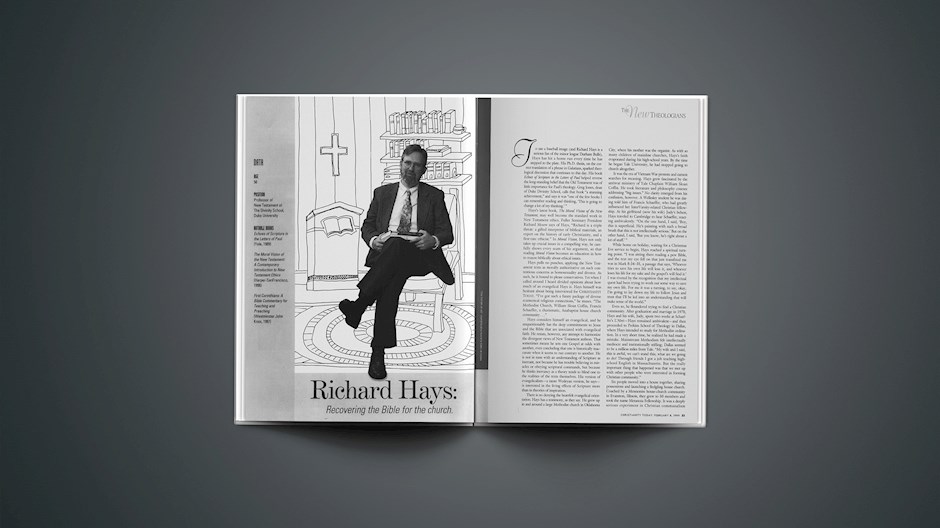

Richard Hays hardly seems like a daredevil. He is a quiet, bearded professor of New Testament at Duke Divinity School, the very picture of a measured personality. While still young and relatively unknown, Hays took on Yale University's John Boswell, famous for his scholarly vindication of homosexuality in Scripture. Hays politely demolished Boswell's pro-gay interpretation of Romans 1 as a textbook example of bad exegesis. The late Doctor Boswell huffily refused to respond, refused even to speak to Hays.

Hays was perhaps even more audacious in a paper he presented at the 1996 conference of the Society of Biblical Literature (SBL) in New Orleans, for it took on one of the darlings of modern academia, the "hermeneutic of suspicion." The hermeneutic of suspicion is the cornerstone of much modern scholarship in that it suggests that nothing can be taken at face value. It follows the "masters of suspicion"—Marx, Nietzsche, Freud, and more recent French postmodernists like Foucault—in seeking to unmask the strategy of power that allegedly lies behind every text. The Bible, for example, offers itself as a divine message of liberating love, but a suspicious reading might discover that the Bible's talk of a supernatural realm actually masks a desire to pacify or distract people so that they can be more easily oppressed.

In his paper, later published in the Christian Century, Hays admitted that suspicion is a useful tool. He wondered, however, why scholars had come to be endlessly suspicious of the text and not at all suspicious of themselves. Why were they so "remarkably credulous about the claims of [their own] experience"? He cited feminist critic Elisabeth Schssler Fiorenza, who seeks to use "women's own experience and vision of liberation" as a norm for assessing the Bible. What use, Hays asked, was a critique that never seemed to actually listen to the Bible and allow it to critique us?

His paper called for a "hermeneutic of trust" like that which Paul used as he read the Old Testament Scriptures. Taking his argument to its ultimate, provocative extreme, Hays asked scholars to approach Scripture as sinners—as those who "have filth in their souls." "We come to the texts of scripture expecting to find the hidden things of our hearts laid bare and expecting to encounter there the God who loves us." Hays was asking for nothing less than a reverent, humble, Christian reading of the Bible—a stance that is rarely, if ever, articulated in American universities.

Though hundreds of papers are read at the SBL meetings, usually to an emotionally distant audience of professionals, this occasion was decidedly different. "The response was stunning to me," Hays remembers, "a standing ovation from a crowd of two or three hundred people. I don't think it was because it was such a brilliant paper. I think it was that I had articulated a deep longing of a lot of people in the guild to recover the capacity to hear the word of God in the text."

In one sense, Hays and others like him are "new" theologians because they are replacing an older generation of theologians and Bible scholars in top university and divinity school posts. But "new" also fits them because of their fresh approach to old issues and because they refuse to work within the paradigms inherited from their academic progenitors.

These scholars may represent the dawn of a new era in religious scholarship—though the issue won't be settled until a few decades from now. But it is already apparent that "the new theologians" profiled in this special section—Richard Hays, Miroslav Volf, Kevin Vanhoozer, N. T. Wright, and Ellen Charry—signal a discernible and surprising shift within the fields of biblical studies and theology. They certainly do not represent the majority of their peers. Yet their work—articulating an unapologetically orthodox faith—is highly regarded in the academy.

Until recently, evangelical scholars were rarely comfortable in the university, and the few in it usually assumed a prophetic stance—analyzing what had gone wrong in scholarship and defending evangelical orthodoxy. Standing outside the mainstream, they rarely received much attention beyond their own circles.

Recently, though, a handful of orthodox Protestant scholars has gained a wider voice, speaking with a different tone and articulating a different vision. Especially in the fields of philosophy and American church history, outspoken believers like Nicholas Wolterstorff, Alvin Plantinga, Mark Noll, George Marsden, and Timothy Smith, to name a few, have achieved sterling reputations. In this section, however, I have chosen to focus on believing scholars doing their work in theology and Bible, because these studies are closest to the evangelical heart and are thus charged with more difficulties.

In meeting with each of the five scholars and their peers, I quickly discovered that the word evangelical makes academics nervous. The term can be confused with both the Religious Right and with fundamentalism, to which the world of scholars has a serious allergy. But they all agreed that the intellectual world is no longer dominated by a liberal-conservative polarity, with liberalism holding all the intellectual forts and conservatives shooting arrows from the outside. These scholars don't experience a rigid, anti-evangelical consensus. Rather, they see open space. The demise of modernism has knocked down most of the forts.

What does the future hold for theology? Not one person I talked with claimed to have any sure answer to that. Current methodologies and perspectives are radically diverse, and there are challenges and problems on all sides. No voices dominate the conversation.

But if it is true that the end of modernism has left a wide-open space and that the old polarities no longer dominate the field, new voices can be heard.

I heard some of those new voices. They seem quite at home in a pluralistic world, confident without being cocky, distinctive without being defensive. They don't aim to attack an orthodox liberalism—for they say there is no longer such a thing. They aim, rather, to witness—to witness publicly, in the church and in the world and even in academia, to Jesus Christ. These thinkers bear watching.

Richard Hays Professor of New Testament

The Divinity School,Duke University

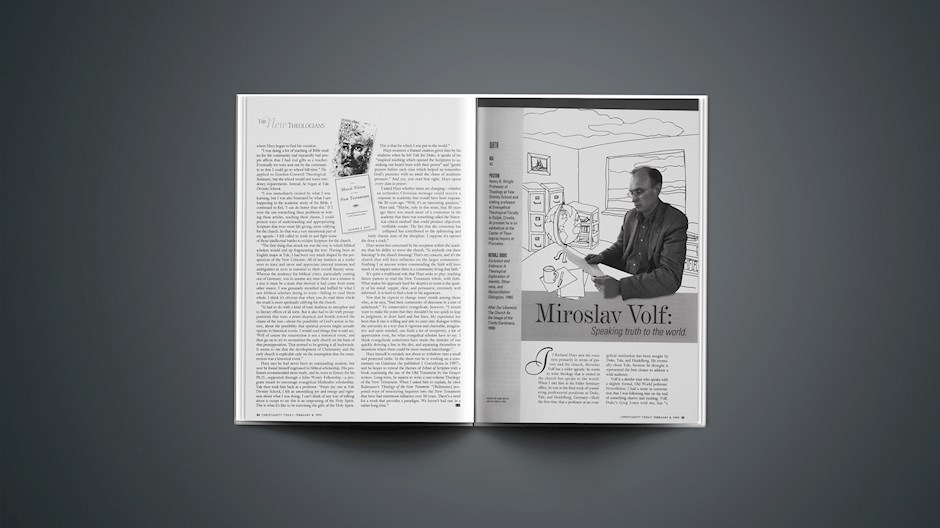

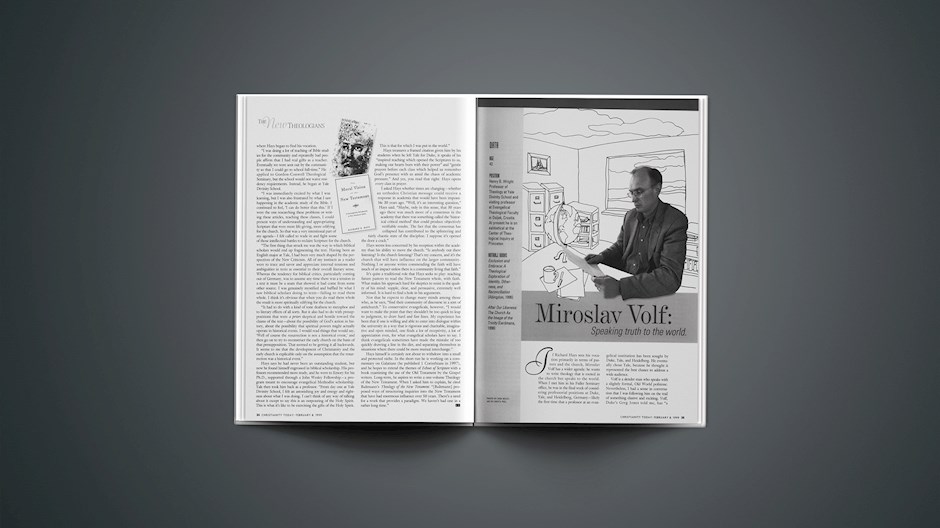

Miroslav Volf Henry B. Wright Professor of Theology

Yale Divinity School

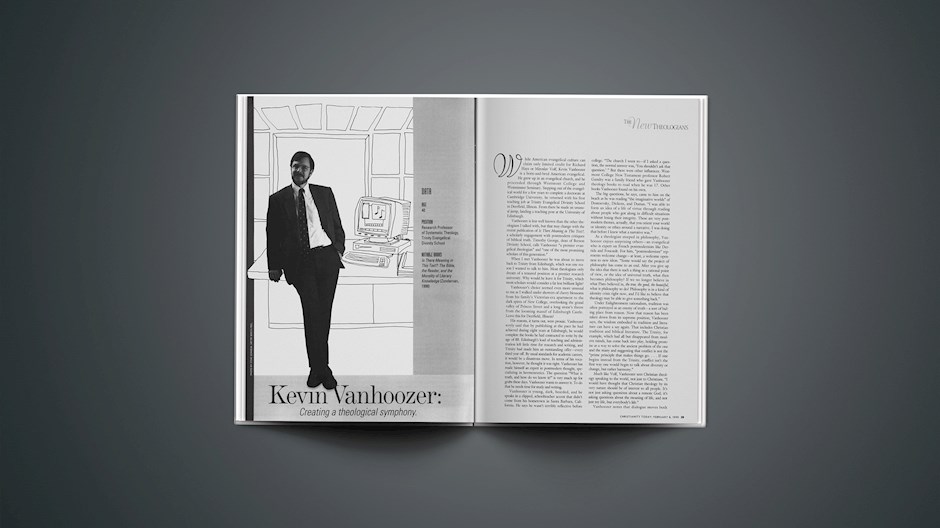

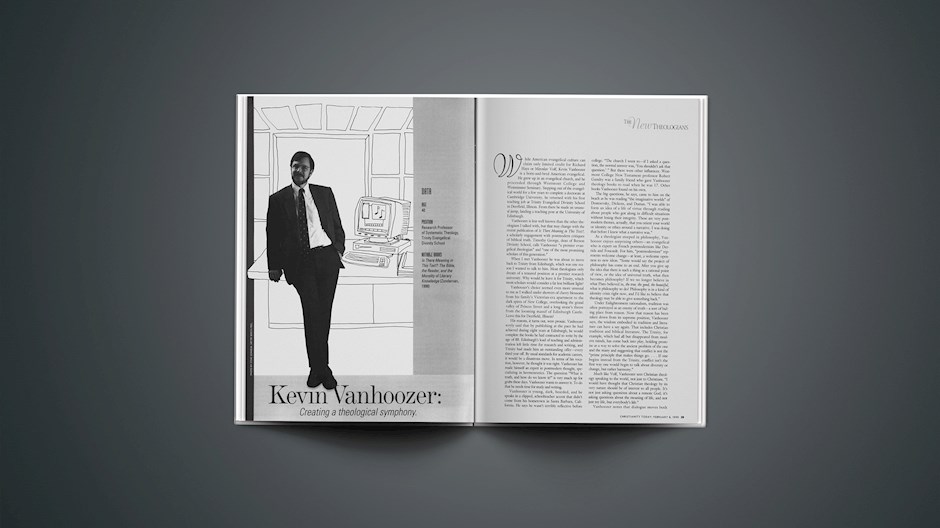

Kevin Vanhoozer Research Professor of Systematic Theology

Trinity Evangelical Divinity School

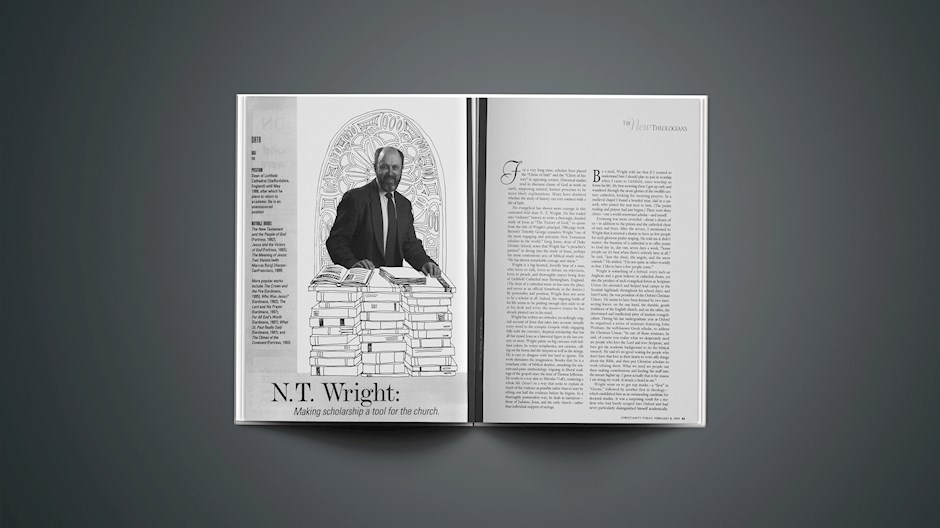

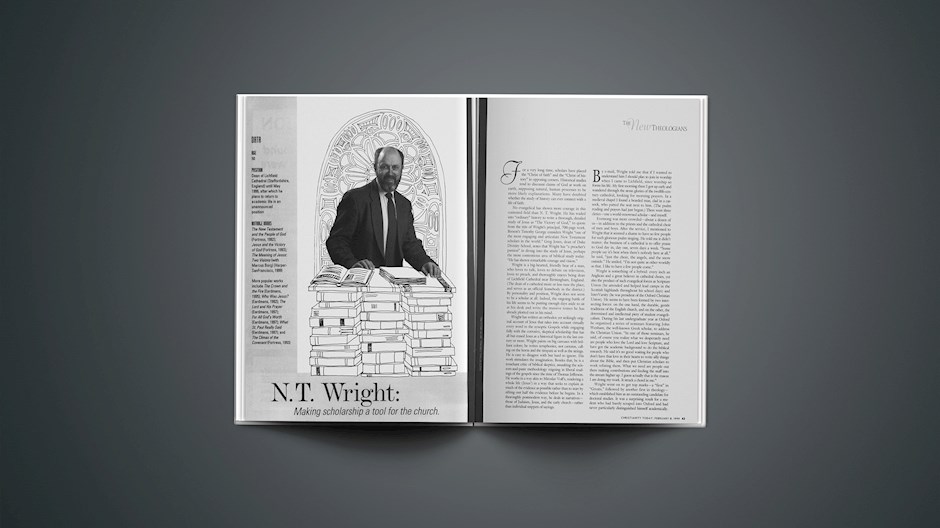

N. T. Wright Dean

Lichfield Cathedral Staffordshire, England

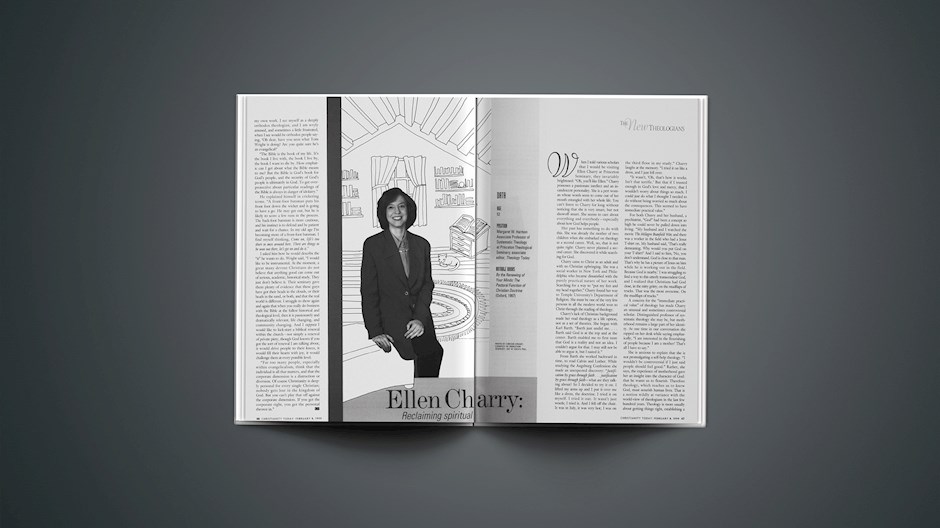

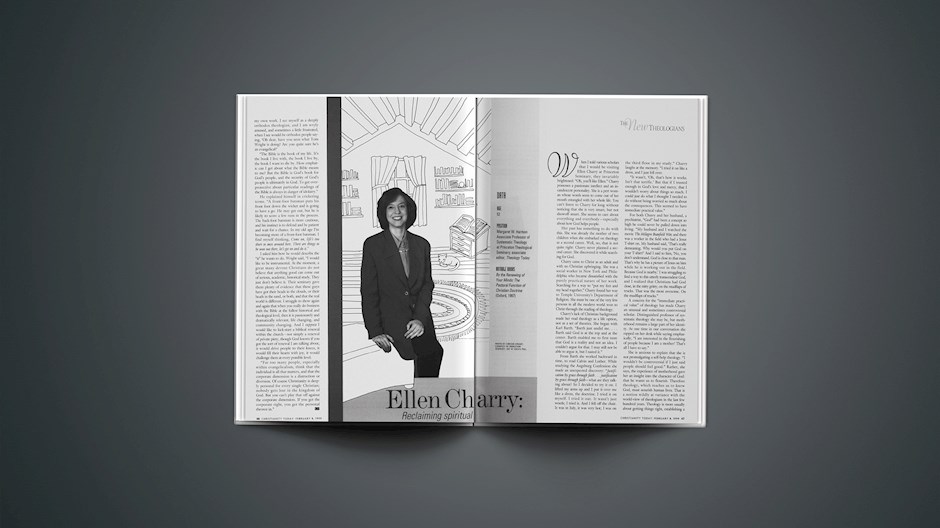

Ellen Charry Margaret W. Harmon Associate Professor of Systematic Theology

Princeton Theological Seminary

Copyright © 1999 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.