In this series

Pastor James MacDonald and Harvest Bible Chapel filed a lawsuit this month against two ex-members and former Moody Radio host Julie Roys, accusing them of spreading false information about the Chicago-area megachurch’s financial health and leadership.

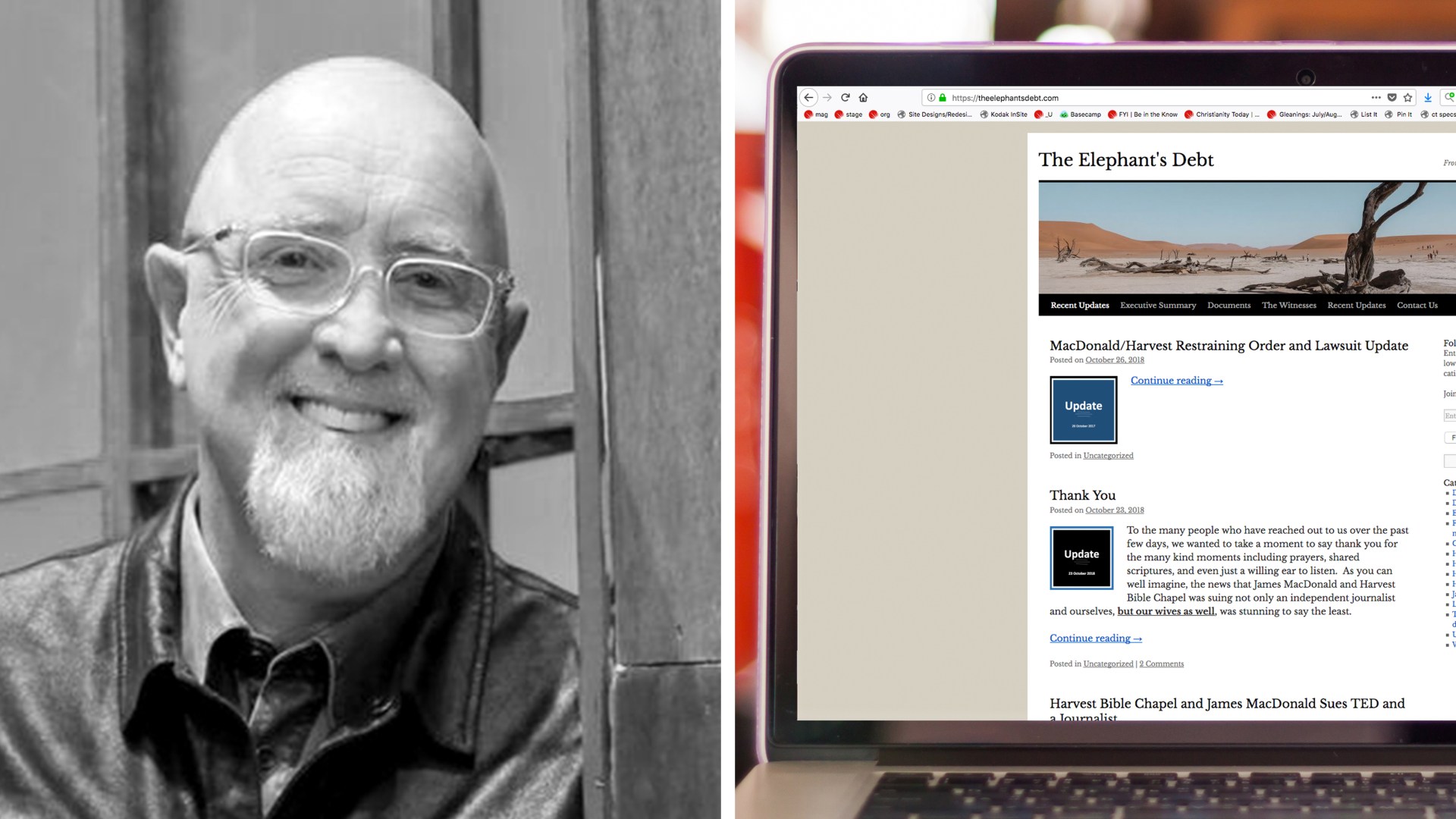

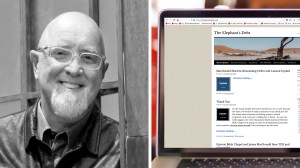

The main targets of the church’s defamation complaint are Ryan Mahoney and Scott Bryant, who together run the blog The Elephant’s Debt. The site has culled stories of alleged mismanagement at Harvest since 2012, including claims of as much as $70 million in mortgage debt and a lack of accountability from its elder board.

Harvest has addressed some of the criticisms. MacDonald, its founder and senior pastor, apologized in 2014 to a trio of former elders who were disciplined for speaking out about a “culture of fear and intimidation.”

But the church challenges the blog’s characterizations of its financial standing and MacDonald’s character, wealth, and leadership. The lawsuit lists more than 57 points of disagreement with details published on The Elephant’s Debt.

Leaders at Harvest said the blog harmed its reputation enough that 2,000 people left the congregation in 2013. The multi-site church numbers 13,000 attendees across seven locations, making it one of the biggest in Illinois.

“Our goal was to end their prolonged and divisive effort to undermine the Elder governance of our church and to discredit our primary leaders,” elders said in a statement to their congregation this month. “We have chosen to accomplish that by filing a civil suit in Cook County.”

Mahoney, a former teacher at Harvest Christian Academy, and Bryant left the church in 2010. They posted the bulk of their updates on The Elephant’s Debt between 2012 and 2013, including testimonies from more than a dozen former elders and staff members who were concerned about the direction of the church.

Before the October 17 suit—which also names Mahoney’s wife and Bryant’s wife—the blog had not been updated all year. They declined to answer questions from CT, citing the legal proceedings, but wrote online in response:

While the authors of this website would never have chosen to resolve our differences in a litigious manner, we are confident that the legal process will ultimately uphold the values of the first amendment right to freedom of religion, freedom of speech and freedom of the press, all of which are essential to safeguarding the values of the Protestant Reformation and our common life.

Last week, a Cook County judge declined to hear the church’s request for an emergency restraining order, which would bar The Elephant’s Debt and Roys from publishing about MacDonald and Harvest while the case proceeded, but the filing has been continued for a hearing on a new date.

The defamation complaint from Harvest includes charges under the Illinois Deceptive Trade Practices Act of using false or misleading information to disparage the work of the church. The church claims that Roys, a former Moody Radio host and writer, works in partnership with The Elephant’s Debt, though her name does not appear in their postings prior to the discussion of the recent case.

The lawsuit references canceling Roys’s appearance as a keynote speaker at a Harvest women’s event “on or about February 2017,” due to her criticism of Moody Bible Institute. Her falling out with Moody came to a head at the start of this year, in January 2018, and the event had been scheduled for March of 2018.

Though MacDonald and Harvest allege Roys made public statements defaming the Harvest pastor, they do not appear on her social media channels, blog posts, or radio show history.

The suit also accuses her of privately telling former Moody chair Jerry Jenkins that MacDonald’s Walk the Word radio program “was only kept on Moody radio … because they were poker buddies.” (World Magazine reported in 2013 on Jenkins’s poker hobby and how he and MacDonald had played together in the past—one point of contention brought up on The Elephant’s Debt. The Harvest pastor announced the year prior that he gave up his Texas Hold ’Em habit due to public scrutiny.)

This September, Roys was working on a story for World magazine about the church and, according to Harvest, “asserting false allegations” during her investigation.

“The most telling thing in the entire suit is the fact that it states I am working on an investigative story about James MacDonald and Harvest Bible Chapel,” she wrote on Facebook. “I always knew I ran the risk of being sued for speaking the truth. But I always envisioned that it would be for something I actually published, not for something I merely indicated I was going to publish.”

World editor-in-chief Marvin Olasky confirmed to CT that Roys had been looking into Harvest for the magazine. “We are planning to run an article once we have thoroughly checked all facts and made sure everything is established by the testimony of two or more witnesses,” he said. “We would like to quote the responses of Harvest officials to serious concerns: Julie has unsuccessfully tried to interview current leaders on-the-record.”

Defamation suits are relatively rare among US congregations and don’t rank among the top reasons churches end up in court. But when they do come up, slander and libel claims involving Christians tend to go the other way: Ex-members will sometimes sue over critical remarks made during sermons, church discipline meetings, or other settings. Church Law & Tax has reviewed churches’ liability for such claims. Back in 2012, CT reported on a Calvary Chapel pastor who sued his son over an “online hate campaign.”

“You don’t see churches suing disgruntled former members often because they don’t have grounds,” attorney Charles Philbrick, who is representing Roys, told CT. “When people leave churches, really what they are voicing are their opinions, and opinions are not actionable per se.”

Additionally, Christians often cite biblical guidance on conflict resolution and work to avoid litigation if possible. MacDonald, who founded Harvest 30 years ago and decided to have the congregation join the Southern Baptist Convention in 2015, defended the decision to sue in an October 2 letter entitled “Enough is Enough”:

It isn’t that some of the criticism wasn’t fair. I believe in the marketplace of ideas and of regular, vibrant discussion inside a local church. It’s just that their words were often untrue, their information was incomplete, and over time their tone of reasonableness disintegrated, exposing their obvious goal of ending our ministry….

We sought reconciliation with former leaders or staff the bloggers identified as offended. Yet it was never enough.

The letter referenced his broader concerns over online accusations in the so-called fake news era, with bolded subtitles reading, “Bloggers Without Credibility are Given Too Much Credence,” “Attack Blogs Need a Perfect Storm,” and “More Ministries May Follow Suit.”

In 1999, CT Pastors created a 13-point guide for ministry leaders looking to respond biblically to accusations; the potential for spreading criticism against pastors and churches has only grown with the rise of social media and the Internet.

MacDonald also posted an excerpt from Wayne Grudem’s Christian Ethics that urges pastors to take action rather than “allow their own names or the ministries they lead to be slandered relentlessly in the public eye,” citing Jesus’ defenses against false accusations.

When asked about the timing of the lawsuit, a Harvest spokesperson told CT, “It is not our intention to try this case in the realm of public opinion, and, therefore, we have no plans at this time to make any additional public comment except for the explanation we published on our website, principally intended for our church members.”

In a section of Harvest’s website dedicated to “transparent communication about ongoing opposition,” the church links to letters sent at the beginning of October to both Roys and The Elephant’s Debt.

Steve Huston, elder executive committee chairman, emailed Roys to say the elders were concerned that her forthcoming story would challenge MacDonald’s integrity. “We have come to the end of our willingness to be lied about and are ready to take every reasonable measure to protect our church family,” he wrote. Roys replied that she would only meet with the elders if their discussion could be on the record.

Ron Duitsman, elder board chairman, wrote Mahoney and Bryant, asking that they take down their campaign to discredit MacDonald and Harvest since the church has “repented where appropriate.”

The bloggers called the lawsuit “stunning.” Their readers have donated almost $5,000 on Go Fund Me to cover initial legal fees.

Last year, The Elephant’s Debt scrutinized MacDonald’s shifting roles at Harvest Bible Chapel and its church planting ministry, Harvest Bible Fellowship.

In June 2017, MacDonald resigned as president of Harvest Bible Fellowship, which planted more than 150 congregations over about 15 years, and he and Harvest Bible Chapel cut official ties with fellowship churches, several of whom went on to rename their congregations. Instead of Harvest Bible Fellowship, an independent network called Vertical Church now builds on MacDonald’s church-planting philosophy to continue to train and support church planters.

Around the same time that his role with Harvest Bible Fellowship ended, Harvest Bible Chapel reorganized its leadership structure “to lighten the pressure on Pastor James” by having executive staff report to an executive committee rather than MacDonald directly. Elders wrote last October that the change would “relieve Pastor James of the burden of church management, allowing him to focus on the preaching, writing, and training he wants to prioritize.”

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that a judge dismissed Harvest’s request for a temporary restraining order; instead, the request has been continued for a hearing on a later date.