After the horrors of the Second World War, global attitudes on race began to change as secular and religious leaders called for both civil rights and an end to white rule. While historians usually recount the civil rights movement in the United States with little reference to events in the wider world, religious and secular leaders of the period understood American civil rights as part of part of a larger campaign against global racism.

World Christianity and the Unfinished Task: A Very Short Introduction

Cascade Books

172 pages

$22.37

Attitudes of ethnic superiority were pervasive throughout the Western world, and white, colonial rule was viewed as an expression of the racist worldview. In 1942, a chorus of Protestant leaders began calling for the equality “of other races in our own and other lands.” In 1947, two years after the war ended, the Lutheran theologian Otto Frederick Nolde produced a series of essays arguing for global racial equality, calling for the church to lead the way:

The Christian gospel relates to all men, regardless of race, language or color. … [T]here is no Christian basis to support a fancied intrinsic superiority of any one race. The rights of all peoples of all lands should be recognized and safeguarded. International cooperation is needed to create conditions under which these freedoms may become a reality.

The call for racial equality was part of a worldwide movement that demanded freedom for “all peoples of all lands.” In 1948, the global community adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), a watershed event in the worldwide battle against racism. American Protestant missionaries were highly influential in the language of the UDHR and became vocal proponents for religious freedom as well as global human rights. Attitudes were shifting in the Western world, and missionaries were helping lead the way. W. E. B. Du Bois, who is perhaps best known as an American civil rights activist, is more properly understood as a prophetic voice calling for an end to global racism and white oppression. Though he was an atheist, Du Bois worked alongside Western missionaries in the adoption of the UDHR in 1948 and expressed his belief that Western missionaries had an important role to play in putting an end to global racism.

Yet racism remained an acceptable sin following the Second World War, even among many evangelical Christians. The “problem of the color bar” was a problem among some Christian mission societies during the first half of the 20th century.

During my doctoral studies, I examined the organization that became the century’s largest Protestant mission agency on the African continent. It was in turmoil over how to handle the issue of racial integration in the 1950s. Executives balked at the suggestion by some of its missionaries that it should accept “colored Evangelicals” as full-fledged members of the mission community. Officials in the home office wondered aloud (mostly in closed-door meetings) how they would address the question of equal compensation as well as problems that would arise when the children of Black American missionaries wanted to attend school with the children of their white colleagues. Mission authorities suggested that perhaps they could create separate mission stations that “were staffed entirely by negroes” in Africa.

So some missionaries were working to change racist attitudes abroad, while others were coming to terms with such attitudes in their own ranks. But there is something else I became more aware of as I was toiling away in dusty archives: Those same changing attitudes on global human rights and white rule became a crisis for some missionaries and mission societies even as they tried to remain focused on their primary work of gospel proclamation.

As an example, the mission I became most familiar with was forced to reposition itself due to the rise of nationalism and anti-white sentiment in the 1950s during the Mau Mau Conflict (circa 1952–56). The changes sweeping the African continent created political pressure to “Africanize” all spheres of society (including the church). In the decade that followed Kenyan independence from Great Britain (the process began in about 1958 and independence was announced in 1963), the all-white mission initially resisted pressure from African church leaders for a peaceful handover of its property and power. In spite of assurances otherwise, missionaries feared they would then be pressured to leave the country (thus ending their work).

The mission finally relinquished its authority in the 1970s after African church leaders threatened a hostile takeover, though it was not until 1980 that a complete handover had taken place due to the demands of the African church’s stalwart bishop, who grew weary of what he called the “mission station mentality.” (He was referring to the failure of missionaries to fully “integrate” with the African church.) Foreign control by whites—whether in the nation, the church, or mission societies—was out of step with the times. Even mission organizations that were not fully on board with the changing times brought by decolonization were forced to adjust.

It is important for Western Christians who are engaged in world missions to understand that white supremacy in all its forms has been rejected by the non-Western world. During the latter 20th century, missionaries serving in the non-Western world were keenly aware of this global mood. Throughout the African continent during the second half of the 20th century, colonies rebelled against their Western masters, buoyed by the fight for human freedom and the end of global racism. As former colonies became independent, Western missionaries from various denominations, Catholic and Protestant, were forced to relinquish ecclesiastical authority.

The transitions “from mission to church” (referred to as “devolution”) in various denominations were often tense and uneven. Progressive voices within mission circles called for devolution as soon as possible. Max Warren (1904–77), who served as the vicar of Holy Trinity, Cambridge from 1936 to 1942, and the general secretary of the Church Missionary Society from 1942 to 1963, was especially persuasive in convincing the global mission community to adjust to the changes sweeping the world during decolonization.

In most cases, missionaries and mission societies responded with alacrity, preparing local leaders for positions of authority as quickly as possible, often out of concern that they would be forced to leave the country by new government regimes that might be hostile to Western workers (as in China in 1949 and the Belgian Congo in 1960).

In newly independent nations where mission societies were allowed to continue working, missionaries sometimes felt compelled to relinquish control of the church, fearing that they might be perceived as antigovernment or even racist. Conditions in South Africa were even more complex, with church and state intertwined in private and public spheres, and racial tensions continuing well past the end of apartheid (1994) up to the present day. In China and India, most Western missionaries had already been pressured to return home by 1950 due to anti-Western sentiment, and mission societies had no choice but to hand over the leadership of the church to indigenous leaders. In Latin America, while nations had experienced political freedom more than a century earlier, frustrations mounted in the middle of the 20th century over the elitism that was displayed by church hierarchy.

Christian leaders, both Catholic and Protestant, expressed solidarity with the poor and oppressed through the espousal of liberation theology in the 1950s to the 1990s. This form of theology, drawing heavily on the Exodus motif, argued that God is on a mission to set his people free, both spiritually and politically. The rhetoric of liberation theology was often anti-Western, and some of the criticisms of liberation theologians were directed toward Western missionaries who were viewed as neocolonialists. From the 1940s through the 1990s, Western missions societies were pressured to adjust to the rapidly changing world around them. “White rule” in all its forms was being rejected in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

I learned about the growth of Christianity in the non-Western world during my sabbatical in Kenya in 2006, and I also learned a lot about the attitudes of non-Western Christians toward Western missionaries. A research project I undertook while in Kenya showed that Africans not only resented the legacy of Western control and racism (this did not surprise me), but they also believed that mission societies had displayed attitudes of cultural and racial superiority. Many Africans believed that the reluctance of Western missionaries to provide adequate ministerial preparation for local leaders was an expression of cultural and racial superiority.

While I was lecturing in the church history department at the Nairobi Evangelical School of Theology that year, a pastor from Ukambani (near Machakos, Kenya) came by my cottage one evening to deliver a copy of Joe de Graft’s literary masterpiece Muntu. The African play was performed in 1975 at the World Council of Churches gathering in Nairobi and is now considered a classic in African literature.

In the play, the Waterpeople arrive while the sons and daughters of Africa are fighting among themselves over how to govern their own affairs. The “First Water-man” is a Christian missionary who has come to Africa to make converts; the second is a trader who sets up a shop for buying and selling; the third is a white settler in search of land; the fourth is a colonial administrator with plans to build a railway for exporting gold.

The Waterpeople were brandishing muskets, and even the missionary proved to be an excellent marksman. The African pastor who handed me the play explained that de Graft’s work would help me understand the mindset of many Africans, especially those who were university educated. African Christians, I was to learn, remember that the Western missionary arrived along with the settler, the trader, and the colonial administrator—often on the same ships. More discerning Christians, he informed me, understood that the missionary had different aims. However, he continued, it was important for me to understand that a new generation of African leaders had emerged who would not abide anything that resembled Western superiority. The end of white rule in non-Western nations, he wanted me to understand, also meant the end of any hint of white rule in the African church.

Christians in Africa, Asia, and Latin America want (and deserve) to work with the church in the Western world as coequals in the gospel for the cause of global missions. Church leaders in the non-Western world are keenly aware of the history of subjugation that they and their forefathers have endured. They do not want to be ignored, bypassed, looked down on, or patronized by the Western church—arriving in their country to carry out their work independently as though no African, Asian, or Latin American church actually exists. They want the Western church to serve with them in common witness. They also want Western church leaders to acknowledge them, respect them, and listen to them. They want Western Christians to first understand their needs and then come and serve alongside them.

It is easy to mistake the hospitality offered by the people of the non-Western world to Western visitors for willing subservience. But it is critical to understand that attitudes toward North Americans and Europeans have changed during the 20th century and that even hospitable hosts are aware of the long history of cultural and racial superiority.

Bishop Oscar Muriu is an influential Christian leader on the African continent who has also become a personal friend. I have been the recipient of his kind hospitality on many occasions, and he has been a guest in my home on more than one occasion. We have had many frank discussions over good meals. In a recent exchange, I was soliciting his counsel on a matter related to missions, and he opined (again) about “all the white people from the West…dreaming [about missions] in the 2/3 world.”

Our non-Western brethren want us to be engaged in mission, but they don’t want to be ignored, especially when we are planning mission initiatives in their own backyard! As the Kenyan activist and photojournalist Boniface Mwangi put it in a 2015 op-ed published in the The New York Times: “If you want to come and help me, first ask me what I want…then we can work together.” It is not the “The White Man’s Burden” to save the world; it is the responsibility of the whole church to take the whole gospel to the whole world.

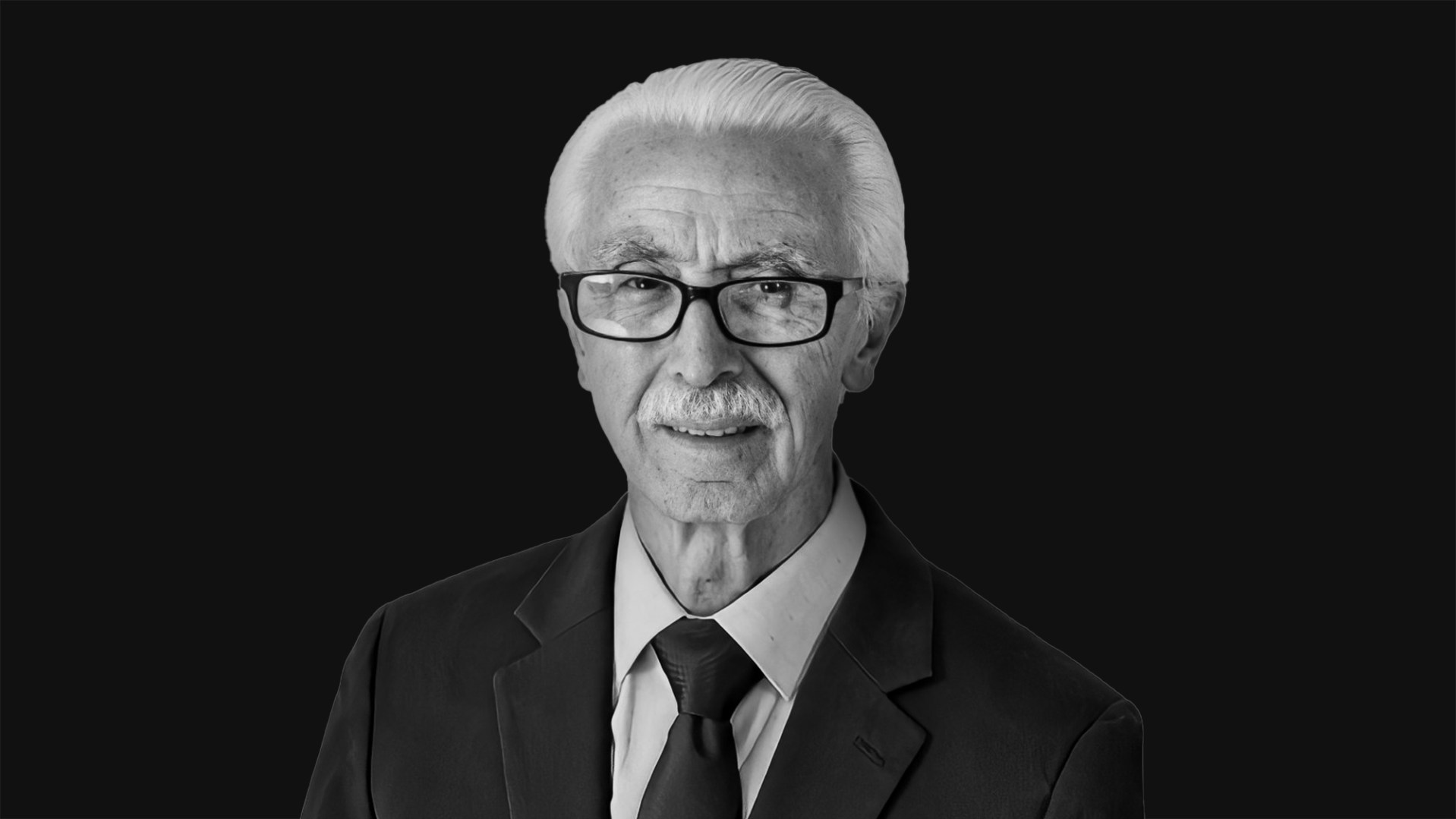

Adapted from World Christianity and the Unfinished Task, by F. Lionel Young III. Used by permission of Wipf and Stock Publishers, www.wipfandstock.com.