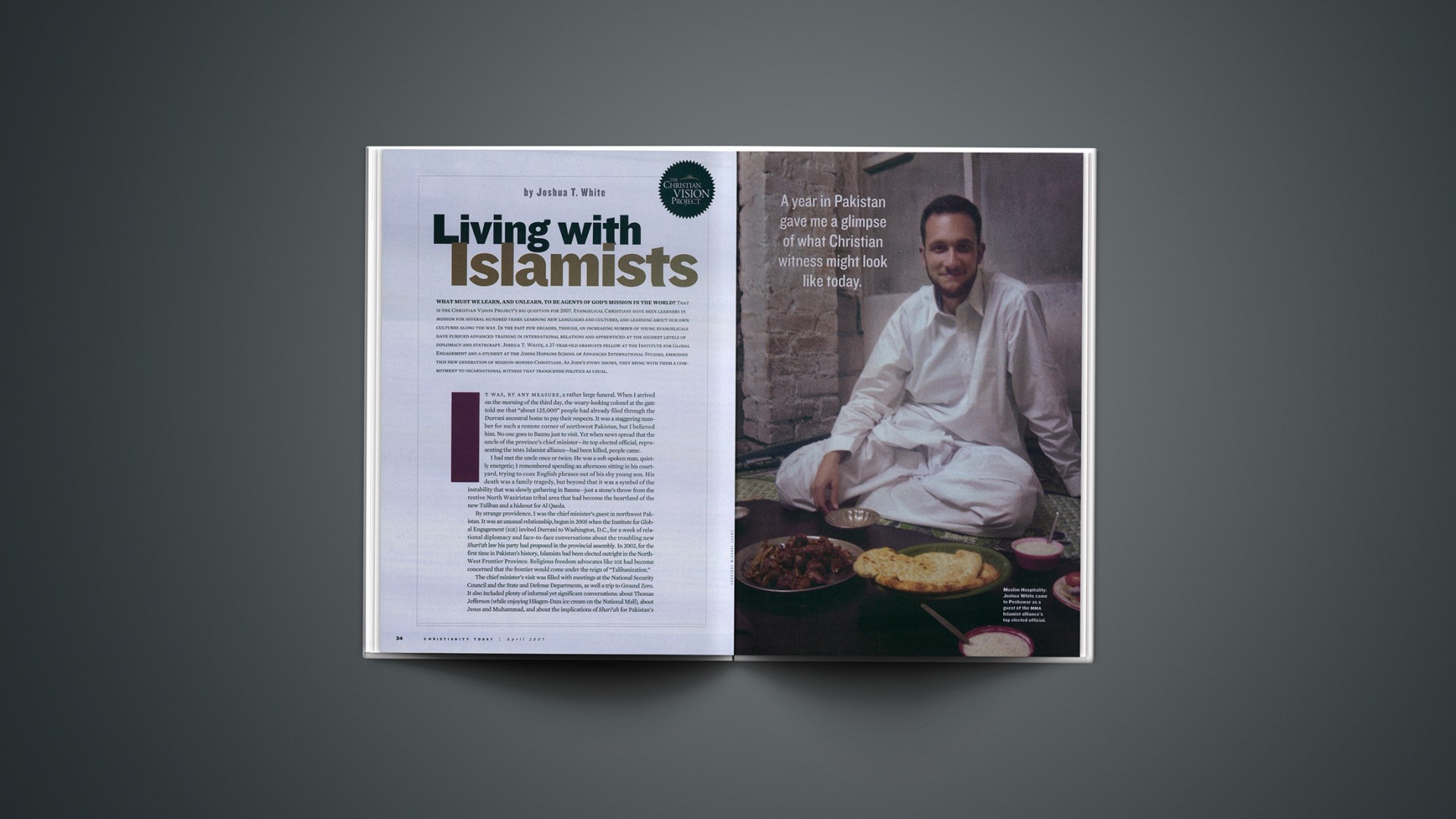

What must we learn, and unlearn, to be agents of God’s mission in the world? That is the Christian Vision Project’s big question for 2007. Evangelical Christians have been learners in mission for several hundred years: learning new languages and cultures, and learning about our own cultures along the way. In the past few decades, though, an increasing number of young evangelicals have pursued advanced training in international relations and apprenticed at the highest levels of diplomacy and statecraft. Joshua T. White, a 27-year-old graduate fellow at the Institute for Global Engagement and a student at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, embodies this new generation of mission-minded Christians. As Josh’s story shows, they bring with them a commitment to incarnational witness that transcends politics as usual.

It was, by any measure, a rather large funeral. When I arrived on the morning of the third day, the weary-looking colonel at the gate told me that “about 125,000” people had already filed through the Durrani ancestral home to pay their respects. It was a staggering number for such a remote corner of northwest Pakistan, but I believed him. No one goes to Bannu just to visit. Yet when news spread that the uncle of the province’s chief minister—its top elected official, representing the mma Islamist alliance—had been killed, people came.

I had met the uncle once or twice. He was a soft-spoken man, quietly energetic; I remembered spending an afternoon sitting in his courtyard, trying to coax English phrases out of his shy young son. His death was a family tragedy, but beyond that it was a symbol of the instability that was slowly gathering in Bannu—just a stone’s throw from the restive North Waziristan tribal area that had become the heartland of the new Taliban and a hideout for Al Qaeda.

By strange providence, I was the chief minister’s guest in northwest Pakistan. It was an unusual relationship, begun in 2005 when the Institute for Global Engagement (IGE) invited Durrani to Washington, D.C., for a week of relational diplomacy and face-to-face conversations about the troubling new Shari’ah law his party had proposed in the provincial assembly. In 2002, for the first time in Pakistan’s history, Islamists had been elected outright in the North-West Frontier Province. Religious freedom advocates like IGE had become concerned that the frontier would come under the reign of “Talibanization.”

The chief minister’s visit was filled with meetings at the National Security Council and the State and Defense Departments, as well a trip to Ground Zero. It also included plenty of informal yet significant conversations: about Thomas Jefferson (while enjoying Häagen-Dazs ice cream on the National Mall), about Jesus and Muhammad, and about the implications of Shari’ah for Pakistan’s fragile minority communities. In spite of our political and religious differences, we found the chief minister to be something of a moderate in his context. Before departing, Durrani invited us to see the frontier for ourselves.

A few months later we did, amid the terrible October earthquake. While there, the chief minister signed an agreement with IGE to work together on religious freedom through interfaith and education projects. I was so taken with the history and hospitality of the frontier that I decided to stay for a year in the provincial capital of Peshawar, pursuing these programs.

That a 27-year-old American Christian was hanging out in Peshawar as the guest of an Islamist political party that four years earlier had come to power on a pro-Shari’ah and anti-American platform caused no end of wonder to the local diplomats and church community. To them, it seemed a bit crazy. For me, it was an extraordinary opportunity to glimpse Islamist political leadership from the inside; to get to know these people as people; to begin to tease apart rhetoric from reality, slogans from conviction; and to find myself, on a certain scorching May morning, the only Westerner making a trip down to Bannu.

The Art of Doing Prayer

The road south from Peshawar is picturesque in a dusty sort of way. It meanders through a barren landscape of scattered villages, tribal areas beyond the legal authority of the government, abandoned checkpoints, and roadside stands crowded with old men slurping goat milk chai off of delicately balanced British-era tea saucers.

Arriving in Bannu, I was ushered into the family hujrah, a large walled courtyard. The family had erected an enormous white tent, overflowing with visitors: family friends, prominent politicians, and a small sea of old bearded tribal elders from Waziristan, sitting with their canes in one hand and their cups of chai in the other. Aside from the tent, it could have been a scene from a tribal gathering 500 years ago.

The chief minister sat at the center. When he saw me, he stood and smiled—amused, I think, at my scruffy beard, my white tunic, and my already-frayed Peshawari sandals. I greeted him as best I could, earnestly, with a hand over my heart and a phrase suggested by my Urdu teacher: Main ap ke gham men barabar ka sharik hun. “I am an equal partner in your sorrow.” I added, simply, “We’re doing prayer for your family.”

Muslims in Pakistan speak of two forms of prayer. The obligatory prayer practiced five times a day is namaz, and since this prayer is often read in the mosque, the verb is to read namaz. (There is a physical shorthand, too: cupping one’s hands behind the ears, the first gesture of obligatory prayer.) The other form of prayer is du’a, which is more situational, more freeform. To do du’a is to offer a prayer on someone’s behalf, and when saying du’a the hands are raised, palms back, to about eye level and held there while the prayer is spoken, or while a moment of silence passes.

When honoring the dead, a silent du’a is said. And it is said communally, such that when I sat down next to the chief minister, raised my hands, and softly said du’a kare, “let us do prayer,” the whole tent in an instant responded by raising their hands with me in a wave of joint supplication—the politicians, the family, the elders with their canes—and praying in absolute silence for the soul of the departed. The moment of silence lingered, all eyes on us, until, in the traditional style, I passed my hands over my face and closed with a quiet Ameen.

In so many ways, my worldview differed from that of the people in the tent. Yet a communal prayer for a lost family member is a profoundly human moment. The image of that moment has stuck with me, because it is a picture of two things I found to be true of northwest Pakistan.

First, the vast majority of people I met were gracious to a fault, hospitable, and quick to condemn violence in the name of religion. They were, at the same time, largely uninterested in trying to delineate the boundaries of religion in public life. “Islam,” I was often told, “is about all of life.” Coming from an American culture in which religion is often considered unwelcome in the public square, this was a real change. For better and for worse, religion in Pakistan is more than the language of private devotion; it is still the most potent language of public life as well.

Second, in spite of feeling far from home, time and time again I found that I felt surprisingly comfortable in Pakistan, precisely because it was a deeply religious society. Despite the points of shared history and shared values, at the end of the day, I believe something quite different than the Muslims I met and lived with and prayed among. But I still came away admiring their devotion and appreciating a society in which religious conversation and values are honored.

Easter as a Security Event

Christians in Pakistan are the poorest of the poor. Largely the remnant of low-caste converts who followed British garrisons northward during the days of the Raj, they are predominantly sweepers and toilet cleaners. Of the 20 million people in the North-West Frontier Province, they number only 100,000. While their experience under the Islamist government has been better than many feared, they have nonetheless learned to live with the constant anxiety of being a minority. Last year, I witnessed firsthand the Danish cartoon-instigated rioting in Peshawar, in which a Catholic school was vandalized. (Ironically, the greatest damage was done to the local KFC: A mob of schoolchildren burned it down, but not before stealing the fried chicken.)

Religious minorities in Pakistan must learn to live with their expressions of faith being put under a microscope, struggling to find the proper balance between public conviction and sensitivity to the majority culture. One of my most memorable experiences in Peshawar reflected this deep and unending tension.

I was invited by a young friend to participate in the annual Easter march in Peshawar’s Old City, a tradition dating back at least 40 years. I can’t imagine there are many places in the Muslim world where this happens.

At three o’clock in the morning, my friend drove me to the heart of the Old City. There we joined what was an extraordinary scene—hundreds of Christians marching through dark, narrow streets, with candles lit, in a line that stretched for an entire block. At the front of the line were Anglicans and Catholics, marching in their vestments. After them came—what else?—a decorated Suzuki minibus, with a pa system mounted on top and an eager young preacher in the passenger seat belting out sermons in Urdu, then Pashto, then Punjabi. Behind the minibus came a tightly packed crowd of dancing Pentecostals, who, much to the relief of the nervous Anglicans, somehow managed to keep moving along with the crowd. And all around this scene—around the flickering lights and the children singing hymns and the minibus creeping through the dark streets in the wee hours of Easter morning—were policemen.

It was my first Easter celebrated within a police cordon.

What dissonance to be saying “Jesus is risen!” in the still-dark streets of an ancient Muslim city while surrounded by men with batons and Kalashnikovs. Part of me felt a measure of awe that a state—an Islamic republic, no less—would go to such lengths to protect a declaration that has no standing in its received revelation. Another part of me felt a despairing sadness that police were necessary and that Easter needed to be managed as a security event. Amid all this, in spite of the dissonance of it all, I kept coming back to a lingering sense that this experience must be truer to that of the early Christians than the grand, note-perfect pageants I had come to know as “Easter Sunday.”

I celebrated Easter in Peshawar as an outsider, as someone who had internalized only a small part of what it is to be a minority—the fundamental insecurity of being few among many. But for me, at least, even that fractional experience was enough to breathe new meaning into the words of the liturgy: Dying, he destroyed our death. Rising, he restored our life. Lord Jesus, come in glory.

In light of my experience with the suffering church in Pakistan, I feel more deeply the truth that has been reiterated many times in these pages: that the church in the West needs to redefine success and “suffer with those who suffer”—with Christian brothers and sisters, but also with the whole range of religious communities worldwide who feel overshadowed, beleaguered, and forgotten.

We also need to find ways to broaden the way we practice Christian witness in this post-9/11 world. When IGE invited Durrani to Washington, we came under criticism for hosting “bloodthirsty bigots.” The criticism stung, but as my experience in Pakistan unfolded, what stung even more was finding that I had been sold a bleak picture of the Muslim world so at odds with my experience of the Pakistani people. What also stung was encountering hundreds of Pakistanis who had never before honestly interacted with someone from my country or of my faith.

Never once in Pakistan did I bring up the subject of religion, yet somehow I was always talking about it. People flooded me with questions: What do you think of the clash of civilizations? What do Christians believe about the prophet Jesus? Do Americans hate Islam? And my favorite, posed by a rather baffled old mullah: What is premillenial dispensationalism? My Muslim Pakistani friends were gracious enough to interpret for me their world and their faith. In light of our incarnational imperative, we Christians ought to be more eager to do the same.

I have come to think that this kind of interpretive witness is one calling of a true global citizen, and certainly of a Christian who takes seriously the way of Jesus. It is a witness that doesn’t ignore the realities of politics and the brutalities of modern terrorism, but responds with something more than power and pragmatism. It is a witness that looks for ways to engage those who have divergent visions of faith and society and advocates for fundamental religious freedoms. More than anything, it is a witness that stitches together humility and conviction in the messiness of the real world—and does so in a way that points quietly, but inevitably, to the faith we profess.

Copyright © 2007 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Joshua White‘s biography is available at the Institute for Global Engagement.

IGE also has a profile, slideshow, a trip report, an article on the 2005 earthquake, and other resources on Pakistan.

Recent Christianity Today articles on Pakistan and Islam include:

Love Your Muslim as Yourself | We remain woefully ignorant about the world’s second-largest religion. A Christianity Today editorial (March 16, 2007)

Can we dialogue with Islam? | What 38 Muslim scholars said to the pope in a little-known open letter. (January 1, 2007)

Life, Liberty, and Terrorism | How much freedom should we give up in national emergencies? (John Wilson, March 21, 2007)

The Problem with Hating Religion | A scholar rescues the reputation of generation of Middle East scholars. (John Wilson, January 22, 2007)

Earlier Christian Vision Project articles on mission include:

On a Justice Mission | Thanks to William Wilberforce, we already know the key to defeating slavery. By Gary Haugen (Feb. 22, 2007)

A Community of the Broken | A young organization models what it might mean to be the church in a suffering world. By Christopher L. Heuertz (Feb. 9, 2007)

An Upside-Down World | Distinguishing between home and mission field no longer makes sense. By Christopher J. H. Wright (Jan. 28, 2007)

Christian Vision Project articles on culture include:

The Importance of Knowing What’s Important | Being a counterculture for the common good begins with what we choose to focus on–and to overlook. By Andy Crouch (December 14, 2006)

Behold, the Global Church | It’s time we figured out how to talk–and listen–to one another. By Brenda Salter McNeil (November 17, 2006)

The Church’s Great Malfunctions | We should be our own fiercest critics, doing so out of the deep beauty and goodness of our faith. By Miroslav Volf (November 10, 2006)

For Shame? | Why Christians should welcome, rather than stigmatize, unwed mothers and their children. By Amy Laura Hall (September ,1 2006)

Our Transnational Anthem | ‘O say can you see … ‘ a church where many cultures work together in Christ? By Orlando Crespo (August, 2006)

Experiencing Life at the Margins | An African bishop tells North American Christians the most helpful gospel-thing they can do. Interview by Andy Crouch (July 1, 2006)

The Phone Book Test | Robert P. George explains how a simple experiment reveals the great divide in our culture. Interview by Andy Crouch (June 1, 2006)

A New Kind of Urban Christian | As the city goes, so goes the culture. By Tim Keller (May 1, 2006)

The Conservative Humanist | Those who are pro-life and pro-family should have no problem being pro-human. By Glen T. Stanton (April 21, 2006)

Loving the Storm-Drenched | We can no more change the culture than we can the weather. Fortunately, we’ve got more important things to do. By Frederica Mathewes-Green (March 3, 2006)

Habits of Highly Effective Justice Workers | Should we protest the system or invest in a life? Yes. By Rodolpho Carrasco (Feb. 3, 2006)

How the Kingdom Comes | The church becomes countercultural by sinking its roots ever deeper into God’s heavenly gifts. By Michael S. Horton (Jan. 13, 2006)

Inside CT: Better Than a Cigar | Introducing the Christian Vision Project. By David Neff (Jan. 13, 2006)