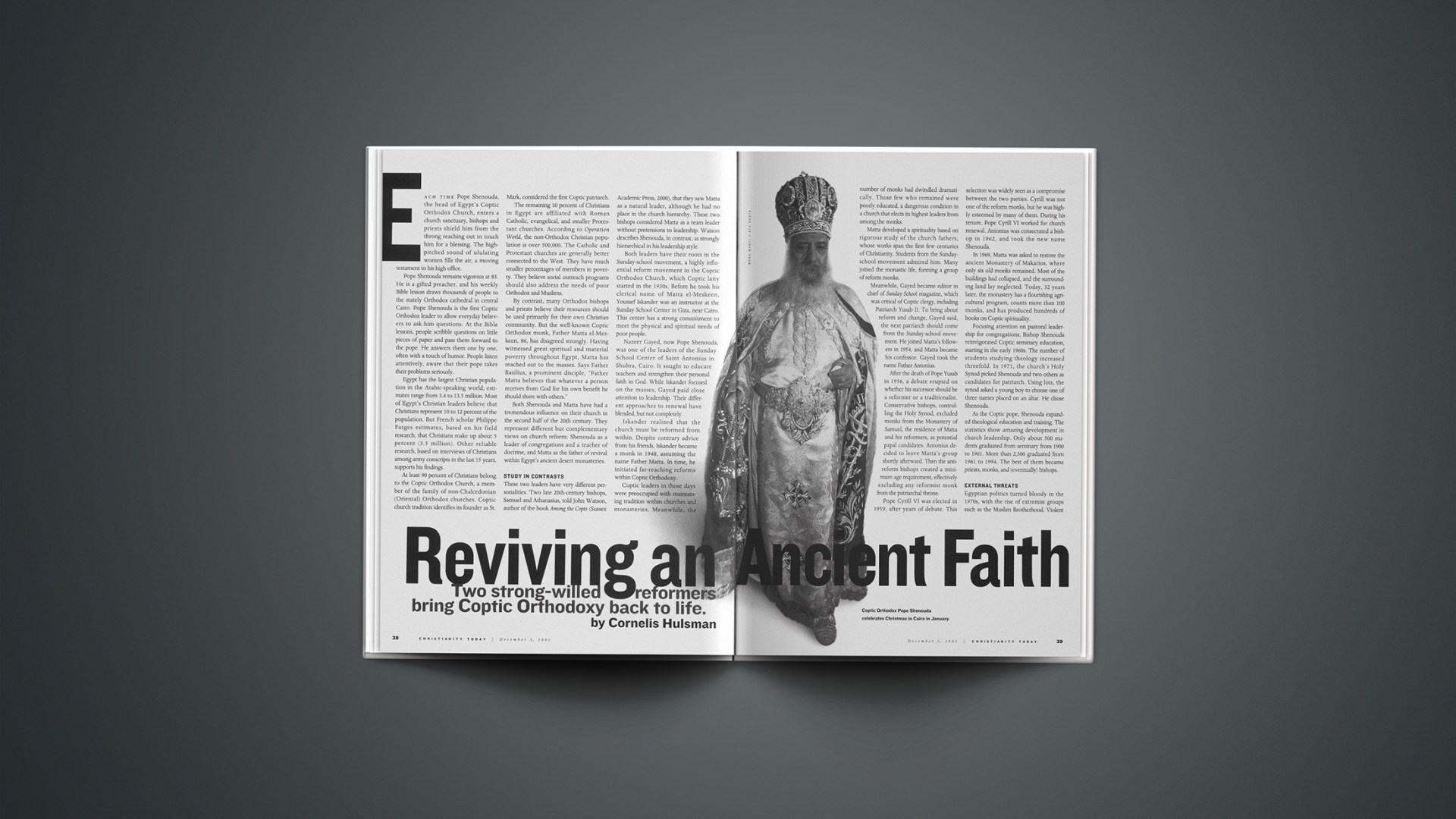

Each time Pope Shenouda, the head of Egypt’s Coptic Orthodox Church, enters a church sanctuary, bishops and priests shield him from the throng reaching out to touch him for a blessing. The high-pitched sound of ululating women fills the air, a moving testament to his high office.

Pope Shenouda remains vigorous at 83. He is a gifted preacher, and his weekly Bible lesson draws thousands of people to the stately Orthodox cathedral in central Cairo. Pope Shenouda is the first Coptic Orthodox leader to allow everyday believers to ask him questions. At the Bible lessons, people scribble questions on little pieces of paper and pass them forward to the pope. He answers them one by one, often with a touch of humor. People listen attentively, aware that their pope takes their problems seriously.

Egypt has the largest Christian population in the Arabic-speaking world; estimates range from 3.4 to 13.5 million. Most of Egypt’s Christian leaders believe that Christians represent 10 to 12 percent of the population. But French scholar Philippe Farges estimates, based on his field research, that Christians make up about 5 percent (3.5 million). Other reliable research, based on interviews of Christians among army conscripts in the last 15 years, supports his findings.

At least 90 percent of Christians belong to the Coptic Orthodox Church, a member of the family of non-Chalcedonian (Oriental) Orthodox churches. Coptic church tradition identifies its founder as St. Mark, considered the first Coptic patriarch.

The remaining 10 percent of Christians in Egypt are affiliated with Roman Catholic, evangelical, and smaller Protestant churches. According to Operation World, the non-Orthodox Christian population is over 500,000. The Catholic and Protestant churches are generally better connected to the West. They have much smaller percentages of members in poverty. They believe social outreach programs should also address the needs of poor Orthodox and Muslims.

By contrast, many Orthodox bishops and priests believe their resources should be used primarily for their own Christian community. But the well-known Coptic Orthodox monk, Father Matta el-Meskeen, 86, has disagreed strongly. Having witnessed great spiritual and material poverty throughout Egypt, Matta has reached out to the masses. Says Father Basilius, a prominent disciple, “Father Matta believes that whatever a person receives from God for his own benefit he should share with others.”

Study in Contrasts

Both Shenouda and Matta have had a tremendous influence on their church in the second half of the 20th century. They represent different but complementary views on church reform: Shenouda as a leader of congregations and a teacher of doctrine, and Matta as the father of revival within Egypt’s ancient desert monasteries.

These two leaders have very different personalities. Two late 20th-century bishops, Samuel and Athanasius, told John Watson, author of the book Among the Copts (Sussex Academic Press, 2000), that they saw Matta as a natural leader, although he had no place in the church hierarchy. These two bishops considered Matta as a team leader without pretensions to leadership. Watson describes Shenouda, in contrast, as strongly hierarchical in his leadership style.

Both leaders have their roots in the Sunday-school movement, a highly influential reform movement in the Coptic Orthodox Church, which Coptic laity started in the 1930s. Before he took his clerical name of Matta el-Meskeen, Youssef Iskander was an instructor at the Sunday School Center in Giza, near Cairo. This center has a strong commitment to meet the physical and spiritual needs of poor people.

Nazeer Gayed, now Pope Shenouda, was one of the leaders of the Sunday School Center of Saint Antonius in Shubra, Cairo. It sought to educate teachers and strengthen their personal faith in God. While Iskander focused on the masses, Gayed paid close attention to leadership. Their different approaches to renewal have blended, but not completely.

Iskander realized that the church must be reformed from within. Despite contrary advice from his friends, Iskander became a monk in 1948, assuming the name Father Matta. In time, he initiated far-reaching reforms within Coptic Orthodoxy.

Coptic leaders in those days were preoccupied with maintaining tradition within churches and monasteries. Meanwhile, the number of monks had dwindled dramatically. Those few who remained were poorly educated, a dangerous condition in a church that elects its highest leaders from among the monks.

Matta developed a spirituality based on rigorous study of the church fathers, whose works span the first few centuries of Christianity. Students from the Sunday-school movement admired him. Many joined the monastic life, forming a group of reform monks.

Meanwhile, Gayed became editor in chief of Sunday School magazine, which was critical of Coptic clergy, including Patriarch Yusab II. To bring about reform and change, Gayed said, the next patriarch should come from the Sunday-school movement. He joined Matta’s followers in 1954, and Matta became his confessor. Gayed took the name Father Antonius.

After the death of Pope Yusab in 1956, a debate erupted on whether his successor should be a reformer or a traditionalist. Conservative bishops, controlling the Holy Synod, excluded monks from the Monastery of Samuel, the residence of Matta and his reformers, as potential papal candidates. Antonius decided to leave Matta’s group shortly afterward. Then the anti-reform bishops created a minimum age requirement, effectively excluding any reformist monk from the patriarchal throne.

Pope Cyrill VI was elected in 1959, after years of debate. This selection was widely seen as a compromise between the two parties. Cyrill was not one of the reform monks, but he was highly esteemed by many of them. During his tenure, Pope Cyrill VI worked for church renewal. Antonius was consecrated a bishop in 1962, and took the new name Shenouda.

In 1969, Matta was asked to restore the ancient Monastery of Makarios, where only six old monks remained. Most of the buildings had collapsed, and the surrounding land lay neglected. Today, 32 years later, the monastery has a flourishing agricultural program, counts more than 100 monks, and has produced hundreds of books on Coptic spirituality.

Focusing attention on pastoral leadership for congregations, Bishop Shenouda reinvigorated Coptic seminary education, starting in the early 1960s. The number of students studying theology increased threefold. In 1971, the church’s Holy Synod picked Shenouda and two others as candidates for patriarch. Using lots, the synod asked a young boy to choose one of three names placed on an altar. He chose Shenouda.

External Threats

As the Coptic pope, Shenouda expanded theological education and training. The statistics show amazing development in church leadership. Only about 500 students graduated from seminary from 1900 to 1961. More than 2,300 graduated from 1961 to 1994. The best of them became priests, monks, and (eventually) bishops.

Egyptian politics turned bloody in the 1970s, with the rise of extremist groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood. Violent outbreaks between Muslims and Christians became common. Anwar Sadat, who became president in 1970, was under heavy pressure to designate Shari’ah, the Islamic legal code, as the source for constitutional law. Shenouda became a public opponent of designating Shari’ah as such. He also publicly protested government policies restricting new church construction.

Religious tensions grew worse. In September 1981, Sadat placed the pope under house arrest along with scores of Muslim and Christian leaders. A committee of five bishops replaced the pope. Watson, serving at the time as a representative of the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury, advocated the immediate release of Pope Shenouda. But, as Watson told ct, many Coptic intellectuals and clergy “publicly blamed Pope Shenouda for inflaming tensions with his high-profile protests against injustices.”

Bishop Marcos, a member of the ruling Holy Synod since 1978, denies that clergy publicly criticized the pope. “The first meeting of the Holy Synod after September 1981 decided that the authority of the pope is not to be challenged,” he says, “but cooperation with the papal committee was needed to keep the church in peace.”

Father Matta was still more blunt in a rare interview with Time magazine in September 1981. “Shenouda’s appointment was the beginning of the trouble,” he said. “The mind replaced inspiration, and planning replaced prayer. … For the first years I prayed for him, but I see the church is going from bad to worse because of his behavior. … I can’t say I’m happy. But I am at peace now. Every morning, I was expecting news of more bloody collisions. Sadat’s actions protect the church and the Copts. They are from God.”

Many Copts believe that Shenouda has never forgiven Matta for these words. The interview appeared only days before Islamic militants assassinated Sadat during a military parade on October 6, 1981. Bishop Samuel, chairman of the papal committee, was also killed in the attack.

In the aftermath, top leaders in the Coptic church pressed for Shenouda to be sidelined. But pro-Shenouda groups came to his defense, including the U.S.-based American Coptic Association. Shenouda remained under arrest at the Bishoi monastery for another 39 months. When authorities released him, Shenouda returned to Cairo on Coptic Christmas, January 1985. But he was taken by surprise that some of his own clergy had turned against him.

Thereafter, Shenouda referred to Matta as “the rebellious monk.” According to Marcos, the pope and the Holy Synod differ with Matta on theology. Many observers believe the pope resents Matta’s opinions about his leadership.

The internal differences are not limited to Shenouda and Matta. The Egyptian press frequently reports many other intrachurch differences. Issues often arise over the pope’s authority. Pope Shenouda once described himself as the father of the church. Just as children have to obey their father, he explained, so the children of the church have to obey him. Many do. But not all.

Shenouda’s influence has been dominant since 1985. The balance has tilted in the direction of his style of church government. Religion scholar Wolfram Reiss, whose research on Coptic reform was published in the German journal Studies in Oriental Church History, believes Shenouda’s greatest influence on the church is in nominating so many new bishops and creating new dioceses.

Shenouda often subdivides a diocese into smaller parts after its bishop dies. Bishops, in Shenouda’s view, should be closer to the priests and believers. Some dioceses, such as in the Sinai, are extremely small. But Reiss concluded, “The bishops prior to 1971 all represented large bishoprics, which gave them strength and influence. A larger number of bishops in smaller bishoprics increases the power of the patriarch to an extent no patriarch has enjoyed in centuries.”

Matta has withdrawn to his monastery in recent decades, but his books still have a potent influence even though his books have not been sold in Coptic Orthodox bookstores in Egypt since 1985. No bishops have been selected from his monastery since 1971. Still, Matta’s monastic revival has introduced a new generation to ancient Coptic monastic disciplines.

The followers of Matta and Shenouda are likely to struggle anew when Shenouda dies. The vitality of Coptic Orthodoxy may depend on whether the legacy of Father Matta and Pope Shenouda is conflict or cooperation between the church’s bishops and monks.

Copyright © 2001 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere

Also appearing on our site today:

Welcoming the Uninvited Savior | When the Holy Family fled Bethlehem, Herod’s evil became a blessing for Egypt.

For more information about the Coptic church, see Coptic.net

The official site of Pope Shenouda houses articles by the pope, news, and a photo gallery.

Last year, the Detroit News covered local Coptic celebrations of the second millennium anniversary of Jesus’ visit to Egypt.

In 1997, Cornelis Hulsman and Timothy C. Morgan reported on Egypt’s Coptic church thriving in the face of bloody carnage, legal restraint, and discrimination.

For more Christianity Today coverage of Egypt, see our world report.