In our family, holiday movies and TV specials feature in our living room throughout the month of December. And after all these years, nestled on the couch with our four kids in front of the screen, we have observed a common theme: Christmas needs to be saved.

The “Saving Christmas” trope can take on many iterations, but its familiar pattern often begins with a crisis, sometimes dire enough to raise that most unthinkable of prospects: the cancellation of Christmas festivities.

Usually, the cause or condition of inevitable holiday disaster is some form of doubt, unbelief, or seasonal cynicism: Christmas skepticism is on the rise as the general populace is distracted and disillusioned! Belief in Santa has reached an alarming low, and his sleigh needs more Christmas spirit and holiday cheer for its propulsion!

With the joy of the season often in danger and under threat, the Christmas of holiday movies is a fragile, vulnerable thing: embattled, cancellable, and in need of rescue. The basic plot of these films and shows is born out of the fundamental conviction that Christmas needs a savior.

As a result, their main characters must rise to this very challenge. The job of saving Christmas is up to us. We can do it! And all this is done primarily through an exercise of faith. That is, a belief in magic and seasonal ideals like hope and kindness—as well as in Santa and the certainty that good ole’ St. Nick will arrive just in time and against all odds.

But equally threatening to the Christmas of holidays films and specials is self-doubt in our own abilities and personal resources. Protagonists must look within themselves and rediscover their inner strength and a renewed capacity for holiday joy and good cheer. We just need to dig deep into our hearts and believe—in Christmas magic, in Santa, and especially in ourselves. And by the time the credits roll to festive music, the holidays will have been saved!

These films and holiday specials engage with grand theological themes like salvation, faith, hope, and love. Yet the screenwriters seem bound to some unspoken contractual agreement with secularism to uncouple these ideals from the divine, anchoring them instead within human capacity and ability. Though some assistance from magic is clearly allowable under the terms and conditions, where else would secular folks look first except within?

For Christian audiences, there’s a distinct irony to the “saving Christmas” theme. Christmas is indeed about salvation, but not its own. Christmas is about our salvation, the rescue of its would-be heroes. Christmas is not in crisis; it solves the crisis of our human condition.

To be clear, I am not calling for Christians to be theological Grinches—sitting in front of the TV with our arms crossed, grumbling over Hollywood’s misappropriation of a Christian celebration. Convictions may vary, of course, but I still think we can have fun with pop culture’s seasonal productions even if we cringe a bit while we laugh.

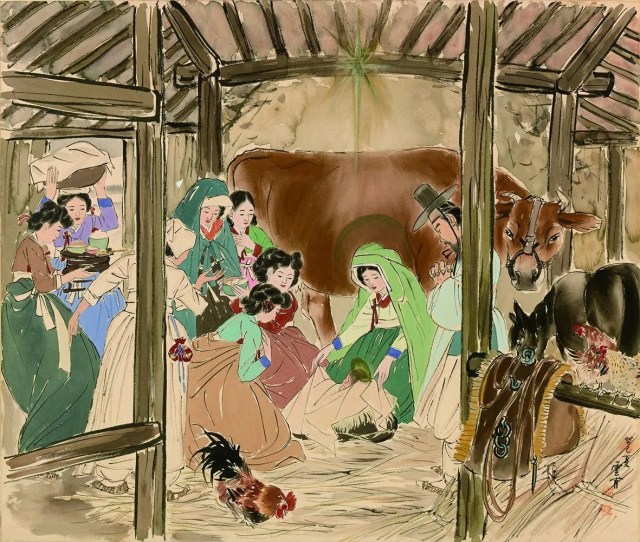

It is also true that the first Christmas seemed imperiled and fragile in those biblical accounts of Jesus’ birth. Matthew, in particular, draws us to the edge of our seats with its close calls and near misses, beginning with the surprising scandal of a pregnant virgin and the serious threat of early Advent antagonists. The unspeakable violence of Herod the Great—a foe far darker than Scrooge and more powerful than today’s panoply of “bad Santas”—is enough to remind us that the original screenplay is not family friendly.

Our present experience of Christmas might also need to be rescued. Cynics like C.S. Lewis remind us of the ways our culture has distracted us from the more sacred things of the season. And while we can strive to push back against empty sentimentalism and rabid consumerism of the holiday, we still choose to celebrate and participate in the vicarious joy of others.

This is also a time of year when many of us find our griefs sharpened, our anxieties heightened, and our loneliness more dismal. Yet whether we have lost loved ones or we are feeling estranged from our family or faith, we are reminded, as Tim Challies writes for CT, that “Christmas is a happy day for broken hearts,” because we do not grieve without hope.

That said, Christmas itself does not need a savior. ’Tis not the season for humans rescuing Christmas but of celebrating God’s rescue of humans through Christ his Son. Christmas does not need saving—we do.

I have looked deep within myself, and what I have found is not enough. Amid all the darkness and deficits, I may still strive to persevere and rise to some challenges. But I lack the necessary and sufficient resources for the kind of self-rescue that counts. I am not equipped for self-salvation. I need someone from outside my failing capacities and limited abilities.

This holiday—holy day—recognizes that unto us has been born “in the city of David a Savior, who is Christ the Lord” (Luke 2:11, ESV), one whose return we await in a forthcoming sequel: “This same Jesus, who has been taken from you into heaven, will come back in the same way you have seen him go into heaven” (Acts 1:11).

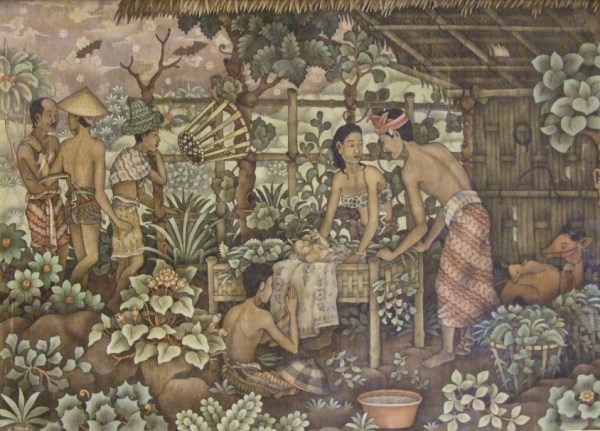

The Incarnation of Christ was an interruption, an intrusion. That interruption was gentle—the Word became newborn flesh, arriving in helplessness and vulnerability. And the intrusion was loving—“for God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son” (John 3:16).

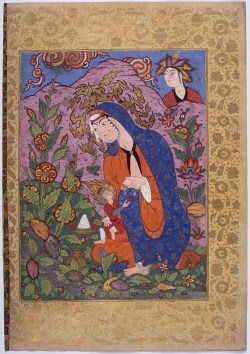

Christmas celebrates an eternal God crossing the threshold of a temporal world. It announces the arrival of a heavenly outsider—of Someone “other” and divine who appeared on an ugly scene to save a fallen humanity. Christ’s Incarnation is a divine immigration, of God coming ashore to knock on our door.

Christmas was the stage entrance of the only Savior who could address the real crises at hand of our human failure, disordered creation, and dysfunctional societies. And we did not write his script, nor did we cue his entrance.

Christmas does not need saving. But when we open that door, we find our own salvation. Then the weary world rejoices—even while eagerly awaiting its eternal conclusion.

Andrew Byers is lecturer in New Testament at Ridley Hall, University of Cambridge.