This article was originally published in 2002.

On September 23, thousands of people filed into New York City's Yankee Stadium, waving American flags and clutching photos of missing loved ones presumed dead 12 days after the terrorist attacks. The hope had faded for finding survivors at Ground Zero, the 2 million-ton pile of debris in lower Manhattan, and the victims' families and friends gathered together at this interfaith prayer service to mourn.

The program featured a hastily assembled jumble of Christian, Muslim, Jewish, Sikh, and Hindu clergy and musical performers like Bette Midler and the Harlem Boys & Girls Choir. The service was profoundly religious yet utterly pluralistic, and in Mayor Rudy Giuliani's mind there was really only one national personality who could serve as its host: her low, distinctive voice both comforted and inspired the bereaved.

"When you lose a loved one, you gain an angel whose name you know," said Oprah Winfrey. "Over 6,000, and counting, angels added to the spiritual roster these past two weeks. It is my prayer that they will keep us in their sight with a direct line to our hearts." After reminding mourners that "hope lives, prayer lives, love lives," she offered an affirmation tinged with challenge and benediction: "May we all leave this place and not let one single life have passed in vain. May we leave this place determined to now use every moment that we yet live to turn up the volume in our own lives, to create deeper meaning, to know what really matters."

Fast forward to Chicago a few weeks later. About 300 people are seated around a small wooden platform at Harpo Studios for a taping of The Oprah Show. The audience is mostly women, generally well coifed and well dressed. Gina, a chatty producer, takes the stage and explains that today they will tape two episodes of the "Dr. Phil Get Real Challenge," in which 42 participants spend five days having their emotional hides tanned by Dr. Phil McGraw, the tough-talking psychologist and "life strategist" who has become a regular on the show.

Then it happens. The theme music rolls, the audience erupts, and she appears, gliding in on the arm of Dr. Phil, radiant in a yellow pantsuit, gorgeous hair, that hey-girl-how-you-doin' smile, that voice. In that moment, people in the audience are united in excitement; they become her shameless groupies. They will read whatever books she endorses, ponder her every word, keep gratitude journals, donate money, remember their spirits, whatever. This isn't Jerry, Ricki, or Rosie. This is Oprah!

After the show, as is her custom, Oprah entertains questions from curious audience members. What, one woman asks, is one of the most important experiences she's ever had? A common question, but Oprah obliges her and refers to the infamous 1998 trial in which a group of Texas cattlemen sued her after she expressed reluctance to eat burgers ever again during a show on mad cow disease. The cattlemen's lawyer had accused her of intentionally causing beef stock prices to fall.

She won the trial, Oprah told the audience, when she began to see it as a metaphor for life's trials. "I kept asking God, 'What is the deeper meaning of this? It can't be about burgers,'" she said. Then she received the revelation: "I became calm inside myself and I thought, The outside world is always going to be telling you one thing, have one impression—accusatory, blaming, and so forth. And you are to stand still inside yourself and know the truth, and let it set you free. And in that moment, I won that trial."

As the story reaches its climax, a small, elderly black woman in a turquoise Sunday suit rises from her seat and claps her hands. "Yes!" she shouts with the joy of one who likes a good testimony. The audience claps approvingly.

These two incidents—the New York memorial service and Oprah's informal testimony time with her studio audience—illustrate the blurring of the popular and pastoral, the self-help and the sacred, in the woman who is Oprah.

In the 16 years since The Oprah Show began syndication, Oprah Winfrey has evolved from a chatty talk show host with down-home sensibility into a "one-woman brand name" whose business acumen has allowed her to become one of the richest and most influential people in the world. Since 1986 her show, which is now seen in 112 countries, has been a perennial champion in the daytime ratings. Juggling it, her book club, her Web site, her Angel Network benevolence fund, her series of television movies, O: The Oprah Magazine, and the Oxygen cable channel, Oprah is clearly one of the most influential media figures in the world.

But her effect extends beyond media. She is a force that has permeated the way we think about culture and interpersonal communication. The Wall Street Journal coined the word Oprahfication to describe "public confession as a form of therapy." Jet magazine uses Oprah as a verb: "I didn't want to tell her, but. … she Oprah'd it out of me." Politicians now hold "Oprah-style" town meetings to gauge the mood of their constituents.

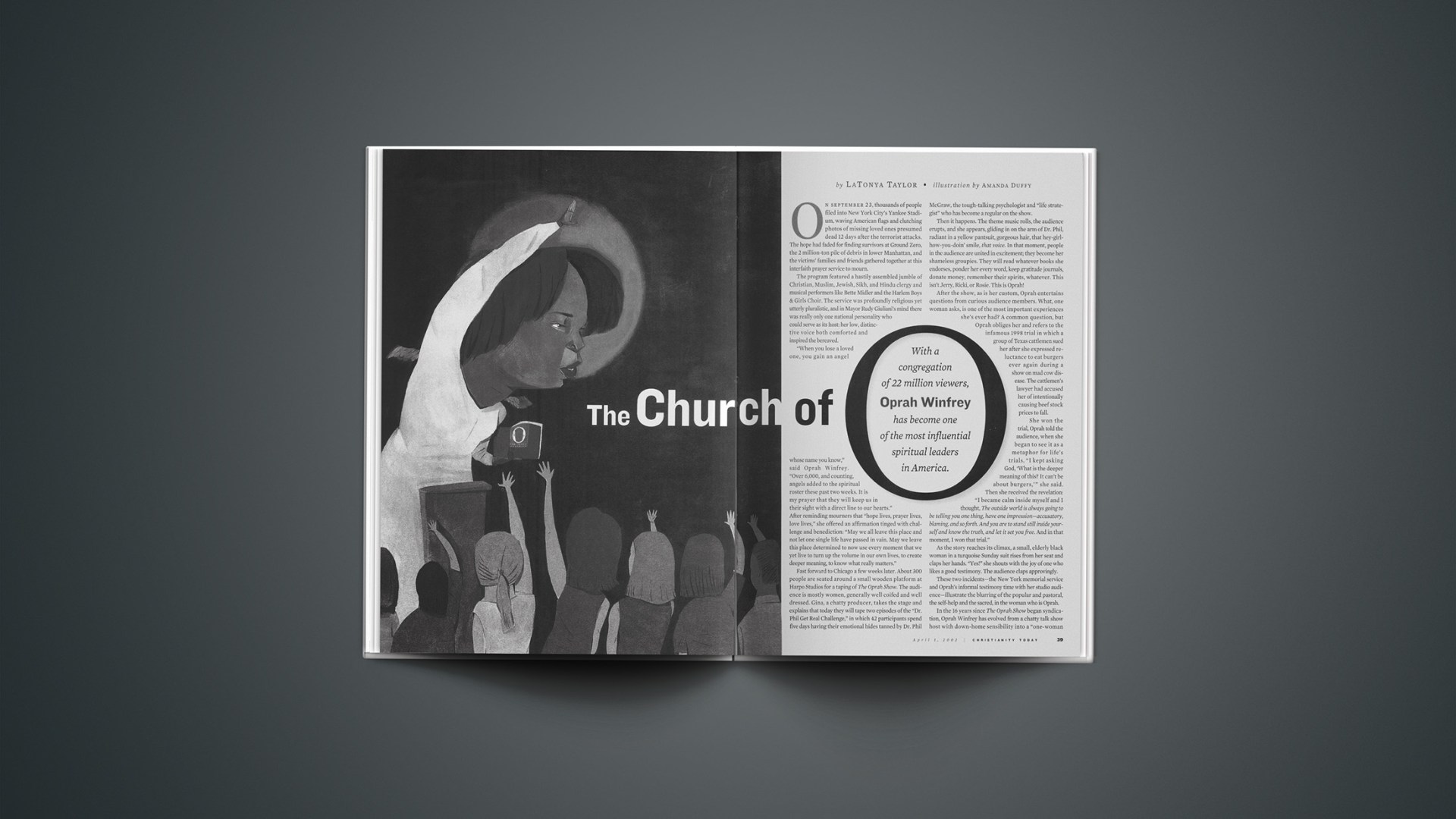

Since 1994, when she abandoned traditional talk-show fare for more edifying content, and 1998, when she began "Change Your Life TV," Oprah's most significant role has become that of spiritual leader. To her audience of more than 22 million mostly female viewers, she has become a postmodern priestess—an icon of church-free spirituality.

"Oprah Winfrey arguably has more influence on the culture than any university president, politician, or religious leader, except perhaps the Pope," noted a 1994 Vanity Fair article. Indeed, much like a healthy church, Oprah creates community, provides information, and encourages people to evaluate and improve their lives.

Oprah's brand of spirituality cannot simply be dismissed as superficial civil religion or so much New Age psychobabble, either. It goes much deeper. The story of her personal journey to worldwide prominence could be viewed as a window into American spirituality at the beginning of the 21st century—and into the challenges it poses for the church.

Baptist Deacon's Daughter

Vernon Winfrey remembers parts of this story. He first met his daughter —the child of a brief affair he had at 21 while on Army leave—when she was 8 years old. Oprah Gail Winfrey was born January 29, 1954, in Kosciusko, Mississippi, where she lived on a tiny farm with her mother, Vernita, and grandmother, Hattie Mae Lee. Vernita found work cleaning homes in Milwaukee and sent for the little girl when she was 6 but found that she did not have room or money to care for Oprah and her younger half-sister. So Vernon drove up from his home in Nashville to pick up his daughter.

By then, her life had already been deeply influenced by the church. In fact, her unique name is actually a misspelling of Orpah, the daughter-in-law of Naomi, mentioned in Ruth 1:14. Hattie Mae taught Oprah to read the Bible, and because she had few playmates, Oprah says, she spent most of her time reading Bible stories to the barnyard animals.

Her grandmother taught her several lessons about God and faith, but one in particular stands out in her mind: "I remember when I was 4 watching my grandma boil clothes in a huge iron pot," Oprah has said. "I was crying, and Grandma asked, 'What's the matter with you, girl?' 'Big Mammy,' I sobbed, 'I'm going to die someday.' 'Honey,' she said, 'God don't mess with his children. You gotta do a lot of work in your life and not be afraid. The strong have got to take care of the others.' I soon came to realize that my grandmother was loosely translating from the epistle of Romans in the New Testament—'We that are strong ought to bear the infirmities of the weak' (15:1). Despite my age, I somehow grasped the concept. I knew I was going to help people, that I had a higher calling, so to speak."

Oprah had already begun to speak in church, loving the attention, the applause, and the feel of her little patent leather shoes. She would give brief recitations as early as age 3. Today, she calls it the "beginning of my broadcasting career. [I] loved being in front of people, dressed up, and being able to say my piece."

Vernon Winfrey continues to work at his small barbershop in Nashville, despite his daughter's fame and fortune. There, the slender 69-year-old with well-trimmed salt-and-pepper goatee and oval glasses pauses over a client, electric razor in hand, to demonstrate how Oprah would stand while giving a speech at Progressive Missionary Baptist Church. He draws himself to full height, throws back his shoulders and lifts his chin slightly, and for a moment, his Southern charm is replaced with something regal.

Every Sunday Mr. Winfrey would cover the seats of his 1950 Mercury, so lint wouldn't get on their Sunday clothes, and he and Oprah would drive to Progressive Baptist, where he was a deacon. Winfrey and his wife, Zelma, had noticed Oprah's interest in reading and purchased a set of Bible-story books for her. As a result, he says, she was often ahead of her Sunday school classmates.

Even as a little girl, she was attentive on Sunday mornings. "I never saw her sleep in church," Mr. Winfrey told CT. In fact, the next day on the playground at Wharton Elementary School, Oprah would often repeat the Sunday sermon, using notes she had taken at church. She called it the "Monday morning devotion."

She had learned the Golden Rule, written it over and over, and carried it around in her book bag. She wanted to be a missionary and, in an action that foreshadowed her more recent philanthropy, she donated her lunch money to Progressive's fund for poor Costa Rican children—and convinced her friends to do the same.

More than once, Oprah's knowledge of the Bible and speaking ability got her out of trouble. When several students told her they would beat her up after school, she talked her way out of a fight and into a new nickname—Preacher Woman.

If her gifts made her unpopular with other children, they made her the darling of the adults at Progressive. "A lot of the older folks got so much joy within [when she spoke]," Vernon Winfrey recalls. After Oprah recited William Ernest Henley's "Invictus" during one service, he says, "One of the older men came up to me and said, 'Brother Winfrey! Brother Winfrey! She's going places!' "

During that time, Oprah joined the church. "She just did it on her own," her father says. "She knew what she was doing."

Becoming 'Oprah'

After spending a year with her father, Oprah went back to live with her mother in Milwaukee. By the time she returned to her father's home as a 14-year-old, she had been sexually abused by male relatives and was a promiscuous teenager who was too much for her mother to handle. Vernita Lee tried to check Oprah into a home for troubled teens. Because the home was full, she called Vernon Winfrey in Nashville again. A few months after arriving in Nashville, Oprah gave birth to a baby boy, who died shortly thereafter.

Oprah has referred to her father's renewed involvement in her life as "my saving grace." Once again, she thrived in the structured life provided by Vernon and Zelma Winfrey and Progressive Missionary Baptist Church.

Most of the older members of 68-year-old Progressive best remember the teenage Oprah for organizing and directing a series of presentations from James Weldon Johnson's God's Trombones at local churches to raise funds for new robes for the church's youth choir. Oprah and other teens from the junior church would present the seven sermons in the book. Oprah usually did "The Crucifixion" and "The Prodigal Son."

She spoke frequently at Nashville churches. "She could just about hold you spellbound," says Deacon Carl Adams, a founding member of Progressive. "She would always give something that was fulfilling spiritually."

When a Los Angeles pastor heard her speak in Nashville, he invited her to his church and paid her $500 to speak to the youth, Mr. Winfrey recalls. While she was there, a trip to the Hollywood Walk of Fame reinforced her desire to become a star.

Oprah landed her first broadcasting job, reading the news at a local radio station, when she was 19. She left Tennessee State University to win a spot as a TV newscaster at a local CBS affiliate. (She completed her degree in 1986 and gave the commencement address in 1987.) From there, her prodigious talent and hard work would take her to greater opportunities. In 1977, she took an anchor job at a station in Baltimore. Then, in 1984, she moved to WLS-TV in Chicago to host a local talk show, which became such a hit that it eventually went national. The rest is pop-culture history.

From the beginning, Oprah regularly featured spiritual themes on her shows. But her emergence as a spiritual force in her own right began with the 1994-95 season. Oprah has said that each year she asks God for a different gift or insight. In 1994, she says, it was clarity. "I have become more clear about my purpose in television and this show," she told a reporter that year. She decided to clean up her program.

This conversion coincided with a backlash against the tabloid fare on talk shows like Oprah's. Vicki Abt, then a professor of sociology and American studies at Penn State, had criticized the show in a 1994 article in the Journal of Popular Culture. She had also written a book, The Shameless World of Phil, Sally, and Oprah: Television Talk Shows and the Deconstruction of Society. Abt says Oprah asked her to appear on the show to defend her claim that the Oprah show was "trash." They taped six hours together, which were edited down to two one-hour shows that aired in September 1994.

As a result, Abt has a more cynical reading of the change in the show. "I don't know if she found God; I think she found me," Abt says. She mentioned several ideas, she says, that were implemented without anyone crediting her.

"I said, 'Instead of showing people who have made disastrous life decisions and are cognitively challenged, why don't you show people who have been successful? Why don't you try to raise people by talking about foreign affairs, macro-issues, but also literacy?'" Abt told CT. "I said, 'Why don't you start a book club? Have an author on, tell everybody in advance who the author is going to be, and then they'll read the book.' Boy, do they read the book." Abt has since written another book, Coming After Oprah: Cultural Fallout in the Age of the TV Talk Show.

Whatever the reason for her shift in direction, Oprah has never looked back. She has successfully separated herself from the Jerry Springers of the world, not only through rejecting the My-Husband-Ain't-My-Baby's-Daddy content but also by methodically directing her audience to take an inward focus. For example, Oprah introduced the "Remembering Your Spirit" segment in 1998 as a way to challenge viewers to personally apply the lessons learned on each show. Oprah often refers to her show as "my ministry," and examples of her benevolence abound. She gives liberally of her time and money, convincing others to do the same through her Angel Network and the Use Your Life Award. She has funded scholarships at historically black colleges, rescued a local Special Olympics program, written checks to churches, and moved families out of the inner city. She is the national spokeswoman for A Better Chance, a program that gives disadvantaged students opportunities to attend top secondary schools. In 1991, Oprah promoted the National Child Protection Act, also known as the "Oprah Bill," which created a database to track child abusers. Bill Clinton signed the legislation in 1993.

Oprah clearly believes part of her role as a talk show host is to call her audience to some sort of higher plane. The theological nature of that higher plane and her methods for getting there are what sound alarms for many of her Christian critics.

What Does She Believe?

"I like Oprah," says preacher and Bible teacher Brenda Salter McNeil. "I'm a closet groupie, though, because her theology's a little off. But I think she has one of the most positive programs on television." McNeil, founder and president of Overflow Ministries in Chicago and a former regional director for InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, is one of many Christians who admire Oprah as a communicator and humanitarian, but who have reservations about her spiritual beliefs. Oprah's public theology reflects a trend among some African Americans to compile a belief system from several philosophies, McNeil says. "There's a blending that's happening in the African American community now of this kind of New Age, Afrocentric spirituality that has a measure of truth but never forces people into a clear relationship with Jesus Christ."

On a show broadcast last November, Oprah explored the value of spiritual beliefs in the wake of the September 11 tragedy. "Today, whatever it is you believe most deeply, now is the time to embrace it," she told her audience. "I say to people, if you have no faith at this time I don't know what to say to you . …If you don't know what you believe in when you're going through difficult times, then you feel shaky and unbalanced."

But what core beliefs is Oprah turning to now? There are no authorized biographies of Oprah Winfrey, and she declined CT's requests for an interview. Several principles emerge, however, from a close reading of her show, guests who speak on spiritual matters, and other interviews she has given.

Through her discussions with New Age author and thinker Gary Zukav, for instance, Oprah emphasizes that we are more than physical beings. "I believe that life is eternal," she has said. "I believe that it takes on other forms."

She told Zukav, "I am creation's daughter. I am more than my physical self. I am more than the job I do. I am more than the external definitions that I have given myself . …Those are all extensions of who I define myself to be, but ultimately I am Spirit come from the greatest Spirit. I am Spirit."

Through a succession of guests with eclectic religious ties, including Zukav, Carolyn Myss, Marianne Williamson, Iyanla Vanzant, and Deepak Chopra, Oprah's show has normalized a generic spirituality that perceives all religions as equally valid paths to God. The show also presents an á la carte blend of religious concepts, from karmic destiny (Zen Buddhism) to reincarnation (Hinduism).

"There's this assumption [in Oprah's spirituality] that whatever is really true can be found in many different paths," says Elliot Miller, author of A Crash Course on the New Age Movement (Baker, 1999) and editor in chief of Christian Research Journal. "Out of that, there is an effort to create a contemporary spirituality that is suitable to the postmodern temperament."

Miller, who taught a seminar at last year's Cornerstone Festival that analyzed Oprah's beliefs, calls her a representative of the new spirituality that defines postmodernism. "What we're dealing with is sort of amorphous," he says, "because it isn't some religion that is coming in and displacing Christianity. In fact, a lot of people who embrace the new spirituality would say they draw most heavily from the Christian tradition."

So where does Christ fit into the Oprah brand of spirituality? While Oprah herself makes few references to Jesus, if she shares the views of many of her guests, "she would believe that Jesus is like an ascended master, a God-realized teacher, someone who completely expressed God in their life," Miller says.

Consequently, Jesus Christ is not seen as a personal Savior or God incarnate but as a good teacher who shows us how to achieve what he has achieved. This view renders Christian distinctives such as salvation by grace, redemption through the Cross, the Trinity, and the Last Judgment irrelevant.

Still, it is clear that Oprah retains some elements of her Baptist upbringing. Her show has a "churchy" feel, the theme music has a gospel flair, and gospel artists such as Yolanda Adams, BeBe and CeCe Winans, Wintley Phipps, and Donnie McClurkin are occasional guests. Christian professionals such as Stephen Arterburn, author of several books on therapeutic issues, and relationship experts Les and Leslie Parrott have shared their expertise. In her O: The Oprah Magazine monthly column, "What I Know for Sure," Oprah refers frequently to the Bible, her church background, and lessons God has taught her. In earlier interviews, she has spoken about reading the Bible, praying, and meditating daily. She has also said that her faith has sustained her, and spoken of "the absolute responsibility to live our lives as a praise." A People magazine article about Oprah's Personal Growth Summit tour last summer noted that while she refers to a "higher power" on television, at a Raleigh, North Carolina, summit she spoke "with a preacher's confidence of 'the Creator,' 'the Lord,' even 'my blessed Savior.' "

Oprah's Christian heritage informs her show and magazine in more than cosmetic ways, some observers believe. "She has come to understand some deeply biblical principles about life," McNeil says. "In Proverbs it says, 'As a man (or a person) thinks in his heart, so is he.' I think that she and others have come to understand that we participate with God in creating reality. That we can limit ourselves by how we think, and we can also begin to expand our potential by how we think and what we believe."

Too Famous for Church

When Oprah goes to church in Chicago, she has been known to attend Trinity United Church of Christ, located on the city's South Side. Trinity is the largest church in its denomination, with more than 8,000 members, several subsidiary corporations, and an annual budget of about $9 million. It is an Afrocentric church with a membership composed largely of upper middle class blacks. These elements, no doubt, appealed to Oprah's roots in the church, her longtime interest in black history, and her concern for social justice.

According to Trinity's senior pastor Jeremiah Wright, however, Oprah has not attended a service there in the last eight years. When she first came to Trinity in the 1980s, it seemed that she would become an active participant. Says Wright, "She walked the aisle to become a member, publicly claimed us as her church in Ebony magazine, and when I would run into her socially, like at a United Negro College Fund dinner, she would say, 'Here's my pastor!'" But Oprah never completed the membership classes and after awhile her attendance dropped off.

Wright says Oprah had been very active as a member of Bethel AME Church during her years in Baltimore. Mentoring young girls was one of her primary interests at Bethel, and it looked as though she would continue that ministry at Trinity. But then The Oprah Show went national and altered the course of her life.

"Sundays got to be a hassle for her," Wright says. "Everybody came at her with notes, with portfolios, with ideas and requests. It made her coming to church a problem."

Shortly after her show was syndicated in 1986, Oprah spoke about the challenges of being a celebrity in a public worship service: "Last Sunday I was in church, and a deacon tapped me on the knee and asked me for my autograph," she said. "I told him, 'I don't do autographs in church. Jesus is the star here.' "

Wright understands the pressures Oprah faces in public settings, but he has seen other celebrities maintain a commitment to their churches, despite their fame. He thinks there might be other reasons for Oprah's absence from the pew. "I think it is hard for most very wealthy people to be a part of the church," he says. "Somebody who makes $100 a week has no problem tithing. But start making $35 million a year, and you'll want to renegotiate the contract. You don't want to be a part of 'organized religion' at that point. That's a generalized statement, but that's what I've found across the years. The wealthier somebody gets, the more they pull away from the church."

Today Oprah's relationship with Trinity and Jeremiah Wright seems strained. In a column for a recent issue of Black Collegian magazine, Wright mentioned Oprah as an example of African Americans who forget their roots in the church after finding success. "A lot of us do not even like the word faith anymore," he wrote. "We prefer the more chic-sounding word, spirituality! We are caught up in an Oprah-generated mentality and a 12-step vocabulary that prevents us from using the very words and the very bridge that 'brought us over!' "

Oprah Winfrey did not respond to CT's request for comment about the article, but Wright stands by his statement. He is clearly put off by the direction Oprah's faith seems to have taken.

"She has broken with the [traditional faith]," he says. "She now has this sort of 'God is everywhere, God is in me, I don't need to go to church, I don't need to be a part of a body of believers, I can meditate, I can do positive thinking' spirituality. It's a strange gospel. It has nothing to do with the church Jesus Christ founded."

The Seekers' Seeker

On the Oprah set, after the taping of a Lifestyle Makeovers show, a woman stands to thank Oprah "for really helping us bring our paths to where we need to be." Oprah thanks the woman in return. "I could not do what I do if it were not received," she says. "In the earlier years when I really wanted to do this, I couldn't do it. We had to work our way to this point."

As with a pastor and her parishioners, the bond between Oprah and those in her audience is sacred. She understands the magnitude of the power she wields over them and seems to want to use it to guide them toward better lives.

But what does Oprah's appeal to so many Americans, particularly women, tell us about current American spirituality?

First, so-called secular Americans remain spiritually hungry. This may be because so much of our culture is secular. When someone like Oprah comes along and is open about spirituality, and in a winsome way, people are fascinated. Oprah's increased popularity when she became more publicly spiritual is just one evidence of this.

Second, Americans are interested in practical spirituality. "Oprah is concerned with helping us live better and more authentically," says Robert Johnston, professor of theology and culture at Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, California. Brenda Salter McNeil adds: "People today are really looking for a message of salvation that literally has the power to change their lives. Oprah's greatest success is that she's living proof of what she believes."

Indeed, part of Oprah's appeal is that she motivates people to make practical, lasting changes in their lives. Whether she is speaking about diet and exercise, promoting a new book, or hosting the straight-talking Dr. Phil, her gospel is an empowering one: you can change.

Third, Americans yearn for a hopeful spirituality. During one broadcast, a viewer confides that she purchased a pair of Oprah's size-10 shoes at a charity sale and would stand in them, size 7 feet slid toward the front, whenever she felt powerless or small. As she learned more from the show, she said, she didn't need them as often. She has changed. The woman drops her head into her hands, and Oprah dabs at her eyes. Oprah's brand of spirituality encourages and inspires millions.

Fourth, many Americans like to dabble in a variety of belief systems. When the mother of missing congressional intern Chandra Levy told The Washington Times that she was a "Heinz 57 mutt" in her spirituality—drawing from Judaism, Christianity, Buddhism, and other religions—she verbalized a sentiment common to many in Oprah's audience. And Oprah herself has said, "One of the biggest mistakes humans make is to believe there is only one way. Actually, there are many diverse paths leading to what you call God."

None of this is new, of course. Social commentators have noted such American trends since Alexis de Toqueville's Democracy in America (1835). The Church of O merely brings this into focus in the 21st century.

What the Oprah phenomenon also shows, though, is that this brand of spirituality is ultimately unsatisfying. Perhaps the most telling thing about Oprah's role as a spiritual leader to the seeking masses is that she herself is such an ambitious seeker. Indeed, the smorgasbord of religions and ideas that make up her belief system suggest that she still has not found what she's looking for.

The question for Christians is this: What can we do to help Oprah and her disciples find what they are ultimately seeking—the power, grace, and love that can only be found through a personal relationship with Jesus Christ?

The answers are not obvious, but the need to find them is as urgent as ever.

LaTonya Taylor is the editorial resident at Christianity Today.

Copyright © 2002 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere

A ready-to-download Bible Study on this article is available at ChristianBibleStudies.com. These unique Bible studies use articles from current issues of Christianity Today to prompt thought-provoking discussions in adult Sunday school classes or small groups.

Also appearing on our site today:

Oprah's GurusFour popular New Age voices featured on Winfrey's television show and in her magazine, O.

Oprah.com is the place for all things Oprah: The Oprah Show, O magazine, Oprah's Book Club, and The Angel Network. The site tackles many of the same issues as the show with advice on finances, mind and body, "your spirit," and food. Even Dr. Phil has his one page.

Recent articles on Oprah's spirituality include:

The feel-good spirituality of Oprah — Our Sunday Visitor (Jan. 13, 2002)

Is Oprah Winfrey a threat to national security? — National Review Online (Oct. 8, 2002)

CNN Chicago has an archive of resources and articles on the 1998 court battle between Oprah and the Texas cattlemen.

Members of the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod were upset that one pastor, David Benke, attended the September 23 Yankee Stadium event hosted by Oprah. Charges against the denomination's president for letting Benke attend the inter-faith event were dropped in December.

Christianity Today interviewed several Christian leaders to find under what circumstances it is appropriate for Christians to worship or pray with non-Christians in 'Praying in Their Midst.' A recent Christianity Today editorial also looked at "The Interfaith Public Square."

Vicki Abt's Coming After Oprah : Cultural Fallout in the Age of the TV Talk Show and Elliot Miller's A Crash Course on the New Age Movement are available at Amazon.com.

Abt's The Shameless World of Phil, Sally, and Oprah: Television Talk Shows and the Deconstruction of Society is available as a PDF document.