As an Asian woman, I stick out in this train,” our global staff writer Sophia Lee tweeted this past December. “A concerned elderly woman with red lipstick approached me. We had language problems but I think she was trying to make sure I knew where I was going, because she kept pointing to our train and repeating, ‘Kyiv!’”

Sophia was traveling into Ukraine to meet with pastors in cities like Kherson, Vorzel, Irpin, and Kyiv. Though I rarely engage with Twitter, I found myself repeatedly checking for more of Sophia’s tweets as our staff prayed for her and her interviewees during each stage of her journey.

“We’ve crossed into Ukraine. They shut off all the lights in the train so that the Russians cannot target us,” Sophia wrote. “This is the first time I’ve viscerally felt the presence of war. Feels surreal, sitting in darkness, listening to the creak and clang of the train.” She described passing by war-ravaged homes in frigid conditions without power or heat, writing, “my heart clenches” as she thought of elderly Ukrainians who “either cannot or will not leave their homes.”

Throughout her reporting trip, Sophia posted stories of sorrow, terror, and brutality—as well as vibrant ministry, zealous prayers, and baptisms of new believers. “Ministers in Ukraine Are ‘Ready to Meet God at Any Moment’” details several of these accounts, along with photographs from Joel Carillet.

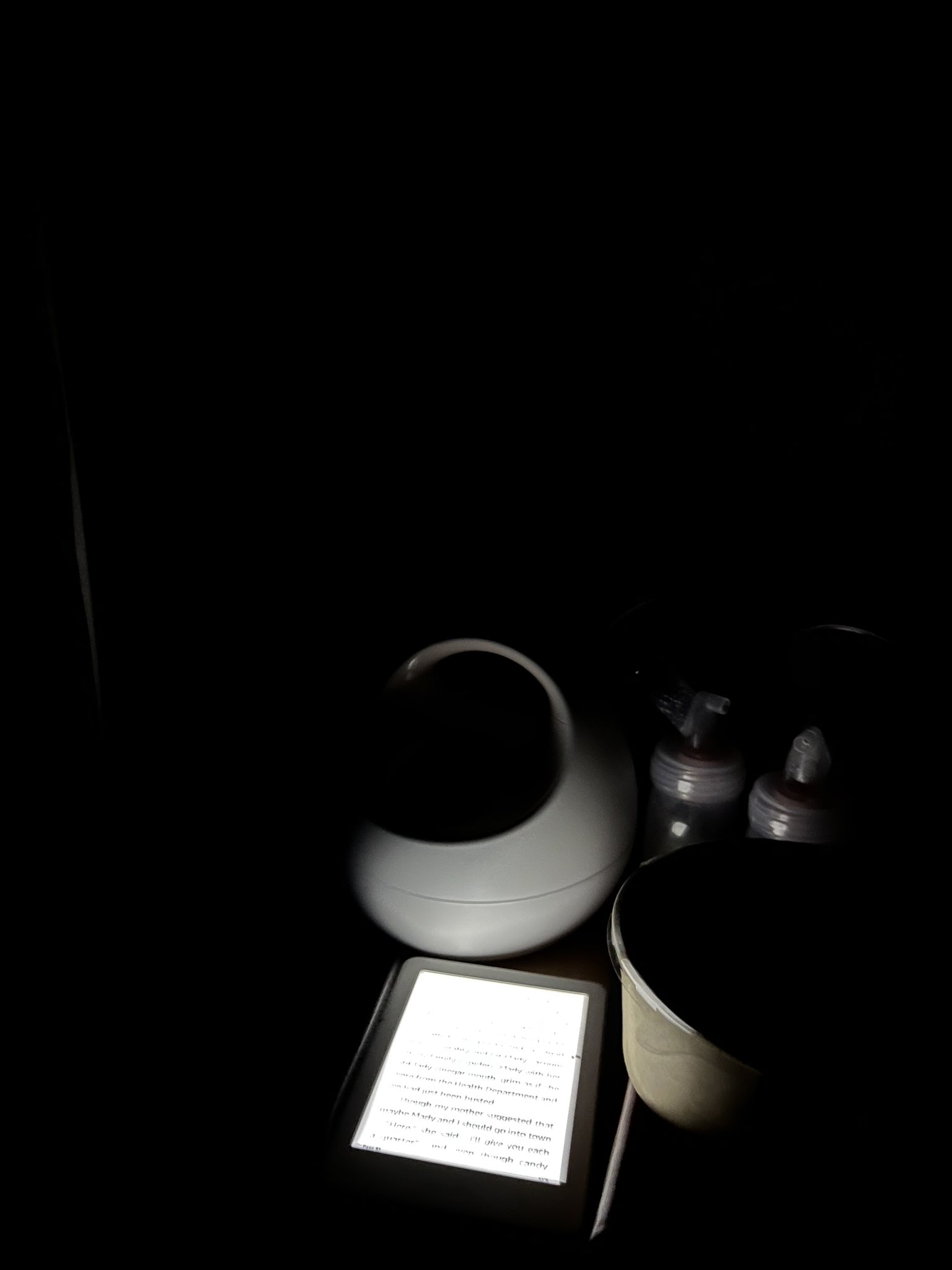

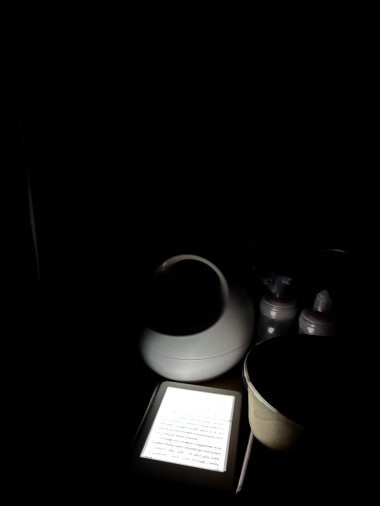

One picture, in particular, stands out to me: a nearly black image Sophia took from her seat within that darkened train car, illuminated only by the soft light of her Kindle. “Outside & inside, it’s pitch dark,” she wrote. “The only glow of light is from our devices.” That simple image captures the essence of what she was traveling to report on: the light of the church shining amid darkness.

Sophia Lee

Sophia LeeWhile their reality ought not to be sentimentalized—these Ukrainian believers are carrying a tremendous burden of trauma and grief, and they continue to face severe, ongoing danger—their testimony challenges us. Daily, they’re grappling with a question that for many of us feels merely hypothetical: How would I minister if any day, any moment, could be my last?

Yet, as God teaches us to “number our days” (Ps. 90:12), we see that any sense of that question being hypothetical is pure illusion. This question is in fact true for each of us, whether we live in a war zone or in much safer circumstances. The answer exemplified by many of these Ukrainian Christians is one of resilient faithfulness—relying on the Spirit to do the work of the church by loving their neighbors and proclaiming the Good News. Even in blackout conditions, they shine as a city on a hill.

Kelli B. Trujillo is print managing editor of Christianity Today.