This piece was adapted from Russell Moore’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

This past week’s bonus episode of CT’s The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill podcast featured a conversation between my colleague Mike Cosper and therapist Aundi Kolber about the effects spiritual trauma can have on one’s body.

The dialogue has haunted me ever since because it’s prompted me to ask whether American Christianity has experienced collectively how some experience trauma individually—and whether that might provoke us to consider what we are asking for when we pray for “revival.”

In the interview, Mike asked how someone who has experienced a spiritually toxic environment could begin to heal. Kolber—referencing work such as Bessel van der Kolk’s influential book The Body Keeps the Score—says she begins not with how a traumatized person thinks about a situation but, first, with what that person’s body is showing.

That’s because, she argues, we can numb our perception to realities that we don’t know how to make sense of. But, she says, the nervous system often points the way—signaling that something is wrong by manifesting a variety of symptoms, sometimes long before the mind is ready to acknowledge that there might be a problem.

It’s important to recognize this, Kolber says, and to not speed through healing from trauma. Often people want a checklist of ways to recover from a horrible situation—including spiritual abuse or trauma—so they can “move on” quickly with their lives.

But the path to healing is not so simple, she argues. It usually requires a slower, more deliberate attempt at grounding and sorting through what happened. This is important because, as Kolber puts it, “what is not repaired is repeated.”

How many of us have seen this dynamic at work in toxic family situations? Sometimes a person from a horrible background will seek out someone else—perhaps a spouse, a friend, or even a pastor—who carries out the very same sorts of abusive behavior.

Kolber suggests that is because we often default to what feels familiar. And those who haven’t yet confronted just how abnormal their past situations were might well repeat the same scenarios over and over—and never detect the warning signs.

This happens not just with families but with churches too.

Right before I listened to this episode, I had coffee with a pastor friend and colleague, Ray Ortlund, who referenced a line from A. W. Tozer that I had never heard before, a line that jarred me at first.

Tozer—one of the 20th century’s most respected evangelical advocates of a “deeper life” spirituality and of the necessity of revival—suggested that maybe the American church should stop seeking revival.

“A religion, even popular Christianity, could enjoy a boom altogether divorced from the transforming power of the Holy Spirit and so leave the church of the next generation worse off than it would have been if the boom had never occurred,” Tozer wrote in 1957.

“I believe that the imperative need of the day is not simply revival, but a radical reformation that will go to the root of our moral and spiritual maladies and deal with causes rather than with consequences, with the disease rather than with symptoms.”

“It is my considered opinion that under the present circumstances we do not want revival at all,” Tozer wrote. “A widespread revival of the kind of Christianity we know today in America might prove to be a moral tragedy from which we would not recover in a hundred years.”

This would not have surprised me had it come from the kind of antirevivalists I’ve encountered throughout the years—those for whom, it seems, every form of emotional experience is suspect in favor of doctrinal syllogisms and almost any mass evangelism efforts are suspected of being marketing or manipulation. But that wasn’t Tozer.

I was also taken aback because revival is precisely what I think the American church needs. The older I get, the more I can see the best gifts that a return to the evangelical revivalism of the past could offer the church.

To be sure, some of that is nostalgia. I grew up singing songs like “Revive Us Again” and “Send the Light” Sunday after Sunday, in a church that was not embarrassed to pray for revival (or to schedule revival meetings on the calendar, but that’s another story).

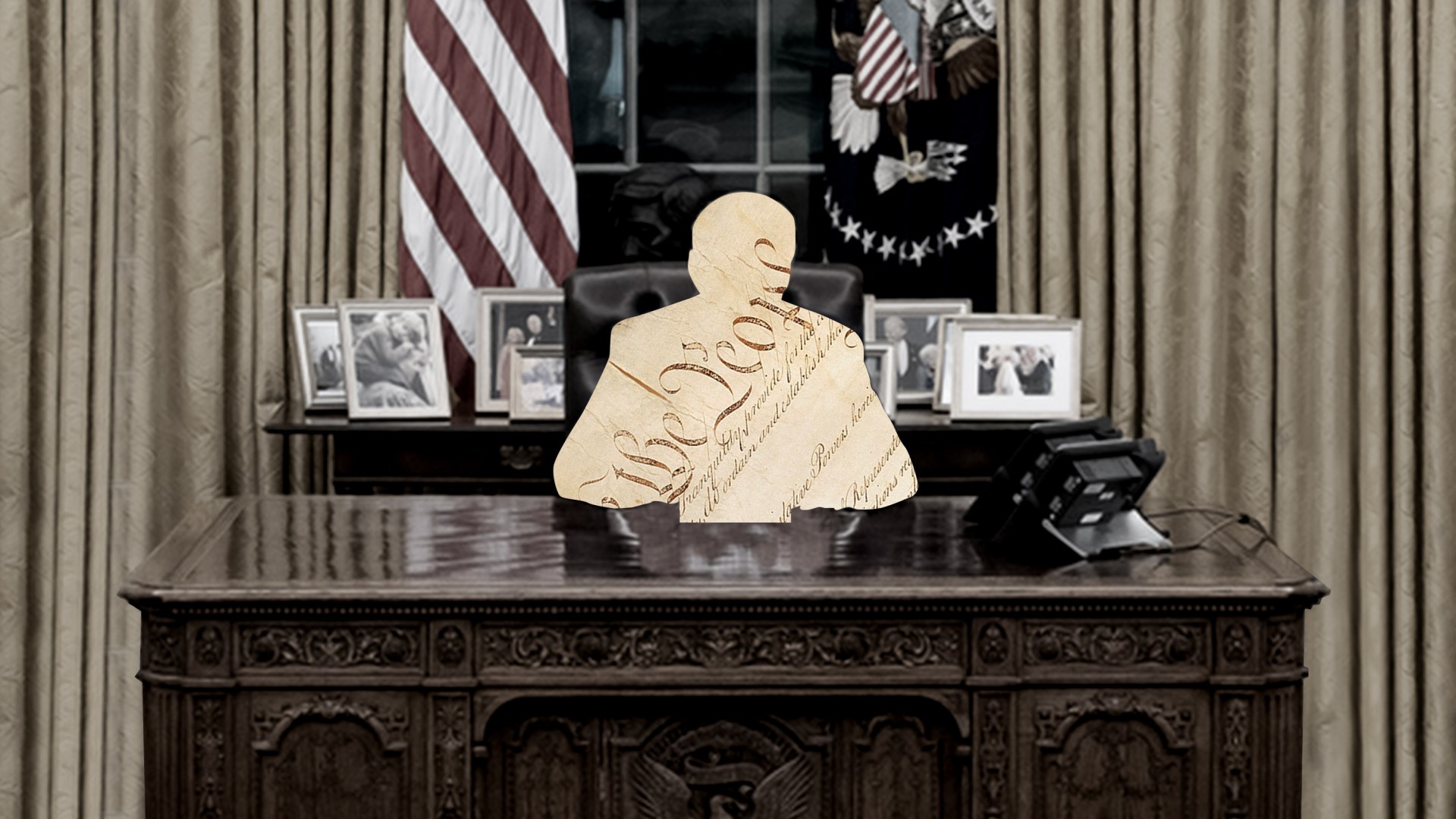

When we look at the wreckage that is American evangelical Christianity right now—the splintered churches and fractured friendships, the leadership scandals and revelations of abuse, the politicization and grievance-based identity politics, and the ambitious hackery often disguised as culture wars—is it not obvious that we need revival?

When we see people disgusted with and harmed by our very own churches, people who wonder whether there’s anything spiritually real, why on earth would we not hope for revival?

I believe we still should—but only a revival of the right kind.

To me, what Tozer was warning about seems oddly like the much more modern idea of trauma repetition. If by “revival” we mean is a resurgence of American Christianity—with all the numbers, influence, programs, and reputation the church once had—the results could indeed be catastrophic.

Jesus warned the religious leadership of his time: “Woe to you, teachers of the law and Pharisees, you hypocrites! You travel over land and sea to win a single convert, and when you have succeeded, you make them twice as much a child of hell as you are” (Matt. 23:15).

Jesus’ point—after laying bare the ways the religious leaders were lifelessly mimicking religion and exploiting the piety of their followers—was that “reviving” or expanding such lifelessness makes a terrible situation even worse.

In the Bible, revival is tied to the idea of resurrection—from the classic passage of the wind breathing life into the valley of dry bones (Ezek. 37) and onward.

But not everything that continues life is resurrection. God placed the fiery sword at the entrance of Eden to “guard the way to the tree of life” (Gen. 3:24) precisely because he did not want a twisted, fallen humanity to live forever in that state of death.

An undying humanity without spiritual life is not resurrection life, after all. It’s a zombie story—the corrupted and decayed body is animated and without an endpoint but still horrifically dead.

Many high school students have read the short story “The Monkey’s Paw,” about the wish for a dead loved one to be brought back to life. The terror comes about because that person is indeed made alive, but just as he is—a decomposing nightmare. The Bible points us to a Holy Spirit revival, not to a Monkey’s Paw revival.

In other words, the church needs revival, but only the kind that comes from the Spirit. And that will require that we honestly see just how much we’ve normalized things that are abnormal. Resurrection comes, but not unless what has passed away is buried (John 12:24).

If true revival—not just a resurgence of the status quo—does not come, we will end up repeating the things that have led us to our present crisis. We will end up as Jesus warned the church at Sardis: “You have a reputation of being alive, but you are dead” (Rev. 3:1).

Healing can and does come. Those who have lived through trauma shouldn’t believe the lie that they are irreparably “broken” and that all they can ever experience is reliving their trauma (or carrying it out on others).

As Kolber points out, those cycles and experiences can be replaced with life and health and a new start. But that can’t be done without paying attention to what has happened in the past—even if one’s body keeps the score when the mind cannot and the soul feels what the brain can’t process.

The same can happen for a church. But it does not involve doing the same things over again with a new cast of characters. Nor does it mean tossing everything aside and choosing the mirror image of the same problems, just from a reverse direction. It means, as Jesus said, that we should “wake up! Strengthen what remains and is about to die” (Rev. 3:2).

What is not repaired is repeated—and what is not reformed cannot be revived.

Russell Moore leads the Public Theology Project at Christianity Today.