In this series

Pastor Edward Awabdeh had just finished serving Communion at the Evangelical Christian Alliance Church when he noticed members fiddling with their phones and whispering nervously to their neighbors. Many in the Damascus, Syria, church had received notifications of a suicide bombing at the Mar Elias Greek Orthodox church, located only 15 minutes away.

Syrian security forces suddenly entered from the rear of the church and evacuated the congregation within a few minutes. But even as congregants filed out peacefully, many feared for their friends’ and relatives’ safety at Mar Elias, where they learned that the June 22 bombing last year had killed 22 Christians and wounded at least 60 others.

“This was our hardest day,” Awabdeh said. “But most concerning is the general atmosphere of extremism [in the country].”

Persecution monitor Open Doors agrees. In the 2026 edition of its annual World Watch List (WWL), the nonprofit listed Syria at No. 6, up from last year’s ranking of No. 18. The country is the only newcomer to the top 10 most dangerous places to be a Christian and received a near-maximum score of 90 in Open Doors’ methodology.

In Open Doors’ previous reporting cycle, which ends each September, zero Syrian Christians died for faith-related reasons. For the 2026 report, Open Doors verified at least 27 deaths of believers.

The fall of the Assad regime in Syria occurred in December 2024. Shortly after, Ahmad al-Sharaa, the leader of the rebel coalition and head of the jihadist group Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) appointed himself as the country’s interim president and established Islamic jurisprudence as the main source of legislation in the transitional constitution.

Open Doors stated that power remains fragmented in the country, leaving space for extremists to harass Christians. Fear prevails among the few Christians who remain in the northwest city of Idlib, where the HTS base also contains ISIS cells and a Turkish military presence, as well as in central Syria due to a lack of local security and extremist intimidation.

In the larger cities of Damascus and Aleppo, Islamist actors have called for conversion to Islam through trucks laden with loudspeakers in Christian neighborhoods. They have placed posters on churches demanding payment of the sharia-mandated jizyah tax (historically levied on non-Muslims) for those who refuse.

The situation for Christians is more tolerable in Syria’s coastland regions and the Kurdish-ruled northeast, Open Doors stated. Still, Syrian authorities closed 14 Christian schools in the northeast that refused to adopt a new Kurdish curriculum, denying education to thousands of students.

Awabdeh has hope for Syria. Evangelicals enjoy “ten times” more freedom now than under Assad, he said. Authorities sent security forces to guard all Christian areas during Christmas, and the head of police in Damascus visited his church to offer holiday greetings. Officials also recently gave permission to build a community center on Alliance-owned land in the capital, which the previous regime had denied for more than three decades.

Yet Awabdeh remains troubled that the government is not reining in extremism. Officials say all the right things about minorities’ rights, he says, but there was little accountability following the Syrian forces’ massacre of Alawites last March and during armed militias’ killings of Druze Muslims last July.

In the southwest region of Druze-majority Sweida, armed men entered the apartment of one of Awabdeh’s church members and held him at gunpoint. They stole everything and destroyed all the Christian symbols in his home. A moderate Muslim shaykh told Awabdeh that some Islamic militants believe they have the right to loot non-Muslim properties.

Syrian Christian emigration continues to grow. Open Doors estimates that only 300,000 believers remain, down from a pre-2011 total of 1.5 to 2 million, which was 10 percent of the population at the time.

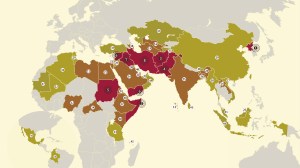

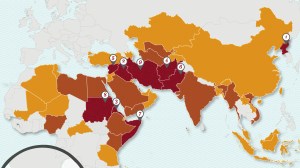

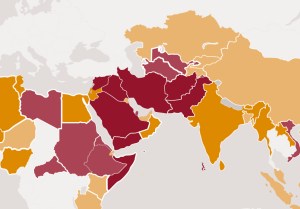

Globally, more than 388 million Christians live in nations with high levels of persecution or discrimination for their faith. That’s 1 in 7 Christians worldwide, including 1 in 5 believers in Africa, 2 in 5 in Asia, and 1 in 12 in Latin America. The total number rose by 8 million since last year, reflecting a steady increase over time. Per the 2019 WWL, 1 in 9 Christians worldwide resided in high persecuting countries.

The dramatic rise in Syria’s rank on the WWL should not distract from persistent persecution in the rest of the world. Open Doors noted two broad trends in particular: fragile governments and state-induced isolation.

Within the past 5 years, 5 of the 14 sub-Saharan African countries on the WWL have overthrown their governments and two have suspended their constitutions. In the democratic nations of Nigeria and Ethiopia, jihadist and rebel groups prevent the state from extending security and stability throughout its territory.

As a result of similar fragile governments elsewhere, Open Doors marks “Islamic oppression” and “organized corruption and crime” as two of the top three drivers of persecution in 10 of those 14 nations.

In the past decade, the average persecution score for the sub-Saharan region has increased from 68 to 78 out of a scale of 100, while the violence score (1 of 6 markers tracked by the list) has increased from 49 to 88 percent of the total category. This includes killings, detentions without a proper trial, abductions, and property destruction.

Ten years ago, 6 sub-Saharan nations ranked among the 20 most violent countries for Christians worldwide. This year’s list ranks 12 countries from the region in the top 20, including the only three with a maximum score: Sudan, Nigeria, and Mali.

Sudan (No. 4) rose one place in this year’s list due to violence directed at Christians. The civil war, ongoing since 2023, has displaced nearly 10 million people, equal to the population of Greater London or Bangkok. Nationwide, the conflict has damaged hundreds of churches, with Christians targeted in the Darfur, Blue Nile, Nuba Mountain, and capital regions.

The rebel Rapid Support Forces in Sudan, which held much of the capital of Khartoum for nearly two years, destroyed several Christian schools and churches, including the Sudan Presbyterian Evangelical Church and the Evangelical Church in the Omdurman neighborhood. After the country’s national army regained control last March, it proceeded to bulldoze a Pentecostal church.

Yet Nigeria, ranked No. 7, attracted global attention last year when US president Donald Trump rebuked the nation and threatened military action over the persecution of Christians. Listed in the top 10 since 2021 and registering a maximum violence score for eight consecutive years, Nigeria suffers from farmer-herder land conflict mixed with religious intolerance and jihadist oppression.

While experts dispute the root causes of violence against believers, Nigeria recorded the overwhelming majority of Christians killed because of their faith in the 2026 WWL, with 3,490 deaths out of 4,849. Fellow sub-Saharan nations followed, with the Democratic Republic of Congo (No. 29) tallying 339, and Burkina Faso (No. 16) with 150.

However, not all persecution comes from Muslim sources. In Ethiopia (No. 36), the Orthodox Church, which is historically linked to state power, put pressure on Protestant communities that often face hostility at the local level. Despite a 2022 truce signed with the government, armed groups in the regions of Amhara and Oromia burned, demolished, or looted 25 churches, said Open Doors.

Open Doors highlighted other African countries for its second trend—government surveillance and oppression. The overall score for Algeria (No. 20) has increased 7 points to 77 since 2021. The government’s systematic closures of churches have resulted in an estimated three-quarters of Algerian believers no longer being part of an organized Christian community, Open Doors stated. Believers who meet privately to worship continue to risk arrest.

But the highest-ranked example comes from China (No. 17). Despite registering a score of 79, this increase to its all-time high did not result from any change in the level of violence. Instead, pressure on the church increased from the publication and enforcement of new regulations on the use of the internet and social media.

Preaching can only be hosted on registered websites, through the official Catholic and Protestant associations. Church leaders must support the Communist Party and a socialist system while refraining from fundraising, doing outreach to youth, and distributing Bible apps and religious material.

The new rules in China fit a pattern of increased regulation since 2018 and coincide with repression against previously tolerated independent churches, Open Doors said. Some of these larger fellowships now meet quietly in groups of only 10 to 20 believers. Government officials may accuse unregistered house church pastors of “provoking trouble,” and these pastors face suspicions of fraud if they collect offerings.

Despite the lessening of violence levels in some still-oppressive nations, the statistics collected by Open Doors remain disturbingly high globally. Christians killed for their faith in countries including Nigeria increased by nearly 400 cases compared to the previous reporting period.

Acts of violence also forced Christians to leave their homes in search of safety elsewhere. In the 2026 WWL, Open Doors recorded 224,129 Christians who were internally displaced or became refugees, in comparison with 209,771 cases in the prior reporting period. Believers from Nigeria, Myanmar (No. 14), and Cameroon (No. 37) suffered the most this way.

The number of cases of Christians who have been physically or mentally abused (including beatings and death threats) for faith-related reasons increased from 54,780 to 67,843 in the 2026 WWL. Nigeria, Pakistan (No. 8), and India (No. 12) had the most instances of such abuse. The total number of Christians sentenced to prison, labor camps, or mental hospitals for their faith increased from 1,140 to 1,298, with India, Bangladesh (No. 33), and Eritrea (No. 5) leading the list.

Meanwhile, the number of Christians raped or sexually harassed for faith-related reasons rose from 3,123 to 4,055, with Nigeria, Congo, and Syria as main offenders. The report acknowledged the challenge of gathering these numbers, given victims’ trauma and cultural taboos.

Another sensitive data point: the number of forced marriages of Christians to non-Christians. Open Doors reported that this figure increased from 821 to 1,147, with Nigeria, Pakistan, and the Central African Republic (No. 22) as the top three.

Other indications of violence went down in the newest reporting period. Attacks on houses, shops, businesses, or other property belonging to Christians fell from 28,368 to 25,794 cases, with Nigeria, Sudan, and South Sudan (ranked outside the top 50) topping the chart. Attacks on church properties declined substantially from 7,679 to 3,632, with Nigeria, China, and Niger (No. 26) the most prominent offenders. The number of abducted Christians decreased from 3,775 to 3,302, with Nigeria, Sudan, and Mozambique the most dangerous for that category.

In many cases, figures cannot be measured precisely, so Open Doors sometimes reports round figures of 10, 100, 1,000, 10,000, and 100,000, depending on the situation. Its researchers emphasized that estimates are conservative and represent the “absolute minimum” of attacks and atrocities, meaning the actual figures are likely much higher.

Open Doors also described improving trends for Christians in certain countries on the 2026 WWL. Muslim-majority Bangladesh fell to No. 33 from No. 24 because of a 20 percent reduction in its violence score, following the relative calm after the 2024 overthrow of its government. The country’s interim prime minister, Muhammad Yunus, has also made several positive statements about religious freedom, though his commitment may be tested during next month’s elections.

In Malaysia, ranked just outside the top 50 most dangerous nations in which to be a Christian, the high court issued a groundbreaking ruling that recognized the role of police forces in the 2017 abduction of pastor Raymond Koh. The court ordered the government to reopen the investigation and pay a fine for every day of Koh’s disappearance, which has now reached a total of over $7 million USD.

Finally, although religious freedom conditions are not improving substantially in Cuba (No. 24), Mexico (No. 30), Nicaragua (No. 32), or Colombia (No. 47), there has been an increase in local and global religious freedom advocacy on behalf of believers in these countries. Churches in these contexts “show remarkable resilience and creativity” in serving their vulnerable populations, the Open Doors report noted.

CT previously reported the WWL rankings for 2025, 2024, 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, and 2012, as well as a spotlight in 2010 on where it’s hardest to believe. CT also asked experts in 2017 whether the United States belongs on persecution lists and compiled the most-read stories of the persecuted church in 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, and 2015.

Read Open Doors’ full report on the 2026 World Watch List here.

Methodology

Open Doors scores each nation on six components, and each category can receive a maximum score of 16.7 for a maximum total score of 100. Researchers consider a score of more than 40 points as high.

Their methodology takes into account violence as well the pressure to reject their faith that believers experience from neighbors, friends, extended family, and society as a whole. The total score is determined based on answers from an extensive questionnaire.

- Private life: the inner life of a Christian and his or her freedom of thought and conscience.

“How free has a Christian been to relate to God one-on-one in his/her own private space?” - Family life: pertaining to the nuclear and extended family of a Christian.

“How free has a Christian been to live his/her Christian convictions within the circle of the family, and how free have Christian families been to conduct their family life in a Christian way?” - Community life: the interactions Christians have with their respective local communities outside their families.

“How free have Christians been individually and collectively to live their Christian convictions within the local community? How much pressure has the community put on Christians by acts of discrimination, harassment or any other form of persecution?” - National life: the interaction between Christians and the nations they live in. This includes rights and laws, the justice system, the state, and other institutions.

“How free have Christians been individually and collectively to live their Christian convictions beyond their local community? How much pressure has the legal system put on Christians? How much pressure have agents of supra-local life put on Christians by acts of misinformation, discrimination, harassment or any other form of persecution?” - Church life: the collective exercise of freedom of thought and conscience, particularly as regards uniting with fellow Christians in worship, service, and the public expression of their faith without undue interference.

“How have restrictions, discrimination, harassment or other forms of persecution infringed upon these rights and this collective life of Christian churches, organizations and institutions?” - Violence: deprivation of physical freedom, serious physical or mental harm to Christians, or serious damage to their property. This is a category that can affect or inhibit relationships in all other areas of life.

“How many cases of such violence have there been?”

Additional reporting by Sofía Castillo