The names in this story have been changed for the community’s protection

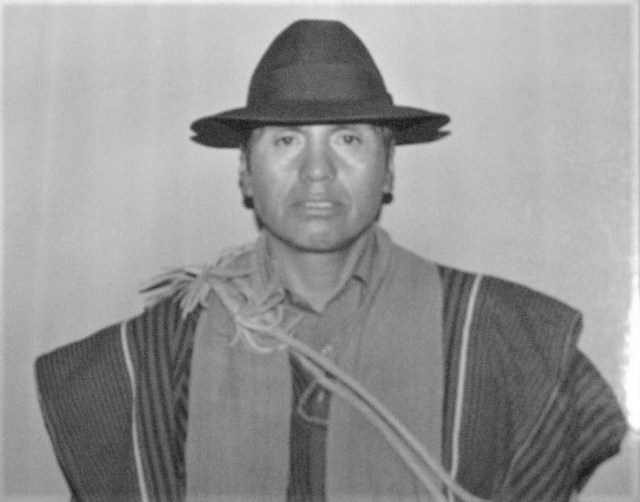

Eusebio Quispe felt out of place and extremely uncomfortable. The Aymara man from the Andean plateau was seated at a banquet along with mayors and council members from across the large Bolivian state of La Paz. Also present was the man who had requested the gathering: Evo Morales, then president of Bolivia. As the South American nation’s first indigenous head of state, Morales inspired the respect and fear of all the native peoples of the high plains, valleys, and jungles.

As the first course of soup was being served, Morales—an Aymara himself—loudly said, half in jest, “Shouldn’t we say a prayer? Aren’t there any Christians in this group?”

A few people tittered, but a mayor pointed directly at Eusebio and said, “There’s your man!”

Now Eusebio felt panic. Even so, he knew what to do. He stood up…

The Aymara have been a significant presence in Bolivia and neighboring Peru for more than a millennium. Today about 2.5 million are spread across the rugged Altiplano, roughly 12,000 feet above sea level.

After the arrival of the first Protestant long-term missionaries at the turn of the 20th century, the Aymara proved receptive to the good news. Quaker missionaries first came in the 1930s and began preaching and forming churches among the Aymara. Eusebio’s branch of the Friends Church currently contains approximately 200 Aymara congregations.

The Friends missionaries recognized decades ago that the Bolivian church was independent and no longer needed a foreign presence. So they left.

The Aymara church continues to be strong—Bolivia now has the second-highest number of Quakers in the Americas, after the United States—but certainly is not without conflicts. Some stem from the nature of being Aymara, which is widely recognized in Bolivian society as a culture of conflict. And some stem from the early impact of the missionaries.

The first American missionaries came to Bolivia out of the vibrant Methodist revival movement in the US and brought with them its doctrines and behavioral standards. Aymara culture favors formality and set rules and procedures, so it was a good fit for this imported faith from the beginning.

While most of these emphases were positive and produced the fruit of a growing church, some proved troublesome. Among these was the teaching that Christians need to separate themselves from the world—a true doctrine theologically that can become false when taken to extremes.

The Aymara are a communal culture, with the community as well as the extended family playing an important role. As each Aymara boy reaches adulthood, he steps into a network of community obligations. These year-long service opportunities come up as an Aymara man progresses through life.

The problem for Aymara Christians is that the obligations include numerous fiestas where ritual acts and drunkenness are expected. A good leader takes his turn supplying the liquor for the gathering. In addition, these times of service require participation in animistic sacrifices to the spirits believed to protect the community.

Because of these dubious aspects, early Protestant teaching demanded that Aymara Christians refuse their community service. This produced severe tension between the church and the community.

Over the years, individuals in evangelical denominations have responded to this tension in different ways. Some believers have completely refused to participate; of these, some have suffered persecution, including loss of property. Many others have announced they are retiring from the church during their years of service; they then perform all the obligations. Some of these return to church after their years concludes, publicly confess, receive forgiveness, and are reinstated into their congregation. Others never return.

And then there are those believers who take the difficult path and manage both to serve their communities and to maintain their Christian testimonies. Eusebio is one of these.

Eusebio is a member of the Ch’ojasivi Friends Church on the Altiplano. As a young man, soon after his conversion in 1975, he moved to La Paz to attend Bible school in hope of becoming a pastor. Upon graduation, he married and moved back to his community, serving a few years as his church’s pastor.

When Eusebio decided to go ahead and fulfill his obligatory time of community responsibility, he asked his congregation to support and pray for him—telling them of his determination not to compromise his beliefs.

During that first year, he discovered he could apply to his new role the administrative skills he had learned in Bible school (e.g., the importance of doing things carefully and in order, following established rules and regulations, adhering to careful financial accounting, and so on). This contrasted with how the tasks had been carried out by previous leaders. Other community leaders noticed this and affirmed him.

His work made a difference, and Eusebio discovered a new vocation in serving his community. He voluntarily continued year after year, fulfilling different roles, climbing the ladder of responsibilities, and eventually leading at the provincial level. As of my interview with him in 2018, he had dedicated more than 30 years to this kind of service.

Since community work demands so much time, Eusebio found it necessary to resign his leadership roles in the church, including as a pastor. However, his church affirmed his calling and continued to be supportive—in contrast to many congregations in other towns. Eusebio has been able to maintain faithful attendance at worship. He started the practice of coming every Sunday at 5 a.m. to pray until the service began. Sometimes others joined him; often he prayed alone.

Eusebio kept his commitment to a strong Christian testimony during his community service—not an easy task given its expectations and pressures. From the beginning, Eusebio let it be known that he was an evangelical Christian and was not wealthy and could not divert much money into sponsoring fiestas; neither would he drink or buy alcohol for them. Once, when it was his turn to sponsor a fiesta, he refused but offered instead to provide a meal for the whole community after the gathering—a more expensive alternative. The result was much appreciated.

Because of Eusebio’s lack of compromise and his commitment to hard work and honesty, his town and the surrounding region respect him and often ask him to pray at the beginning of meetings and events. Tangible contributions he has made to Ch’ojasivi include the constructing of a clinic and a police station, working with a reforestation committee to set up a tree nursery, and serving four years as a high school music teacher.

At the banquet with provincial mayors and the president, after Eusebio prayed over the meal, Morales engaged him in conversation, asking how long the fellow Aymara had been a Christian. Morales then shared that his grandmother used to take him to a Baptist church when he was a boy. Morales especially remembered “I Have Decided to Follow Jesus” as a song that he enjoyed singing as a child. When the waiter served the drinks, Morales asked that they serve a soft drink to Eusebio.

Eusebio’s testimony is not just negation—a refusal to drink alcohol, participate in pagan fiestas, or give offerings to spirits—but a commitment to serve with honesty and integrity, bringing the best of his education and abilities to improve life in his community.

He has a deep concern that the church teach its young people positive ways to fulfill their community responsibilities. Eusebio joins a good number of other Aymara Christian theologians and leaders who are recognizing the holistic nature of the gospel, that along with preaching the word of Jesus and establishing churches, attending to the poor and serving their communities are also part of furthering God’s kingdom on earth.