“Science is not like God. Science is all fact. God is a myth concocted by primitive men,” my professor thundered during a biochemistry lecture. According to him, God was like a white-bearded magician sitting on the clouds with his magic wand, but science governed the material world and reality.

He said science served as the ultimate arbiter of truth and people had created God from their imaginations. To him, the time had come to abandon God and religion. Although faith might have been useful in the dark ages, he said, we now had a duty as civilized men to embrace truth (science).

These words sent shivers down my spine. I had never heard such brazen attacks on the existence of God. I felt stunned and had no response to his arguments.

I had believed in God all my life—or at least as long as I could recall—but now someone more learned and well-read was challenging that belief. My homeland, Nigeria, is a very religious country. Muslims and Christians each make up about half the population, with a handful of people practicing traditional African religions.

Because belief in God and in the supernatural is common, my first encounter with atheism happened in college. In fact, that was the first time I had even heard the word atheist—and I had no idea what it meant.

Suddenly I had to face the question of whether Christianity was true. If science was at odds with God, creation was a myth, miracles were impossible, and the resurrection of Jesus was a fable, then my foundations would crumble. I would have to probe deeper, to discover ultimate reality.

In 1993, I had the immense privilege of being born to Christian parents who placed faith at the core of their lives and our family. As I grew up, we gathered for regular morning devotions with Bible reading and prayer. Sundays were the heartbeat of our week—a time for worship, reflection, and family.

Our church met in a modest room with a cluster of wooden chairs arranged in rows, used for school programs during weekdays. As I sat through the sermon, my mother gave me small, oval, chocolate-flavored biscuits she had tucked into her purse. I munched them in quiet joy as the pastor preached with words that seemed big and distant to my young mind.

As an 11-year-old, I arrived at Holy Child Catholic Secondary School, a boarding school, clutching my suitcases. The school’s strict routine and strange practices clashed with my Protestant upbringing and personal faith. Bells clanged through the dormitories daily at 5 a.m., then came daily Mass, Latin hymns, rosaries, stations of the cross, and the scent of incense and beeswax candles.

The solemn liturgy the priests chanted captivated me. But as the priests and fellow students offered prayers to Mary and other saints, I wondered: If Jesus is “the only mediator between God and man,” why pray to anyone else? Why appeal to Mary to save those in purgatory?

Although all my life I had known the name of Jesus, I relied on the faith of my parents. Neither attending church nor going to Catholic school would save me. I had to make my faith personal by trusting in Jesus Christ alone. So in 2013, God used my atheist professor to cause me to ask, Is this faith mine or my parents? Do I really believe in this Jesus? Do I know him? Am I known by him?

I needed to know the truth. This led me to Christian apologetics and to a discovery of past and present writers such as C. S. Lewis, R. C. Sproul, Stephen Meyer, John Lennox, and Nancy Pearcey. I devoured their works.

They taught me that science and belief in God aren’t at odds—the supposed conflict is a historic and philosophical myth. In fact, many of the fathers of modern science saw their faith in God as a motivation to pursue science and truth.

“Men became scientific because they expected Law in Nature, and they expected Law in Nature because they believed in a Legislator,” Lewis wrote in Miracles. Real science requires us to assume the universe has regularities or laws we can rely on. This is only possible in a world with an ultimate lawgiver, God.

The apostle Paul declares in Romans 1 that creation and the conscience provide evidence for God. As his creatures, we can know enough to lead us to worship and honor him, so we are without excuse when we don’t (Rom. 1:19–20).

As I wrestled with my questions, I often sat in pastor Ronald Kalifungwa’s study in Lusaka, Zambia. The scent of old and new books, neatly arranged in shelves, enveloped the room. He asked me probing questions and helped me consider whether I had anchored my worldview in Scripture or culture.

Pastor Kalifungwa showed me that Christians and non-Christians may encounter the same facts—say a scientist’s lab results—but our worldviews about human nature, origins, and purpose shape how we interpret them. Worldview influences how we see everything—politics, ethics, science, even communication. My atheistic professor had promoted scientism—the idea that science is the ultimate way to truth—a new idea in Africa.

Later, in a November morning in 2017, I attended the first meeting of the Atheist Society of Nigeria Convention—entitled “The Road to Reason”—at the University of Lagos in Akoka, Yaba. Budding atheists, many of whom had grown up in Christian homes, met to express their frustration with what they saw as the hypocrisy and irrationality of religious people.

I remember wanting to grab each of them and say that although they are right to criticize hypocrisy, Jesus is the one they must turn to. We have nowhere else to go—not science, not atheism, not Mary, not the saints. Nowhere to go but Jesus. He has “the words of eternal life” (John 6:67–69).

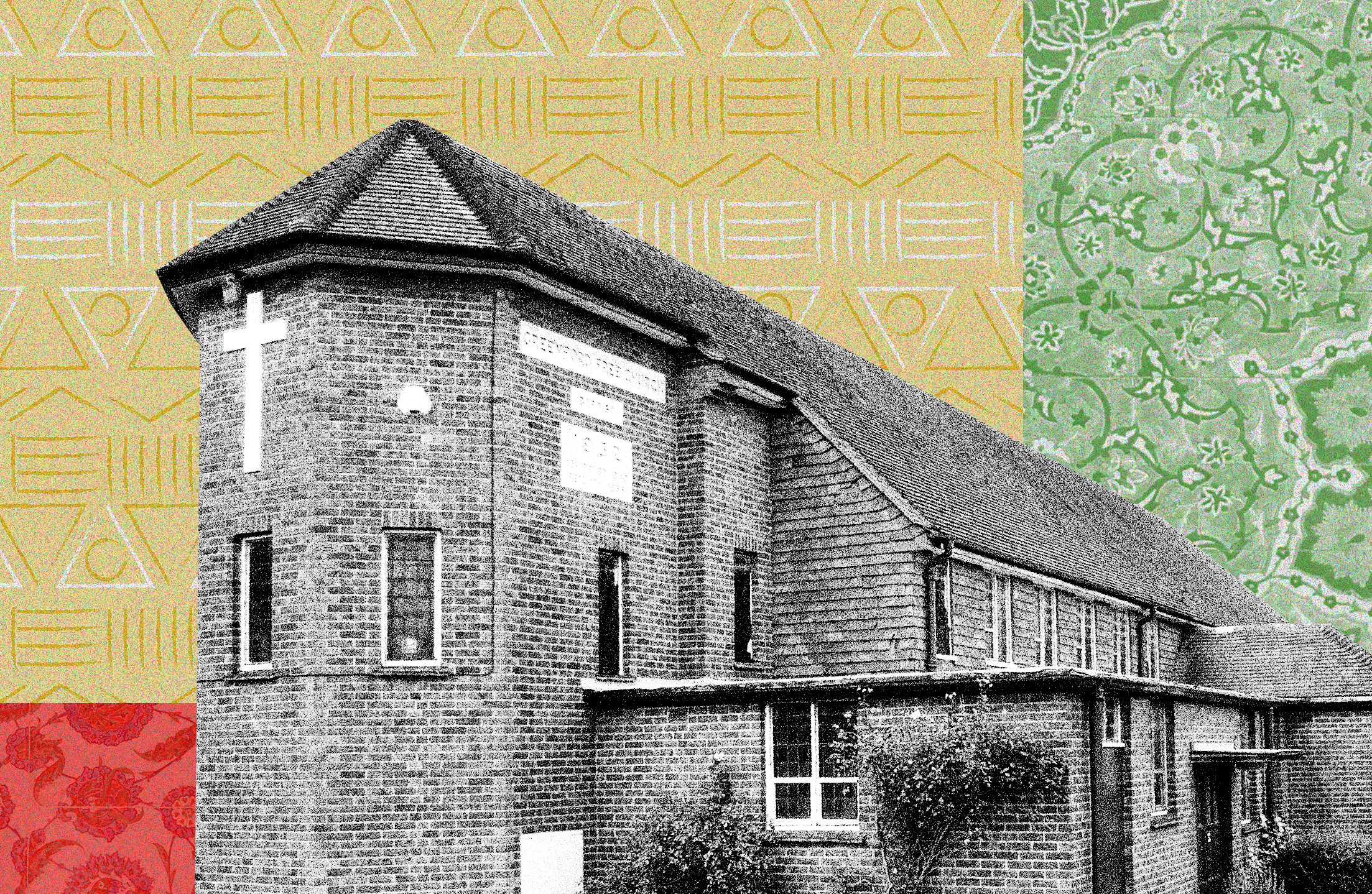

In 2018, I moved to Cyprus to pursue my master’s degree and stepped into Lefkoşa Protestant Church, a Reformed Baptist congregation that became my home until 2023. There I discovered the highs and lows of the Christian life: moments when we feel and know God’s presence, and times of discouragement when he feels distant. As I listened and observed struggling church members, their fears and hopes transformed me. Now back in Nigeria, I still don’t have immediate answers to pain or to every question, but I know the cross of Christ provides the only real resolution.

Emmanuel Nwachukwu is a freelance writer and the cofounder of The Late Wire, a media and apologetics organization that promotes Christianity in the Nigerian public square.