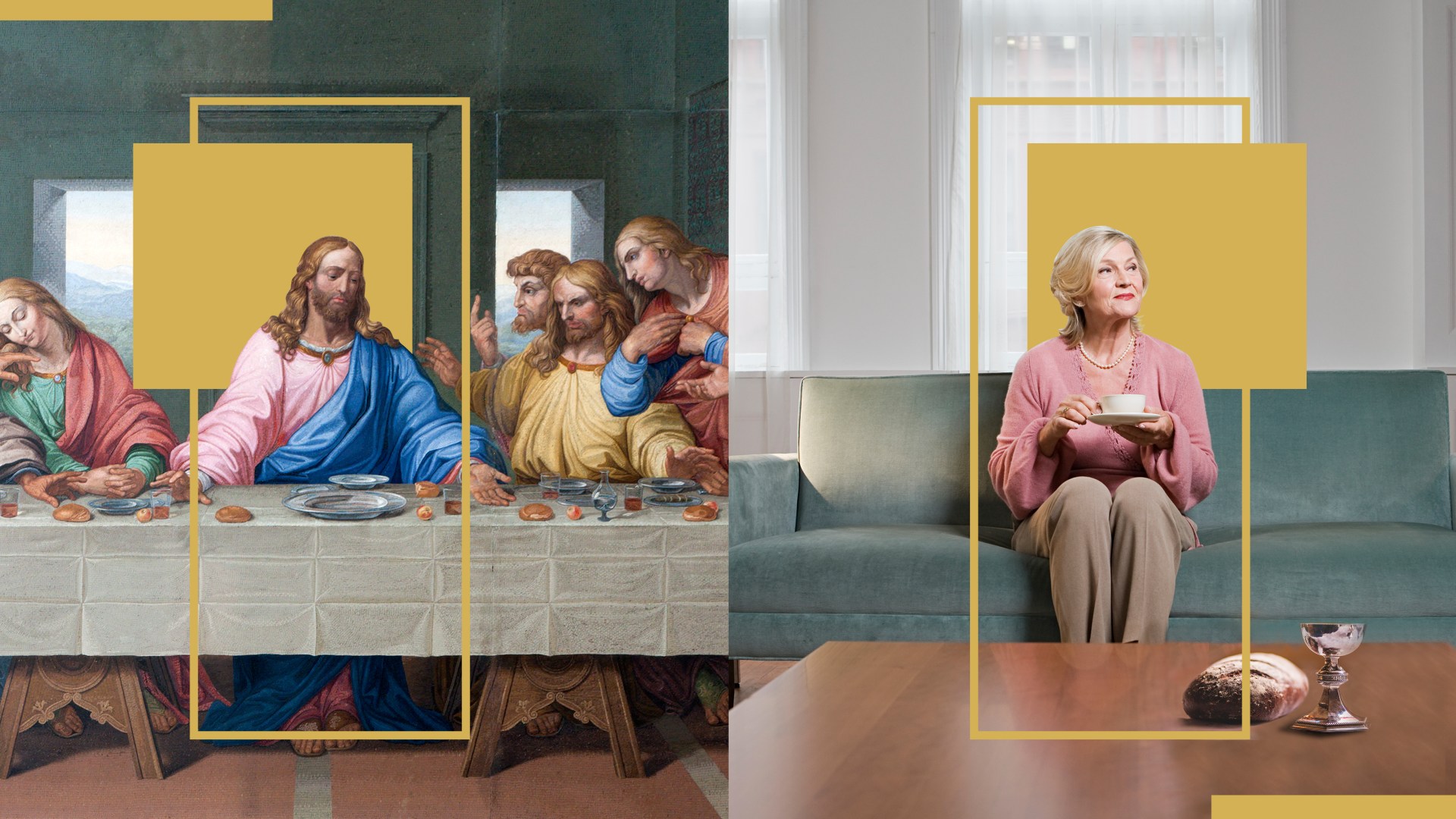

Practicing the liturgical calendar is like participating in immersive theater. Through fasting, feasting, rites, and rituals, we walk into the story of Jesus. In Advent, we lean into longing and wait together for the coming King. At Christmas, we lay babies in makeshift mangers and enter into the Incarnation. During Lent, we smear ashes on our foreheads and remember sin and death. All of it builds to the big moment: Easter Sunday.

For Christians, this is the World Series, the crescendo of the symphony, the climax of the play. This is what we’ve been sitting on the edge of our seats waiting for all year. But this year: nothing. The game is canceled in its final inning. The horn section left in the middle of the concerto. The theater caught fire in the third act.

As a priest, this feels incredibly unsatisfying. Sure, we’ll livestream services. The Word will be proclaimed. But it isn't the same. Something is clearly lost.

And yet, the solid fact remains that Christians do not make Easter through our worship and our calendar. Jesus rose from the dead, and even if it were never acknowledged en masse, it would remain the fixed point around which time itself turns. The truth of the Resurrection is wild and free. It possesses us more than we could ever possess it and rolls on happily with no need of us, never bending to our opinions of it. If the claims of Christianity are true, they are true with or without me. On any given day, my ardent belief or deep skepticism doesn’t alter reality one hair’s breadth.

Believers and skeptics alike often approach the Christian story as if its chief value is personal, subjective, and self-expressive. We come to faith primarily for how it comforts us or helps us cope or lends a sense of belonging. However subtly, we reduce the Resurrection to a symbol or a metaphor. Easter is merely an inspirational tradition, a celebration of rebirth and new life that calls us to the best version of ourselves and helps give meaning to our lives.

But the actualities that we now face in a global pandemic—the overwhelmed hospitals and morgues, the collapsing global economy, and the terrifying fragility of our lives—ought to put an end to any sentimentality about the Resurrection. To borrow the words of Flannery O’Connor, “If it’s a symbol, to hell with it.”

The stakes could not be higher. As a deadly virus speeds its way around the world bringing chaos, destruction, and death, it’s painfully clear that the Resurrection is either the whole hope of the world—the very center of reality—or Christianity is not worth our time.

“Let us not mock God with metaphor, analogy, sidestepping, transcendence; making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the faded credulity of earlier ages,” writes John Updike in his poem “Seven Stanzas at Easter.” If Jesus’ “cells’ dissolution did not reverse, the molecules reknit, the amino acids rekindle, the Church will fall.”

I am a Christian today not because it answers all my questions about the world or about our current suffering. It does not. And not because I think it is a nice, coherent moral order by which to live my life. And not because I grew up this way or have fond feelings about felt boards and hymn sings. And not because it motivates justice or helps me to know how to vote. I am a Christian because I believe in the Resurrection. If it isn’t true, to hell with it.

On the other hand, if Jesus did in fact come back from the dead on a quiet Sunday morning some 2,000 years ago, then everything is changed—our beliefs, our ethics, our politics, our time, our relationships. If it is true, then the resurrection of Jesus is the most determinative fact of the universe, the center point of history. The Resurrection is ultimately truer and more lasting than death or destruction, violence or viruses. It’s truer, too, than our celebration of it, however beautiful, however meager.

That morning in history when Jesus rose, there was no expectation of a resurrection. There was no fanfare. No churches gathering with songs of triumph, no bells ringing, nothing. A few women went out to tend to Jesus’ dead body. His “nobody” disciples were laying low, lost in grief and feeling afraid. The rest of Jerusalem and the wider world had moved on. The sun rose. People went about their business gathering grain and water from wells. They started breakfast.

All of the cosmos was changed, and it was almost entirely overlooked.

This coming Sunday will be quiet too. Nearly 80 percent of Americans are under stay-at-home orders and will continue to be for most of the 50 days of Eastertide. But, in the end, what made Easter morning matter was never the packed sanctuaries, never the hymns or celebrations, rituals or rites. Just as the quietness of that first Easter did not determine if the stone rolled away or not, the locked doors of our local churches don’t determine it either.

The truest fact of the universe this Eastertide is not death tolls, emptied sanctuaries, or overcrowded hospitals. The truest fact of the universe is an empty tomb. The Resurrection is the only evidence that love triumphs over death, weakness prevails over strength, and beauty outlives ashes. If Jesus is risen in actual history, with all the palpability of flesh, fingers, bone, and blood, there is hope that our mourning will be comforted and that death will not have the final word.

Tish Harrison Warren is a priest in the Anglican Church in North America, a member of The Pelican Project, and a writer in residence at Church of the Ascension in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She is the author of Liturgy of the Ordinary and a contributor to the forthcoming book Uncommon Ground: Living Faithfully in a World of Difference.

Want to read or share this in Korean? Now you can!CT also offers 20 prayers to pray during this pandemic, in English, Spanish, Portuguese, French, Korean, and Chinese (simplified and traditional).For translations of other select CT coronavirus articles, click here and look for the yellow links.