In this series

Americans are having a harder time trusting anyone these days—including pastors.

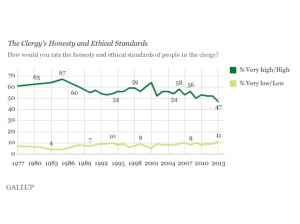

The country’s perception of clergy hit a new low in recent Gallup polling, with fewer than a third of Americans rating clergy as highly honest and ethical.

People are more likely to believe in the moral standards held by nurses, police officers, and chiropractors than their religious leaders. Clergy are still more trusted than politicians, lawyers, and journalists.

The continued drop in pastors’ reputation—down from 40 percent to 32 percent over the past four years—corresponds with more skepticism toward professions (and institutions) across the board.

Americans are also less likely than ever to know a pastor, with fewer than half belonging to a church and a growing cohort who don’t identify with a faith at all.

“As American culture becomes increasingly pluralistic and post-Christian, we can’t assume that Americans in general default to a positive view of clergy,” said Nathan Finn, executive director of the Institute for Transformational Leadership at North Greenville University. “Ministers must work harder to gain public trust than was the case even a generation ago.”

Finn also pointed out how scandals like clergy sex abuse, growing political polarization, and evangelicals’ countercultural moral positions can contribute to the decline in credibility among clergy, “especially among those who have either had bad church experiences or whose worldview assumptions are already at odds with historic Christian beliefs.”

The most dramatic decline in clergy trust came around the crisis of sex abuse by Catholic priests in the early 2000s, when positive ratings fell from 64 percent to 52 percent. They’ve steadily declined since.

Gallup found that white, high-income, and college-educated Americans thought best of pastors. The ratings were about the same across political parties, with 38 percent of Republicans and 36 percent of Democrats seeing high levels of honesty and ethical standards among clergy.

Views of pastors did vary by generation. Elder millennials and Gen X were most cynical; fewer than a quarter of people between ages 35 and 54 had a positive view of clergy ethics, compared to 38 percent of older Americans and 30 percent of those under 35. Positive perception of clergy among young people jumped by 10 percentage points compared to 2022.

Previous polling has shown that people tend to trust their own pastor more than pastors overall. According to Barna research, nearly two-thirds of Americans have a “very positive” opinion of a pastor they have a personal connection with, compared to a quarter who said the same about pastors in general.

But even that discrepancy has the potential to erode trust on the local church level.

“It may be that people are thinking, ‘I trust my pastor but not the ones I see on social media.’ However, sooner or later this drop will influence local decisions. For example, if a senior pastor has a conflict with the governing board, people may more quickly say, ‘Well, our pastor is just like those other pastors,’” said David Fletcher, founder of XPastor, a resource for executive pastors.

“Changes in societal views can influence church members and leaders beneath the surface—it is like the tide, carrying us along for quite some time before we realize we have moved.”

Even though public trust is slipping across professions—groups like doctors, pharmacists, and bankers saw slightly bigger declines than clergy—Christians still want to see pastors held to a higher standard.

“Scripture charges Christians in general and pastors in particular to be concerned about their reputation with the outside world,” said pastor Aaron Menikoff, author of Character Matters, a book focusing on the fruit of the Spirit in church leadership.

Menikoff cited 1 Timothy 3:7, where the qualifications of an elder include “a good reputation with outsiders,” and 1 Peter 2:12, which urges Christians to live “good lives” so that those outside the church notice their “good deeds.”

Evangelical leaders agreed certain church stances and doctrines may cause pastors to lose credibility in today’s culture, but that pastors should take their character and public witness seriously.

“Pastors will fall short, they are works in progress too. Nonetheless, by God’s grace they ought to strive for that holiness without which no one will see the Lord (Heb. 12:14),” said Menikoff, whose Atlanta-area church hosts an annual pastors’ conference called Feed My Sheep.

Glenn Packiam pointed to the need for pastoral humility and a rethinking of authority as he explored Barna research on the declining trust in pastors in his 2022 book The Resilient Pastor. He wrote:

I am less interested in finding ways to regain our credibility than I am in our willingness to take responsibility for why we’ve lost it. … From small country churches to uber-megachurches, many pastors have been found to be bullies and hypocrites, alcohol abusers, and womanizers. The crisis of credibility is a symptom. The misuse of authority is the root cause.

In the wake of public scandals involving pastors, ministries are developing accountability and discipleship training for pastors. For example, a free workshop through XPastor (involving CT partner publication Church Law & Tax) focused on legal, financial, and sexual standards as well as challenges around Sabbath rest, with the hope that setting church integrity “guardrails” can keep leaders on track.

Also important, said Finn, is how pastors respond when things go wrong: “It is within the power of church leaders to rebuild at least some trust if we respond faithfully to our own moral failures.”