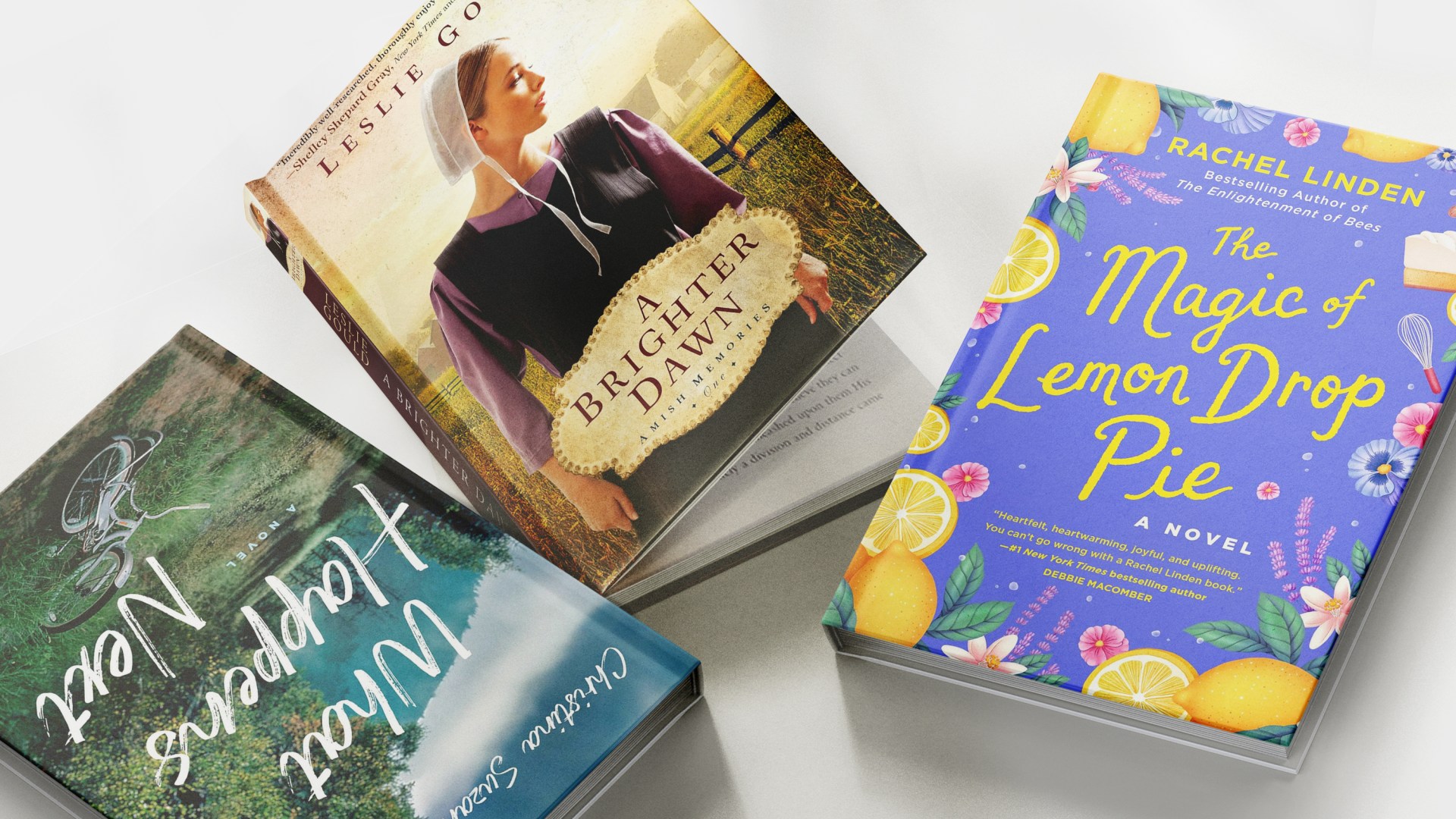

Leslie Gould (Bethany House)

As Ivy Zimmerman, a young Mennonite woman, is grieving the sudden loss of her parents in a mysterious traffic accident, she and her two younger sisters travel to Pennsylvania to spend time with their Amish grandparents. When Ivy learns the story of her great-grandmother, who lived in Germany during the 1930s, she gets a glimpse of what happens when people’s fears lead to deadly compromises. Lingering questions from her parents’ deaths spur Ivy to search for answers, even if they come at a cost. In this challenging story of grief and self-discovery, Gould explores faith, society, and difficult choices.

Christina Suzann Nelson (Bethany House)

Successful podcaster Faith Byrne has made a career of finding inspiration in tragedy, but she’s unable to see anything redeeming in the dissolution of her own marriage and her ex-husband’s impending nuptials. When she’s asked to investigate a notorious cold case—the disappearance of her childhood best friend, Heather—Faith takes advantage of the distraction, embarking on a nostalgic walk through the summer of 1987. Will sifting through dark secrets from the past help her and Heather’s mother find ways to move forward? Nelson will challenge you to consider how events in your own life might be holding you back.

Rachel Linden (Berkley)

Lolly Blanchard has given up on so many dreams to keep her family together and prevent the failure of their Seattle diner. But on her 33rd birthday, as she prepares once more to bake her late mother’s famous pie, Lolly takes stock of her life and sees only regrets. So when her great-aunt presents her with three magic lemon drops that allow her to explore roads not taken, she jumps at the opportunity. This move might backfire, or it could open a pathway to a brighter future. This beautiful and whimsical story echoes It’s a Wonderful Life, albeit with a modern twist.