Confucianism and the Bible agree: Humans are capable of discerning basic moral principles, such as what is good and evil, and we should choose good through our conscience, or general revelation.

Jesus: The Path to Human Flourishing: The Gospel for the Cultural Chinese

Graceworks

142 pages

$11.84

Moreover, Paul acknowledges our struggle and hardship in not doing what we want to do and doing what we don’t want (Rom. 7:15–20) because the Christian worldview believes humans have a fallen nature.

But this biblical view of humanity is harder for those with Confucian values to come to grips with. Their worldview says that humans are basically good and that through education and hard work they should be able to conquer weakness.

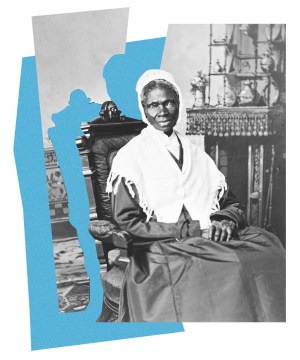

I’Ching Thomas’s book, Jesus: The Path to Human Flourishing, provides valuable insights into three ancient belief systems: Daoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism. It demonstrates how many of God’s truths, which Chinese people have observed and applied from general revelation, can be understood through these ancient Chinese beliefs and acknowledged when sharing the gospel with people of Chinese descent.

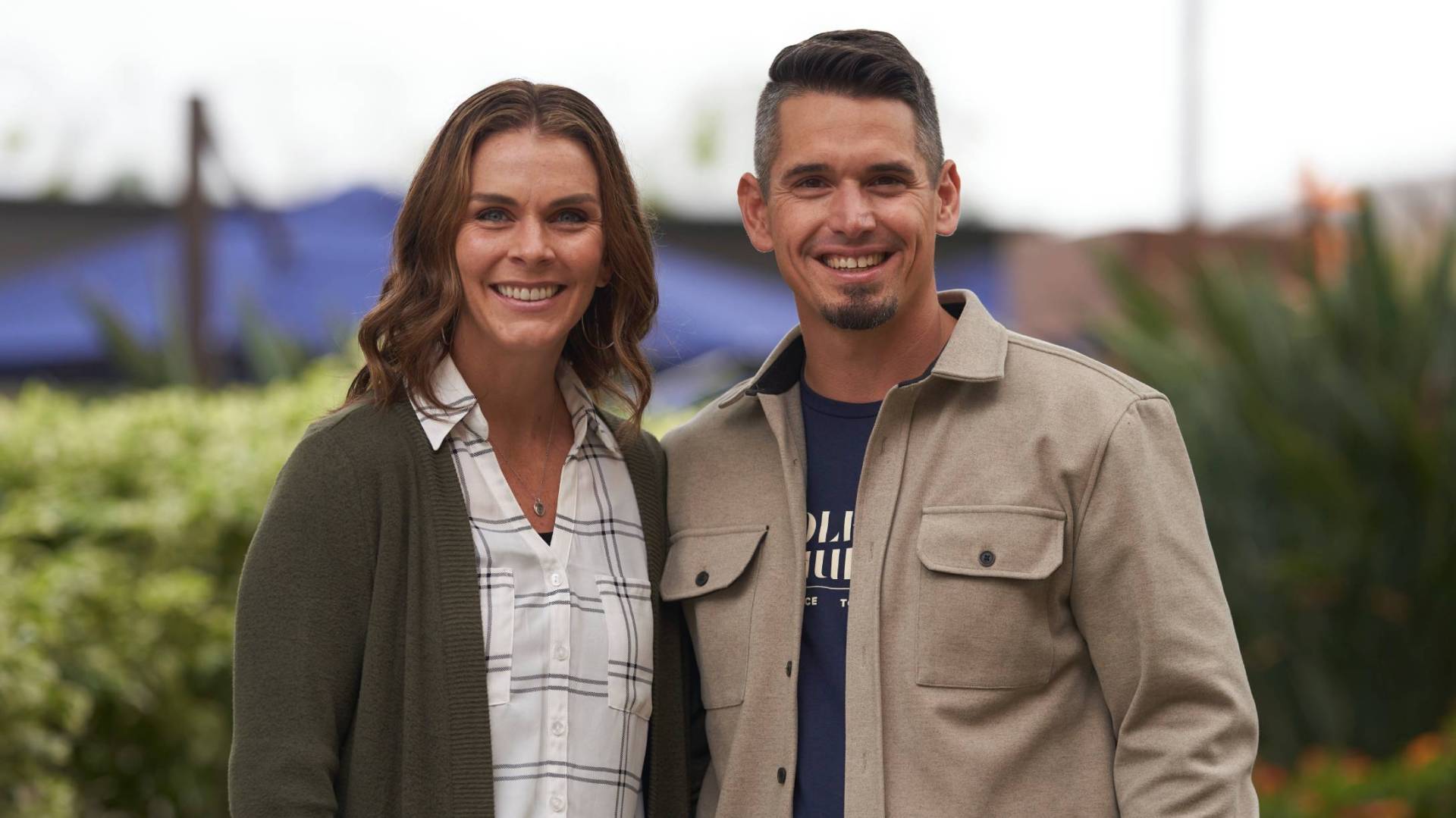

Thomas, a Malaysian Chinese author and speaker who focuses on Christian apologetics in Eastern contexts, hopes to not only share the gospel with the Chinese but also answer the question of why the gospel is necessary for them, as they possess a rich history in their cultural faith traditions.

While charting points of continuity and discontinuity between Christianity and these ancient traditions, Thomas emphasizes that familiarity with this cultural landscape and how it interfaces with Scripture will prove helpful for people who seek to evangelize or develop their faith in this particular context.

Engaging age-old philosophies

Thomas unpacks the Daoist, Buddhist, and Confucian belief systems inherent in Chinese culture that serve as the main contributors to Chinese core values. Her book makes evident that knowing the core beliefs of the Chinese allows us to find greater commonalities between the gospel and their culture, which will enable more conducive and effective evangelistic efforts.

In essence, all three belief systems rely on human effort to attain salvation. In Confucianism, one may develop into a sage-like noble man, or junzi (君子), whose behavior is characterized by virtues like benevolence and righteousness. In Buddhism, one strives to become enlightened and attain nirvana. In Daoism, the goal is to be immortal.

As the book examines these ancient belief systems, it explains how Chinese worldviews have been shaped by each one and how they have contributed to modern-day values that are manifested in daily life.

For instance, Buddhism introduced the concept of reincarnation to the Confucian idea of ancestral veneration. Reincarnation led to the understanding that people could escape hell and take on “good” bodies in their next lives, depending on the quality of their past decisions and actions. Ancestral veneration involves showing respect to deceased ancestors who are thought to “live” on as spirits that can influence what goes on in the real world.

Consequently, when Christians tell their (non-Christian) parents that they cannot perform rites to honor their ancestors, they violate the Confucian virtue of filial piety, upsetting their parents’ beliefs in reincarnation and the afterlife.

Filial piety not only has a bearing on Chinese attitudes toward their ancestors. It also plays out in the Chinese cultural value of respecting and honoring one’s elders. This is most evident during the Lunar New Year, where many Chinese recognize the importance of spending time with relatives and the need to be kind and respectful to them during this festive period, regardless of how frustrating they may be.

Buddhism, Daoism, and Confucianism, Thomas says, were easier to incorporate into the Chinese context compared to more prescriptive beliefs like Christianity. Buddhism is not a canonical religion, while Christianity is canonical as well as exclusive. Confucianism was seen as practical, relating to everyday life and providing society with structure in a time of upheaval. Daoism fit into the traditional Chinese culture of harmony in terms of its dualistic yin and yang beliefs, where yin represents feminine energy and yang represents its counterpart, masculine energy.

Ironically, before these belief systems permeated Chinese thought and worldviews, the Chinese originally believed in an omnipotent, personal God who ruled the world, Thomas writes.

Delving into biblical truth

Along with thoughtful introductions to these belief systems, Thomas also explains how they lead to achieving human flourishing in the Chinese mindset.

Chiefly, she does this by comparing Daoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism’s notions of a good life to the biblical reality of shalom, as defined by Cornelius Plantinga in Not the Way It’s Supposed to Be: A Breviary of Sin:

The webbing together of God, humans, and all creation in justice, fulfillment, and delight is what the Hebrew prophets call shalom. … In the Bible, shalom means universal flourishing, wholeness, and delight—a rich state of affairs in which natural needs are satisfied and natural gifts fruitfully employed, a state of affairs that inspires joyful wonder as its Creator and Savior opens doors and welcomes the creatures in whom he delights. Shalom, in other words, is the way things ought to be.

Responding to common virtues that Chinese people hold, Thomas gives modern-day examples of weaknesses that Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism cannot adequately address or remedy. It is here that she demonstrates how biblical faith answers questions of good and evil, life and death, and ethics.

For example, Confucius believed that humans were flawed because of a bad environment but couldn’t account for what made the environment bad to begin with. This is where his knowledge of the corruption of humanity is correct but incomplete—and where this knowledge can be used to introduce the special revelation of Scripture and the Son of God in the person of Jesus Christ to help us flourish.

Preaching the gospel effectively

Jesus: The Path to Human Flourishing offers a fascinating introduction to basic Chinese belief systems and how they manifest today, even when they may not be followed explicitly. It demonstrates an apologetic approach to convince the Chinese people that their culture may not always conflict with Christian beliefs and that Christianity is not just a “foreign” religion.

Confucianism may no longer be the “state religion” in China, but filial piety and investing in education are strong core values that many Chinese people still have. Philosophical discussions on how to be truly human, or how to be a noble man as Confucius taught, are still very practical in daily life.

Similarly, not many Chinese people today will claim to be Daoist, but a significant number have been strongly influenced by the Daoist arts or hold strong beliefs in the efficacy of Chinese medicine.

Acknowledging these influences as well as the strengths and weaknesses of Chinese culture, Thomas presents several important aspects to keep in mind when sharing the gospel: the deep desire to maintain harmonious relationships and dealing with shame and guilt, self-sufficiency, and practicality.

We can not only address the desire of the Chinese to flourish by highlighting areas of convergence when we share about Christ but also weave their beliefs from general revelation with the shalom of the Bible. Doing so can help them realize that Jesus is the path to the human flourishing they desire.

Thomas’s book is helpful for Christians who evangelize to Chinese people, are looking for an introduction to the history of Chinese belief systems, and are involved in contextualization.

Colleen M. Yim has served as a professor at Jordan Evangelical Theological Seminary and an adjunct at Biola University. She has been involved in cross-cultural work since 1991.

A previous version of this book review was published on ChinaSource.