It’s October 31 in Denver. Snow is falling. A cutting wind makes the air feel much colder than it is. But nothing will stop Jake Boston, a Gen Z Episcopalian, from celebrating the holiday.

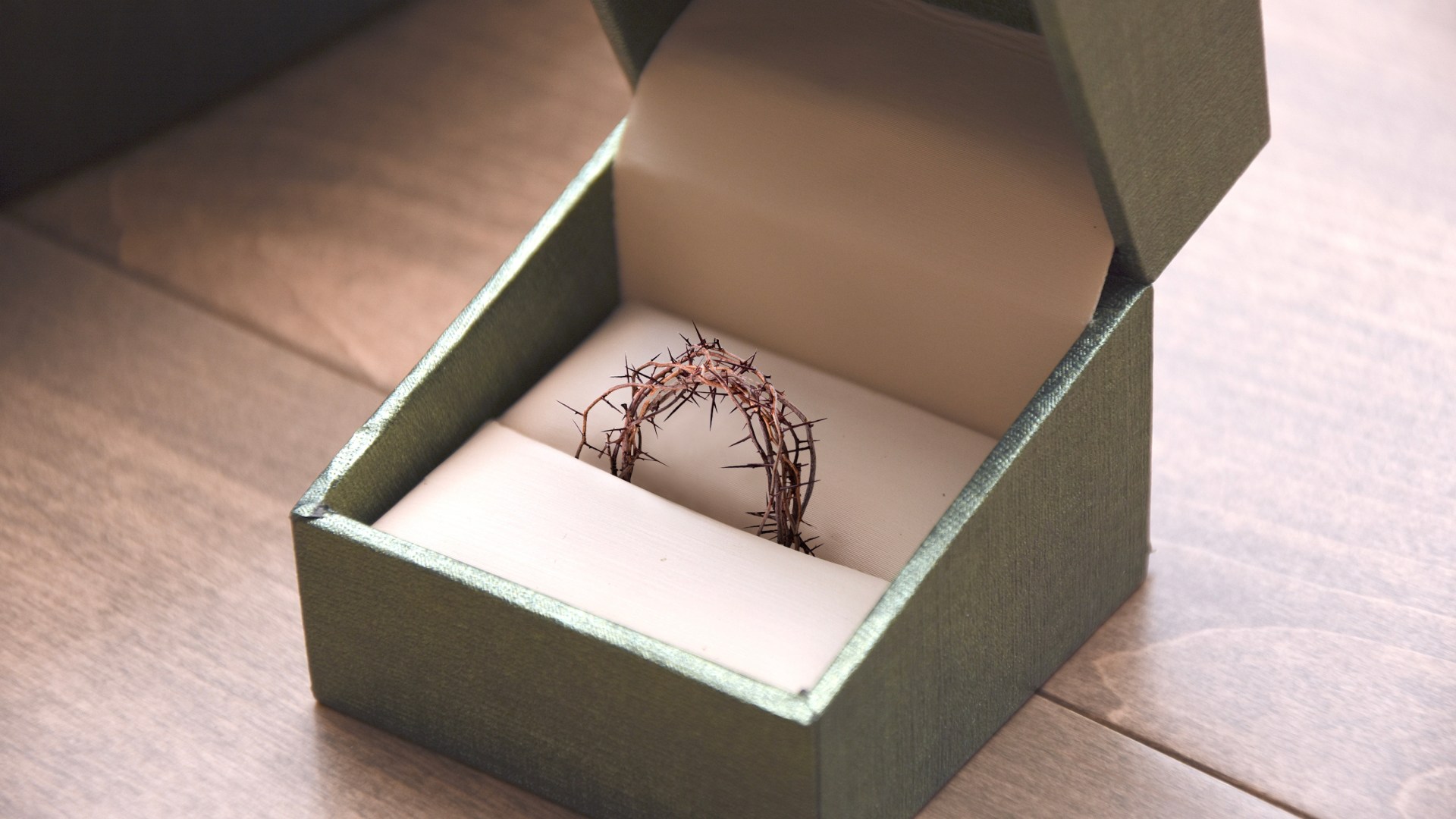

No, not Halloween—Reformation Day, when Protestants remember Martin Luther’s courageous choice to post his 95 Theses critiquing the Catholic church and launching the Reformation. Jake is reenacting that old story by tramping through the Colorado snow from mainline church to mainline church—60 in total—to post his own theses on their doors.

The lists, tailored to the seven American mainline denominations, critique their drift from orthodoxy into theological liberalism, challenging them to reaffirm the Resurrection, the divinity of Jesus, the authority of the Bible, and much more besides.

And Jake was not alone. A group of 1,000 Gen Z mainliners committed to their historic denominations—part of a grassroots group called Operation Reconquista—were working across the country to do the exact same thing. By the end of Reformation Day, they claim, they’d mailed, emailed, or physically posted their 95 theses to every mainline church in the United States, all without funding or a full-time organizer.

When I first heard about this operation, I admit I was both intrigued and worried. On the one hand, the past year has seen a surprising number of Gen Z–led spiritual renewals, most famously the Asbury revival. Maybe this was a similarly hopeful development?

On the other hand, their branding use of sordid military history was reminiscent of the “manosphere,” a highly online movement capturing the imagination of many young conservative men. (“Reconquista” is a nod to the Christian reconquest of the Iberian peninsula from Muslim kingdoms, whom Christian Europeans commonly called Moors, and the group’s website uses martial language and imagery.) Like many manosphere influencers, Reconquista first got traction online, largely through a YouTube channel run by a young man who goes by the digital pseudonym Redeemed Zoomer, as well as a Discord server.

Redeemed Zoomer creates lo-fi explainer videos—with Comic Sans font and what he describes as “derpy” graphics—about Christian theology and denominations, some of which have racked up millions of views. When he’s not explaining history or ideas, he’s talking about mainline institutional renewal as he creates cathedral-centered cities in the world-building video game Minecraft.

Despite these superficial similarities between Reconquista and the manosphere, the substance is radically different. Redeemed Zoomer and his fellow activists aren’t interested in “going their own way,” accelerationist politics, or “trad LARPers”—as Zoomer put it in an interview on my podcast—who spend more time burning institutions down than rebuilding them.

Their interest is institutional renewal in the mainline church, and their method—as detailed in a video explaining their Reformation Day activism—is calling young, theologically conservative Christians to reform and revive the denominations that their Christian forebears sweat and bled to build. Beyond the Reformation Day event, this primarily looks like mapping theologically conservative mainline congregations and encouraging Gen Z peers to join and serve in those communities.

To that end, Zoomer continually reminds his audience that their enemies aren’t people; they’re the principalities and powers of darkness (Eph. 6:12). Even when he’s critical of progressive Christians, he’s never crass or vitriolic. In fact, he explicitly asks those watching his channel not to harass or attack the people he’s critiquing.

When I asked Zoomer if allusions to violent conquests might lead the group astray, he noted that the Bible, too, uses military metaphors for the life of faith (e.g., Eph. 6, Phil. 2:25, 2 Tim. 2:3). He hopes Reconquista will channel youthful energy, which may otherwise be spent on vacuous or outright noxious pugilism, toward noble ends.

As a safeguard, the group has invited older mainline pastors to join Reconquista, and members are encouraged to rise above the fistic fray, season their speech with love, and challenge each other when they fail to meet these goals. Reconquista wants to be characterized by love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control, Redeemed Zoomer told me, not by the belligerent neo-pagan Twitter dunking of Andrew Tate wannabes.

Reconquista also rejects the racialized ugliness common in the manosphere and very online corners of the political Right. While their 95 theses to the Presbyterian Church (USA) state that “theology should not be done through a critical theory lens”—a sentiment I share, with some nuance—they also clearly anathematize racism and emphasize the importance of listening to the Global South. “The Mainline Church globally claims to want to elevate non-white voices,” one thesis says, “yet ignores the cries of repentance for theological liberalism coming from Church bodies in Africa and Asia, as is happening in the Anglican and Methodist communions.”

By contrasting Reconquista with the manosphere, I don’t mean to imply that it’s entirely male. The Episcopalian wing, which Redeemed Zoomer reports has seen the most success, is led by a young woman. But the group’s members are mostly young men, and Zoomer argues this is an asset in a time when—as is increasingly recognized even outside the church—young men are adrift in a predominantly progressive culture with no positive vision for masculinity and desperate to be connected to a mission that gives their lives purpose.

Progressive mainliners love to argue that progressive theology is the only way to make Christianity that mission for a young and progressive generation, Redeemed Zoomer says. But, speaking from experience, he disagrees, arguing that churches that liberalize to the point of abandoning orthodoxy have nothing distinctive to offer Gen Z.

Unchurched Gen Zers don’t need to go to a stodgy sanctuary to learn how to fly the rainbow flag. They can get that anywhere—without giving up Sunday mornings. To attract young people, and especially young men, the church must point Gen Z toward a divinely inspired, ancient purpose the secular world can’t offer: living for Jesus.

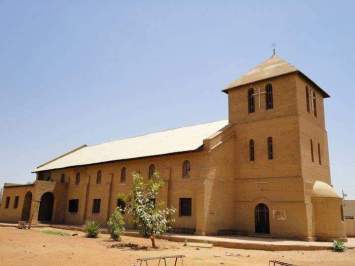

This is exactly what Zoomer experienced at age 14. Until his conversion, he says, he was a “secular leftist,” but at a small music camp led by a PCUSA professor, he encountered the beauty of Jesus through friendship, service to the poor, hymnody, and beautiful church architecture. The aesthetics of traditional churches weren’t merely a vibe for him—they became a window into the truth, goodness, and glory of the gospel.

Returning to his home in New York City, he found life by rooting himself in the Presbyterian tradition, singing hymns, studying the confessions, and taking the sacraments. This is the best way to integrate Gen Z men, like himself, into church life, he contends: engaging them in institutional construction.

He’s right. Gen X was cynical about institutions. Millennials, my own generation, deconstructed them. Gen Z may be the first generation to turn the tide, to renew, reform, and recover what past generations built.

Churches who build their congregation on critique—by perpetually deconstructing and disavowing the past or endlessly dunking on institutional leaders for not being “based” enough—will not survive and flourish long-term. Reformers like Luther did not only criticize; they also built.

If we want to see Gen Z—the most unchurched, secular generation in American history—join in the life of the church, we must actively involve them in institution building. We must invite and integrate them into a community of belonging rooted in history, orthodoxy, and tradition. This is especially the case if we want young conservative men to do more than ape Tate, as Matthew Loftus recently argued at CT.

Of course, there will be legitimate critiques of movements like Reconquista. Is its militaristic branding a strength or a hindrance? Is it driven by theology and liturgy, or merely an aesthetic vibe? Why not break away from heretical institutions that have already proven immune to reformation, as Luther himself did? Is this simply nostalgia for a golden age that never existed?

While these are important questions—and members of Reconquista have addressed many of them—they risk missing the lede: God’s Spirit is at work in Gen Z in surprising, beautiful, and encouraging ways.

They deserve our encouragement in turn. Left- and right-wing deconstructors will do their worst to distract these young builders from the labor at hand. My hope is that they will take up Nehemiah’s cry: “I am carrying on a great project and cannot go down” (Neh. 6:3).

Don’t come down, Gen Z. Build something that will last.

Patrick Miller is a pastor at The Crossing in Columbia, Missouri. He’s also the co-author of Truth Over Tribe: Pledging Allegiance to the Lamb, Not the Donkey or the Elephant, and the co-host of the cultural commentary podcast Truth Over Tribe.