Our culture has a favorite moniker for people who talk about holidays—especially Christmas—the way I do: Scrooge.

I’ve heard it many times, usually in response to my grumbling about the hassles of hanging decorations and sitting through Christmas pageants. That, or taking kids to holiday markets, which for some reason always seem to be held outside, in the cold and dark, in evening hours—during which the youngest, and therefore most eager, attendees absolutely cannot hang.

I grumble most of all about the presents, comestibles aside. Giving presents is nice enough, and receiving them can be too, but the cleaning always gets you in the end. Truly I tell you, the tree and the Advent calendar will pass away, but the 85 stuffed animals and toy trucks that the grandparents insisted on sending will remain underfoot for months—years!—to come.

Perhaps I shouldn’t be grumbling, but I will say that I’m in good company in my discontent with what C. S. Lewis called the “Exmas Rush,” which distracts our minds “from sacred things” and deceives in its promise of merriment. With Lewis, I reject the idea of any duty to “buy and receive masses of junk every winter,” and, like many other Christians, I could do without many of the extra events and obligations.

For all that, I do not adopt the Scrooge name for myself. After all, it’s not that I’m opposed to Christmas; certainly, I’m not opposed to remembering the Incarnation. It’s just that I’d skip most of the associated fuss if left to my own devices. I prefer to borrow language from the apostle Paul, who observed to the Romans that while “one person considers one day more sacred than another,” “another considers every day alike” (14:5).

That’s me—or would be me, if I could get away with it. Yet, at the same time, I do have a sort of vicarious joy in the Christmas season. While I tend to consider every day alike, others do not, and so I see this as a chance to rejoice with those who are rejoicing (Rom. 12:15), to glory in varying sacred traditions, handiwork, and enthusiasm of the saints.

The holidays Paul had in mind, of course, were not Christian celebrations like Christmas. He was thinking of Jewish Sabbaths and festivals, because the Roman church—as the early church father Ambrosiaster put it—had “embraced the faith of Christ, albeit according to the Jewish rite.”

By the time Paul wrote, some Christians in Rome were Gentiles. But the Roman church was most likely founded, argues scholar Douglas Moo in his commentary on Romans, when “Roman Jews, who were converted on the day of Pentecost in Jerusalem (see Acts 2:10), brought their faith in Jesus as the Messiah back with them to their home synagogues.”

Because of this, some Roman Christians (Jewish and Gentile alike) still believed themselves to be “bound by certain ritual requirements of the Mosaic law,” Moo explains, including “major religious festivals.”

This is the context for Romans’ extensive discussion of the Jewish people’s status concerning Christ’s salvation (see chapters 9–11). But while Paul is usually committed to mounting precise arguments when it comes to matters of faith, sin, and righteousness, his position on religious holidays echoes an ambivalence I can recognize and appreciate (see also 1 Cor. 9:19–23). People have different instincts and convictions on this, he says, and everyone “should be fully convinced in their own mind” (Rom. 14:5).

It seems to me that what ultimately matters is not so much how you handle these days as how you interact with God and your neighbor along the way. “Whoever regards one day as special does so to the Lord,” Paul says, but whoever abstains from celebrating also “does so to the Lord and gives thanks to God. For none of us lives for ourselves alone, and none of us dies for ourselves alone” (14:6–7).

And whatever we do about holidays, Paul adds, doing it “to the Lord” significantly means doing it without contempt for fellow Christians who do otherwise (14:10). In fact, as much as he approves of following one’s own inclinations here (14:5, 22), Paul equally encourages us to abandon them if that’s what is required to love our neighbors well: “Let us therefore make every effort,” he writes, “to do what leads to peace and to mutual edification” (14:19).

Christmas celebrations don’t raise the same theological and cultural questions as the days Paul’s first audience was considering. Yet his call to peace and mutual edification seems equally apt. With Lewis, I find many trappings of Christmas to be more inconvenient than worthwhile. That said, I don’t have to make much effort at all to see the hope they bring to others, to appreciate the hard work and care of handing down traditions generation by generation, year by year.

This joy is no less real for being vicarious. Think of Paul’s anticipation of joy to see Timothy’s sincere faith (2 Tim. 1:4–5) or John’s joy “to find some of your children walking in the truth, just as the Father commanded us” (2 John 1:4).

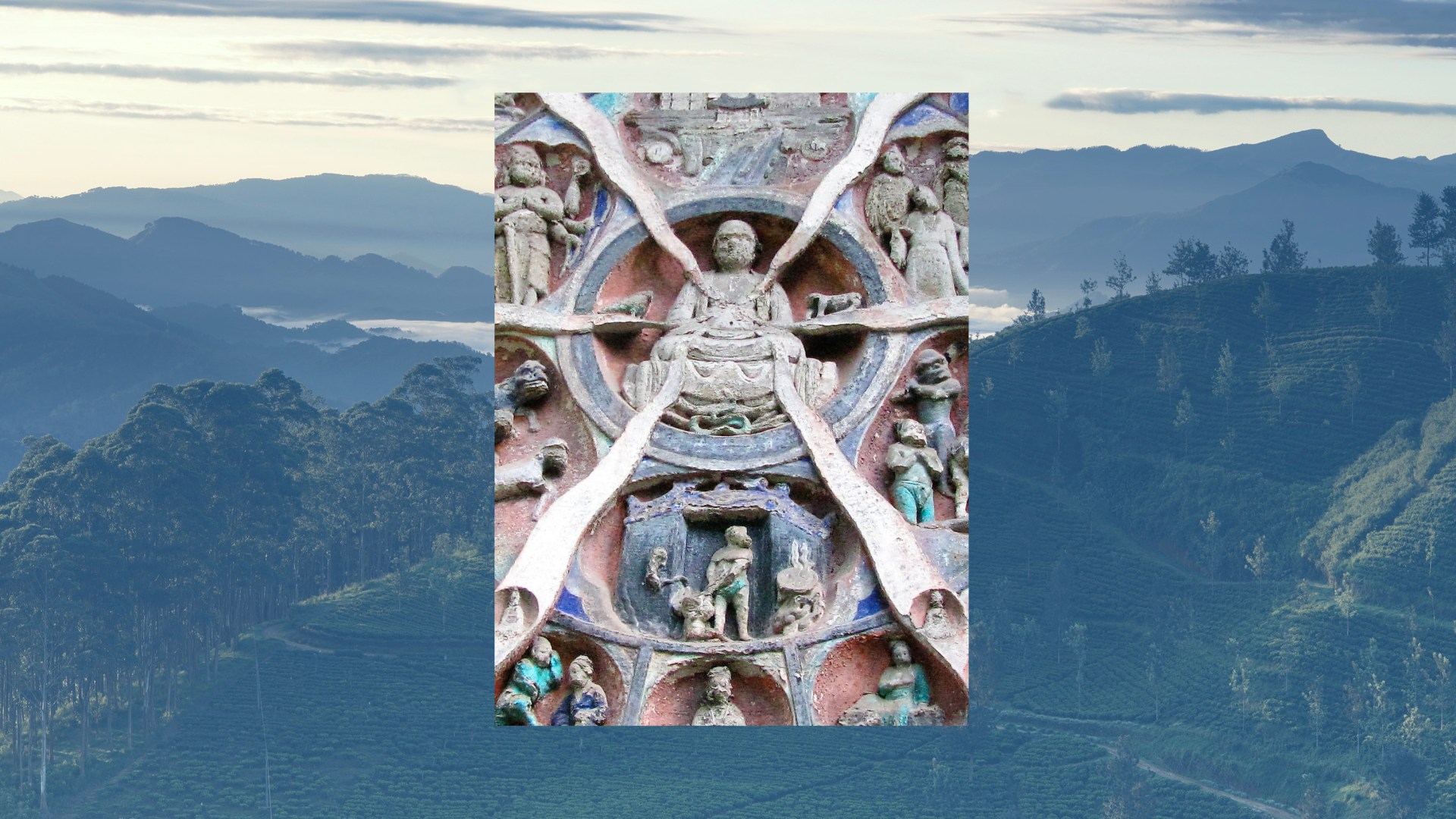

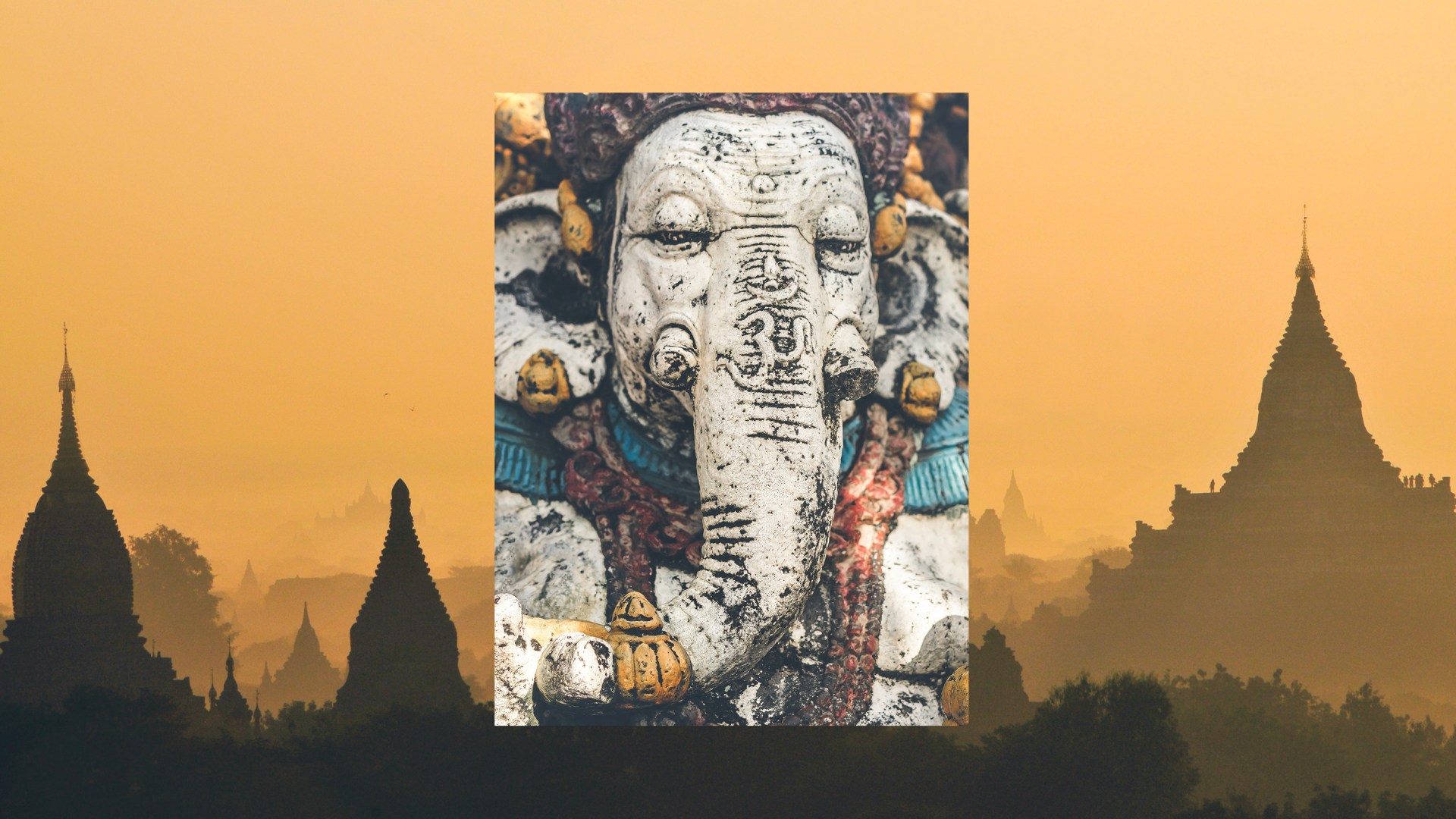

It is akin to what I feel in a great cathedral, looking at its intricate sculpture, metallurgy, and glass—and thinking of the hundreds, or even thousands, of people who spent perhaps their entire lives building such a monument to faith. Their persevering labor is a testimony as much as the beauty it produced.

So too is the labor of Christmas (for, after childhood, labor it mostly is). What I’m inclined to call hassles are joys to others. And if I can catch them from the right angle, in a flash off the brass of sanctuary decorations or the look in a loved one’s eye, they can be joys to me as well.

Bonnie Kristian is the editorial director of ideas and books at Christianity Today.