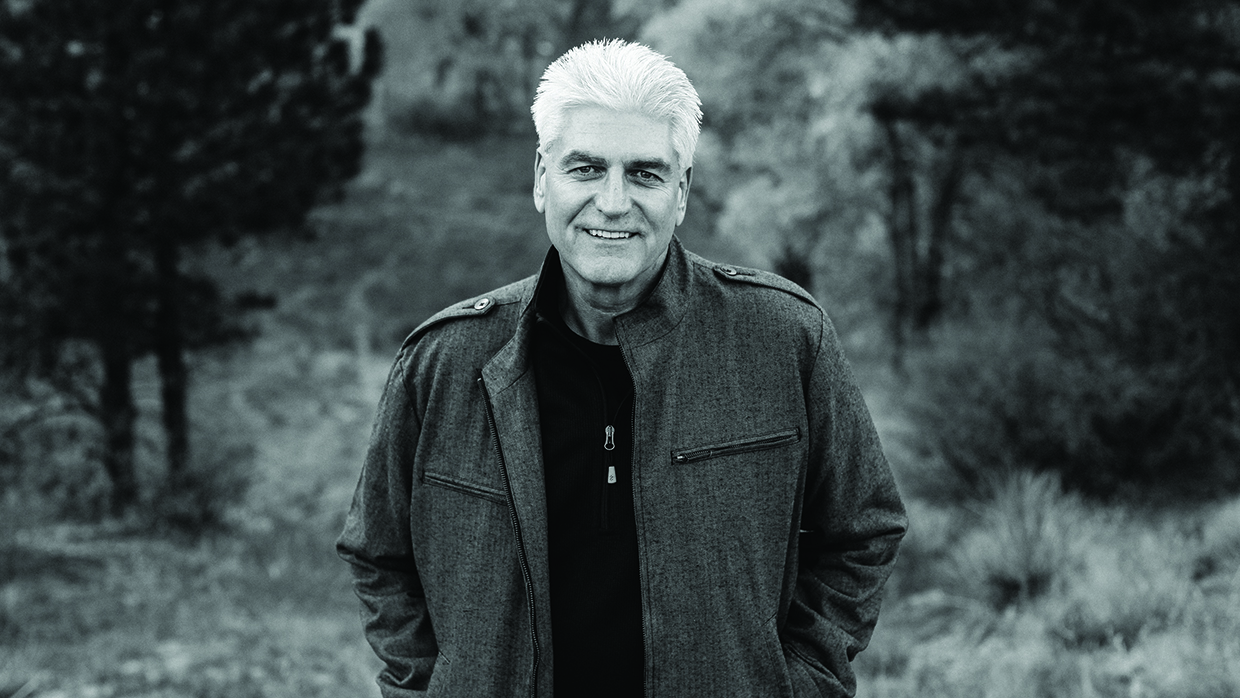

As president of Peacemaker Ministries—which has worked with hundreds of churches to quell disputes using biblical principles—Dale Pyne has seen his fair share of pastoral failings. He spoke with CT editor Mark Galli about what pressures tempt pastors to fall, and what they need to finish their ministry with a clean slate.

Aside from a pastor’s personal weaknesses, what cultural forces make it harder for pastors to stay true in their calls?

We have a cultural tendency to elevate leaders. Maybe it’s because they have an extraordinary education or a title or a position. Maybe it is because they have had a great deal of success in the growth of their church, or as an author or speaker. Whatever the reason, we’re creating minigods in our minds and hearts. That creates expectations in leaders, and expectations are the foundations for disappointment.

What does that look like in a local church?

Maybe the pastor receives disproportionately large gifts compared to what’s given to associates or other staff. Or the senior pastor is seen as the person that we all go to. It’s people saying, “The pastor sat at my table,” or, “The pastor was over at my house.” As if the pastor is a movie star or sports figure.

I don’t know how many times in Peacemaker’s work, after coming in to help a church, I’ve heard elders say, “I wanted to say something, but I thought, Who am I?” We elevate pastors to a place where we feel they know so much more than we do, so we don’t hold them accountable to some fundamental issues.

We put them on a pedestal that gets taller and taller. When the pedestal starts to totter, the pastor doesn’t have anywhere to go. If he realized that he had a sin problem and desired to address or confess it, his place on the pedestal sometimes facilitates pride and fear of man. So they die in silence and pain. And they fall. And because the pedestal is now so high, they hit the ground hard.

What other cultural attitudes pressure pastors?

You maybe have elders saying, “Listen, we’re shrinking. We have problems. We have people leaving the church.” Almost every church model I’ve seen focuses on coming to Christ, growing in Christ, and serving others as the central goals. But when we get behind closed doors, we count attendance. There is pressure to inflate or puff the numbers.

Peter Drucker, the management guru in the 1980s, said you cannot manage what you cannot measure. But if we start managing shepherding by the numbers, we’re going to lose shepherding, and we’re going to focus on the numbers. That’s where the breakdown often starts.

But isn’t a pastor supposed to lead, to be someone people look up to and follow, to make a difference for the church?

The qualification for leadership is not perfection. The main qualification for leadership is transparency and humility.

It is appropriate to look to the pastor as a leader. They are called, qualified, and ordained to be leaders. But the qualification for leadership is not full sanctification or perfection (1 Tim. 3 and Titus 1). Pastors walking in the light are going to exhibit the fruit of the Spirit (Gal. 5:22-23 and Eph. 4:1-2, 25). Pastors who exhibit humility and live transparently are leading others by example. Leaders who misrepresent who they are to their congregation create distance and discourage connection. Jesus was perfect, pastors are not. Congregants need to hear this from their pastor.

How does a pastor develop humility to resist the idol worship and the pressure to perform?

We all must remember who we are in Christ and who we are not without him. We must genuinely redirect the glory and praise given us to the Lord (1 Cor. 10:31). Pastors are no different than you and I. They can only resist the temptation for self-glorification by staying in the Word, on their knees, and getting connected in a high-integrity accountability relationship with one or several spiritually mature individuals. It would bless pastors if church leaders who oversee pastors know who the pastor is connected with and could establish a way to verify ongoing accountability without compromising confidentiality.

There are different levels of accountability, of course. The kind I’m speaking of is personal. It’s accountability for the leader’s personal relationships and life. So if a pastor is having moral temptations, he needs to be able to go to someone in confidence. The pastor needs to have people to go to. And they must trust that the relationship is a confidential one.

In addition, I’d encourage pastors to be vulnerable from the pulpit. When I’m speaking and I tell a third-party story, people might say, “That’s very interesting.” But when I tell a story that involves me and my own sin, then people say, “Wow, here is Dale. He’s a leader, and I respect him. But he’s telling me that he’s just like me.”

If we’re too busy denying and protecting and putting on a church face, then the congregation perceives that the pastor has it all together. We say to ourselves, Wow, I am so far from that pastor. I am unworthy. Why isn’t God working in me the way God’s working in him? The people start to elevate them. It’s not all about the pastor, but that transparency releases the congregation. It helps the pastor be real. And releases the congregant to accept who they are and pursue hope in Christ.