The loud noise from the opening of an iron door marks Jorge Anguilante’s exit from the Pinero prison every Saturday. He heads home for 24 hours to minister at a small evangelical church he started in a garage in Argentina’s most violent city.

Before he walks through the door, guards remove handcuffs from “Tachuela”—Spanish for “Tack,” as he was known in the criminal world. In silence, they stare at the hit-man-turned-pastor who greets them with a single word: “Blessings.”

The burly, 6-foot-1 man whose tattoos are remnants of another time in his life—back when he says he used to kill—must return by 8 a.m. to a prison cellblock known by inmates as “the church.”

His story, of a convicted murderer embracing an evangelical faith behind bars, is common in the lockups of Argentina’s Santa Fe province and its capital city of Rosario. Many here began peddling drugs as teenagers and got stuck in a spiral of violence that led some to their graves and others to overcrowded prisons divided between two forces: drug lords and preachers.

Over the past 20 years, Argentine prison authorities have encouraged, to one extent or another, the creation of units effectively run by evangelical inmates—sometimes granting them a few extra special privileges, such as more time in fresh air.

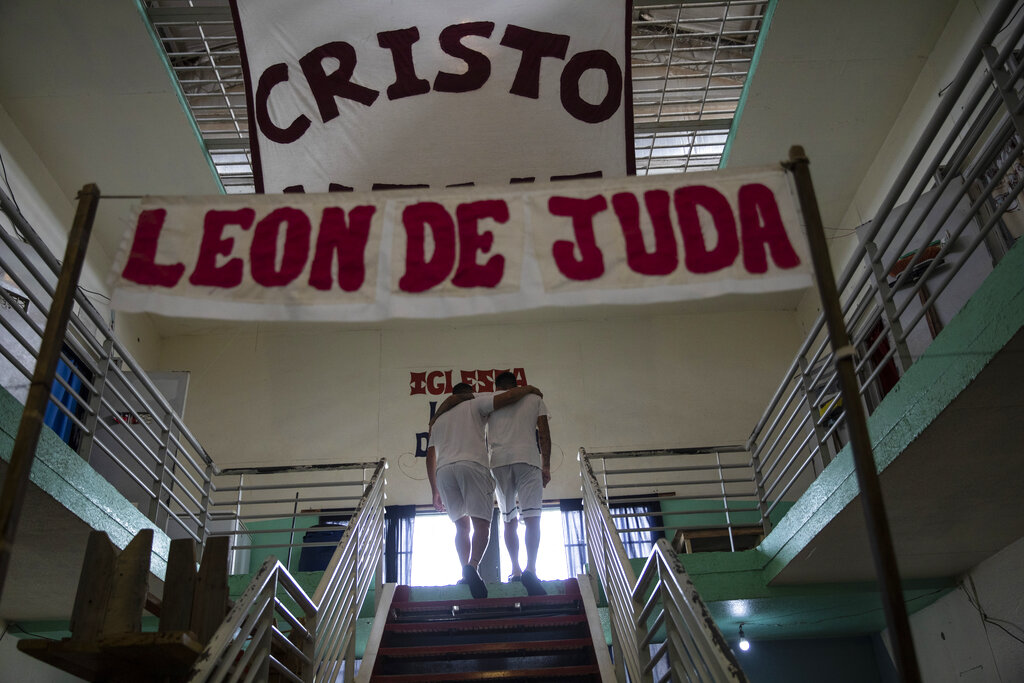

The cellblocks are much like those in the rest of the prison—clean and painted in pastel colors, light blue or green. They have kitchens, televisions and audio equipment—here used for prayer services.

But they are safer and calmer than the regular units.

Violating rules against fighting, smoking, using alcohol or drugs can get an inmate kicked back into the normal prison.

“We bring peace to the prisons. There was never a riot inside the evangelical cellblocks. And that is better for the authorities,” said David Sensini, pastor of Rosario’s Redil de Cristo church.

Access is controlled both by prison officials and by cellblock leaders who function much like pastors—and who are wary of attempts by gangs to infiltrate.

“It has happened many times that an inmate asks to go to the evangelical pavilion to try to take it over. We need to keep permanent control over who enters”, said Eric Gallardo, one of the leaders at the Pinero prison.

Rosario is best known as a major agricultural port, the birthplace of revolutionary leader Ernesto “Che” Guevara and a talent factory for soccer players, including Lionel Messi. But the city of some 1.3 million people also has high levels of poverty and crime. Violence between gangs who seek to control turf and drug markets has helped fill its prisons.

“Eighty percent of the crimes in Rosario are carried out by young hit men who provide services to drug gangs, whose bosses are imprisoned and maintain control of the criminal business from jails,” said Matías Edery, a prosecutor in the Organized Crime Unit in Santa Fe province.

Anguillante says that his life as a contract killer is behind him; God’s word, he says, turned him into “a new man.”

In 2014, he was sentenced to 12 years in prison for killing 24-year-old Jesús Trigo, whom he shot in the face. Anguillante says that face haunts him at night, and he tries to chase the memory away by praying in his small prison cell.

About 40% of Santa Fe province’s roughly 6,900 inmates live in evangelical cellblocks, said Walter Gálvez, Santa Fe’s undersecretary of penitentiary affairs, who is also Pentecostal.

As in other Latin American countries, the spread of evangelical faith in Argentina took root especially in the “most vulnerable sectors, including inmates,” said Verónica Giménez, a researcher at the National Council for Scientific and Technical Research of Argentina.

In Pope Francis’ home country, the Roman Catholic Church is still the dominant religion. But a survey by the council found that the percentage of Argentine Catholics fell from 76.5% to 62.9% between 2008 and 2019 while the share of evangelicals grew from 9% to 15.3%.

“This increase in the faithful took place even more in prisons,” Gálvez said.

Gimenez, the researcher, said that is echoed in other parts of Latin America, such as in Brazil, where the huge Universal Church of the Kingdom of God has 14.000 people working with prisoners.

The growth is remarkable in a country where Catholics had a near-monopoly on prison chapels until a few decades ago.

“There are still Catholic chapels inside prisons but their priests are almost without any work to do,” said Leonardo Andre, head of the prison in Coronda, about 50 miles (80 kilometers) north of Rosario.

Catholic priest Fabian Belay, who runs the Pastoral of Drug Dependence, said that priests are indeed active, but use “different methods” than the cellblock strategy.

“We disagree with the invention of religious cellblocks because they create ghettos inside prisons,” he said. “We bet on integration and not a religious segregation.”

Deacon Raul Valenti, who has been working in the Catholic pastoral for three decades, said, “The evangelicals do their work in the religious cellblocks, while we do them in the other ones, the ones that are called hell.”

He insisted they are not in conflict: “We just have different views. We share, a lot of times, religious activities inside the prison.”

The Puerta del Cielo (“Heaven’s Door”) and Redil de Cristo (“Christ’s Sheepfold”) congregations are among those that exert strong influence in Santa Fe’s prisons. They began to evangelize inmates in the late 1980s and today have more than 120 pastors working inside prisons.

During a recent service at the Redil de Cristo church in Rosario, the Rev. David Sensini asked those who had been imprisoned to identify themselves. About a third in the room raised their hands. They then closed their eyes and lowered their head in prayer.

Víctor Pereyra, who was wearing a black suit and tie, served time at the Pinero prison. Today, he owns a produce shop and also works maintenance jobs.

“I don’t want to go back (to prison). Today I have a family to look after,” he said.

Pop-style hymns blared from loudspeakers while three TV cameras recorded the ceremony for other worshippers watching at home via a YouTube channel.

“No one else is going to jail. Not your children, not your grandchildren,” the pastor shouted to the crowd. “Change is possible!”

Those who refuse to change are soon ousted from the evangelical cellblocks, said Rubén Muñoz, a 54-year-old pastor at Puerta del Cielo who served two years in prison for robbery.

While there are allegations of unrepentant drug bosses bribing their way into the cellblocks, Eduardo Rivello, the congregation’s lead pastor, denied that.

But he acknowledged that several members of the Los Monos gang have lived in those units and said some who come are looking for protection rather than a desire to follow their faith. “We work with everyone,” he said, adding that he also lives under constant threat.

“Drug traffickers want to take over the evangelical units because for them it’s a business,” he said. “From here crimes can be ordered and drugs sold.”

Each evangelical unit at Pinero is run by 10 prisoners who have about 15 assistants for the 190 inmates. “They’re in charge of controlling everything and keeping the peace,” Gallardo said.

“We don’t use knives, but the Bible to take over a cellblock,” said Pentecostal pastor Sergio Prada. Prisoners who want to be allowed in, he said, must comply with rules of conduct, including praying three times a day, giving up all addictions and fighting.

As he led a recent meeting for 90 prisoners at an evangelical unit in Pinero, Prada told them to put their old criminal lives behind.

“That old man has to die!” he shouted, referring to their previous identities.

As he heard these words, Anguilante closed his eyes and cried. He later would say that he already “buried” his old self, the one who murdered and who has been imprisoned for seven years.

“Not everyone can, but you have to try,” he said.

At Penal Unit No. 1 in Coronda, the day in the evangelical units begins and ends with prayer.

One of those praying is Juan Roberto Chávez, who was imprisoned for 16 years in various jails in Argentina and served the last eight years in Coronda. “I hated the world,” he said. “I wanted to destroy it.” He recalled that he lived mostly confined in punishment cells.

“The kids who would arrive would turn into monsters” in prison, Chávez said. He tried and failed to escape. Desperate, he stitched his mouth shut and went on hunger strike.

“Then I got tuberculosis. I was dying,” he said. “I hit rock bottom and I had a revelation.”

On a recent day, Chávez embraced 37-year-old José Pedro Muñoz, who expected to be released on parole after serving an 18-year-sentence.

“Now, you have to be stronger than ever,” Chávez told him.

Muñoz was nervous; the wait for release seems endless. He was a hit man for the Los Monos gang and his body is a testament to Rosario’s drug war. Scars from two shotgun blasts mark his chest. Another from a 9mm bullet crosses his abdomen.

“I set fire to bunkers (armored places where cocaine is sold) with people inside. We did it to drive out the (rival) drug dealers,” he said.

But soon came bad news. A guard arrived and told him that he would remain in prison because other charges had been filed against him.

A few minutes later, he joined other prisoners in prayer.