors joined Haitian and American ministry leaders and Kenya’s first lady, Rachel Ruto, to plead for divine assistance for the beleaguered Caribbean country. They prayed for the 2,500-person multinational police force Kenya has volunteered to lead to help Haitian law enforcement. At one point, meeting participants told CT, group members wept.

After two days of prayer, the first lady dropped in on an album release party in another part of the Weston, which President William Ruto owns, and announced her office had formed a prayer committee for Haiti. “We cannot allow our police to go to Haiti without prayer,” Rachel Ruto told fans of the Kenyan gospel group 1005 Songs & More.

Kenya agreed last October to spearhead a UN-authorized international security mission to Haiti, but the deployment has faced various delays, including legal challenges and questions about funding.

The prayer marathon was part of a broader effort by the Ruto administration to strategize “a spiritual solution for our police and people of Haiti,” according to the first lady. The initiative, coordinated by the administration’s “faith diplomacy” office, has so far included a national prayer gathering, a 40-day prayer guide for Haiti, and an official fact-finding trip to the United States.

For a government that has been largely tight-lipped about the police mission, the church outreach programs represent one of the most visible ways the administration has engaged the public about the plan. The Rutos, who are outspoken about their evangelical faith, took office in 2022 thanks to what many of the country’s Christians say was divine protection during a disputed election.

“Let us thank the Lord who gave our president such a burden to think about Haiti,” Julius Suubi, a pastor and spiritual advisor to the Rutos, told a crowd of roughly 1,000 pastors at an April 15 prayer service in downtown Nairobi. “Which president in Africa ever thinks about a country outside Africa?”

Earlier this month, the same group of pastors and the first lady’s staff traveled to the United States to meet with church and business leaders, US and Haitian officials, and representatives from law enforcement and the military. They also participated in a Zoom meeting with gang coalition leader Jimmy “Barbeque” Chérizier, according to Serge Musasilwa, a member of the delegation.

Musasilwa, the country director for a ministry in central Kenya called Segera Mission, said the group wanted to hear from people across all sectors of Haitian society, to better understand the challenges Kenya’s police would face. President Ruto commissioned the team to provide context to inform law enforcement and to increase the security mission’s odds of success, he said. The pastors wanted to know what civil society groups and churches say the problems are; they asked about solutions; they inquired about how well trained the gangs are and what motivates them.

The group is scheduled to present its findings to the president this month, in advance of a presidential trip to the United States in May that will include the first state visit by an African president to the White House in 16 years. Ruto, who says his country has a moral obligation to help Haiti, has insisted the security mission is moving forward—despite delays in funding the Biden administration has pledged to underwrite it ($40 million are currently being held up by Republicans in the US Congress).

Musasilwa is optimistic. “It’s going to be a new beginning for the country,” he told CT. But he says the president is eager to avoid mistakes that have plagued previous interventions in Haiti. “If you are guided only by the emotion, or by desperation, the risk is very high that you’ll find yourself on the list of those who failed.”

Part of the fact-finding trip was simply about identifying who is functioning as Haiti’s government. Haiti does not have a single elected official currently in office; the country has named a transitional council that is supposed to appoint a prime minister and prepare for eventual elections, but the council has not yet been sworn in.

For instance, Musasilwa said, he met for six hours with Haiti’s ambassador to Qatar, Francois Guillaume, trying to understand Haiti’s government structure.

“Assume that our forces are in Port-au-Prince today and they arrest one of the gangs,” Musasilwa said. “They would take him where? There is no judiciary.”

The multinational security mission, which many observers had hoped would deploy months ago, has been delayed in part by uncertainty over who exactly Kenyans would be working with. Haiti’s outgoing prime minister, Ariel Henry, signed partnership agreements with Kenya on March 1, shortly before gang attacks closed Haiti’s main international airport and stranded him outside the country.

“As much as we want our troops to come tomorrow, first of all, there’s no government in Haiti, so no order,” said Davis Kisotu, a pastor at an independent Pentecostal church who is close to the Rutos.

Kisotu, like the other Kenyan ministry leaders who traveled in the delegation, serves on the National Prayer Altar, a team in the first lady’s office that oversees church services at the presidential residence and works with pastors across Kenya to pray for government. They are not the only government team making preparations for the mission; Haitian officials have visited Nairobi, and Kenyan law enforcement have met with their Haitian counterparts in Port-au-Prince.

But while bureaucrats in New York and Washington iron out the operational details for the police mission, one of the Prayer Altar team’s jobs is also “to mobilize prayer and the men of God—Haitian pastors, US pastors and Kenya pastors and prayer warriors across the nations.”

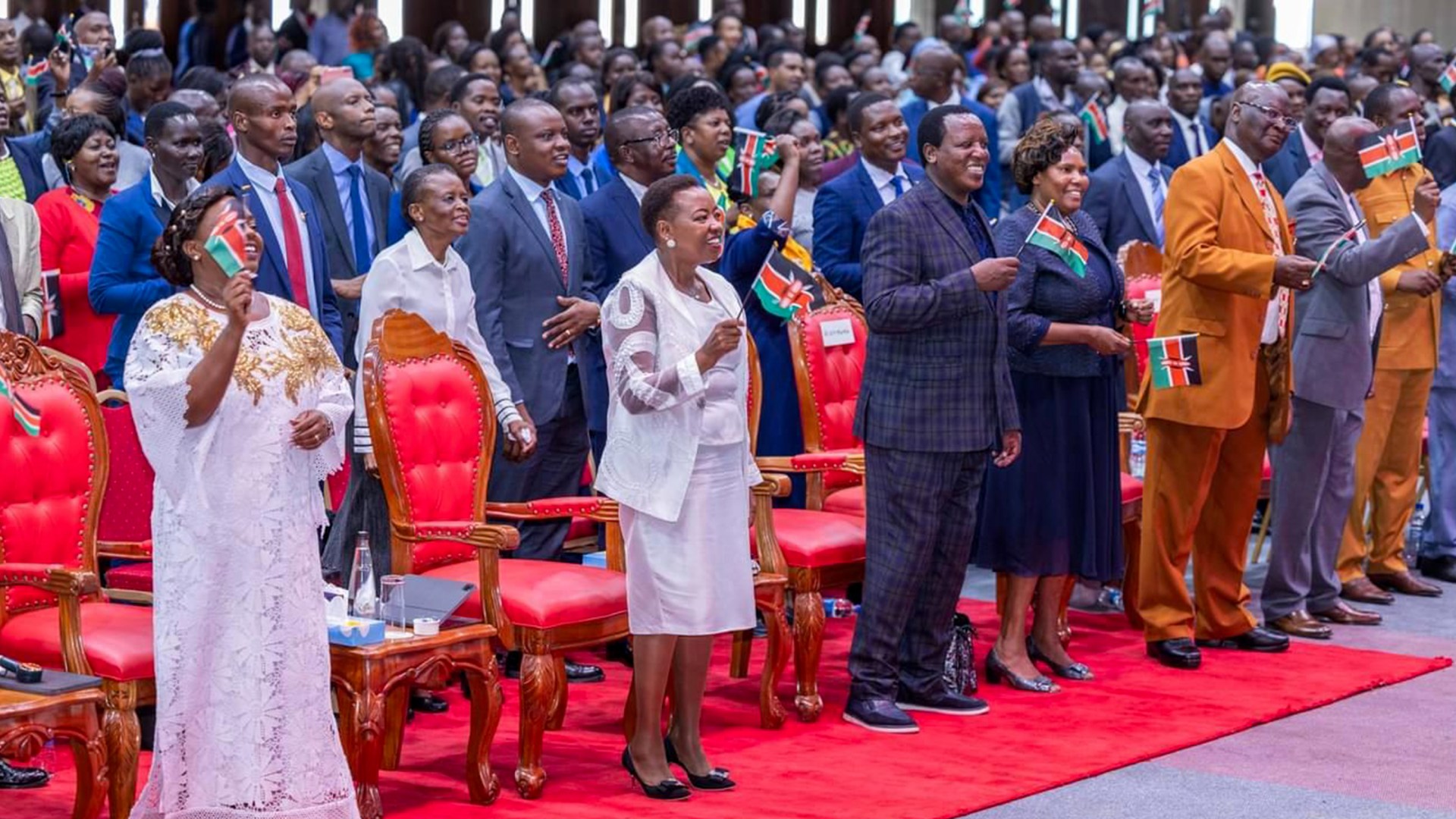

To that end, pastors from across the country gathered Monday at the Kenyatta International Convention Centre, a facility nestled beside Kenya’s parliament and supreme court in the heart of Nairobi. The first lady addressed an energetic and supportive crowd as it waved flags and prayed for Kenya, for Israel, and for Haiti.

Other speakers, veering at times into tones fit for a campaign rally, prayed for peace in Haiti and praised President Ruto for his commitment to use Kenyan power as a force for international peace. Asunta Juma, host of Tracing the Mantles, a popular evangelical talk show, declared that Ruto has found favor with many world leaders because God’s favor is upon him. “We elected a leader who is going to provide leadership to the nations of the world,” she said.

The national gathering came at a time when other international church groups are in the midst of their own pushes for concerted prayer for Haiti. Across the United States, mission groups have been emailing and texting supporters with regular prayer requests. Baptist Haiti Mission, whose leadership has consulted with the Ruto administration, wants to draw a million prayer partners into its prayer campaign, which includes weekly livestreams.

In Kenya, the first lady’s faith diplomacy office has so far recruited at least 200 pastors to lead their churches through 40 days of prayer for Haiti, using a prayer guide produced by the National Altar. A copy of the 132-page guide, provided to CT, includes sweeping prayers for healing from the trauma of slavery, for deliverance from the “generational bondage and powers” of witchcraft, for the healing of deforested land, and for God to “flush out gangs and insurgents from their hiding places and deliver them into the hands of the police.”

“There’s something about Haiti that has captured the men and women of God in Kenya,” Suubi, the National Altar member who also leads Highway of Holiness Ministries, told CT.

Not every Christian leader is enamored.

Many Kenyans, including mainline Christians and some evangelicals, oppose their country’s involvement in Haiti. Lawmakers sued to stop it, leading to an injunction by Kenya’s highest court that the administration has tried to work around.

While Kenya’s last two presidents were Roman Catholics, Ruto rose to power with significant help from the country’s charismatic and Pentecostal church communities, many of whom view any criticism of Ruto as spiritual attack.

Sammy Wainaina, former provost of All Saints Cathedral in Nairobi and one of Kenya’s most prominent Anglicans, says the Kenya police are not equipped to deal with the political situation in Haiti.

“Kenya is currently facing a big shortage of police force,” Wainaina said. “Countries like the US should address the problems they have created in Haiti.”

Enoch Opuka, a lecturer on development studies at Africa International University who also happens to have taught Ruto in high school, thinks Haiti’s grinding poverty must be addressed before any other solution can work. Deploy massive amounts of aid, cancel all of Haiti’s debts, and facilitate dialogue between armed groups and government, he said; don’t deploy police.

“You don’t remove hunger by sending soldiers,” Opuka said.

Musasilwa is aware of the criticisms, which is why he says the fact-finding team has focused on listening to people across Haitian society and studying the failures of previous interventions in Haiti.

Among the recommendations in his report, for instance, will be that Kenya help Haiti facilitate a peace and reconciliation conference to bring as many Haitians as possible into conversations about its future—including gangs.

“We are not there to resolve their problems,” Musasilwa said. “We are there to support them in the solutions that fit for them.”

He said he has learned something for certain in his many conversations and his research into what has not worked in Haiti:

“If Kenya wants to succeed in this mission, there is only one key: It’s not to be perceived in one way or another that they are implementing US politics,” Musasilwa said. “That is something to pray for.”

With reporting from Moses Wasamu in Nairobi.

Andy Olsen is senior editor at CT.