One of the great marvels of Scripture is the way minor characters embody an entire narrative. The Bible is full of obscure individuals about whom we know little besides their names. Yet many of them, instead of shuffling on and off the stage to advance the story (like they would in Homer or Shakespeare), become living examples of the story itself.

The most dramatic examples, for my money, occur in the crucifixion story. Think, for instance, of Simon of Cyrene carrying the cross, as Christ told his disciples they would (Mark 15:21). Or the criminal crucified next to Jesus who receives forgiveness at the last minute, becoming the archetypal deathbed conversion (Luke 23:39–43). Or the Roman centurion who supervises the execution and then exclaims, on behalf of billions of Gentiles in the centuries to come, “Surely this man was the Son of God!” (Mark 15:39).

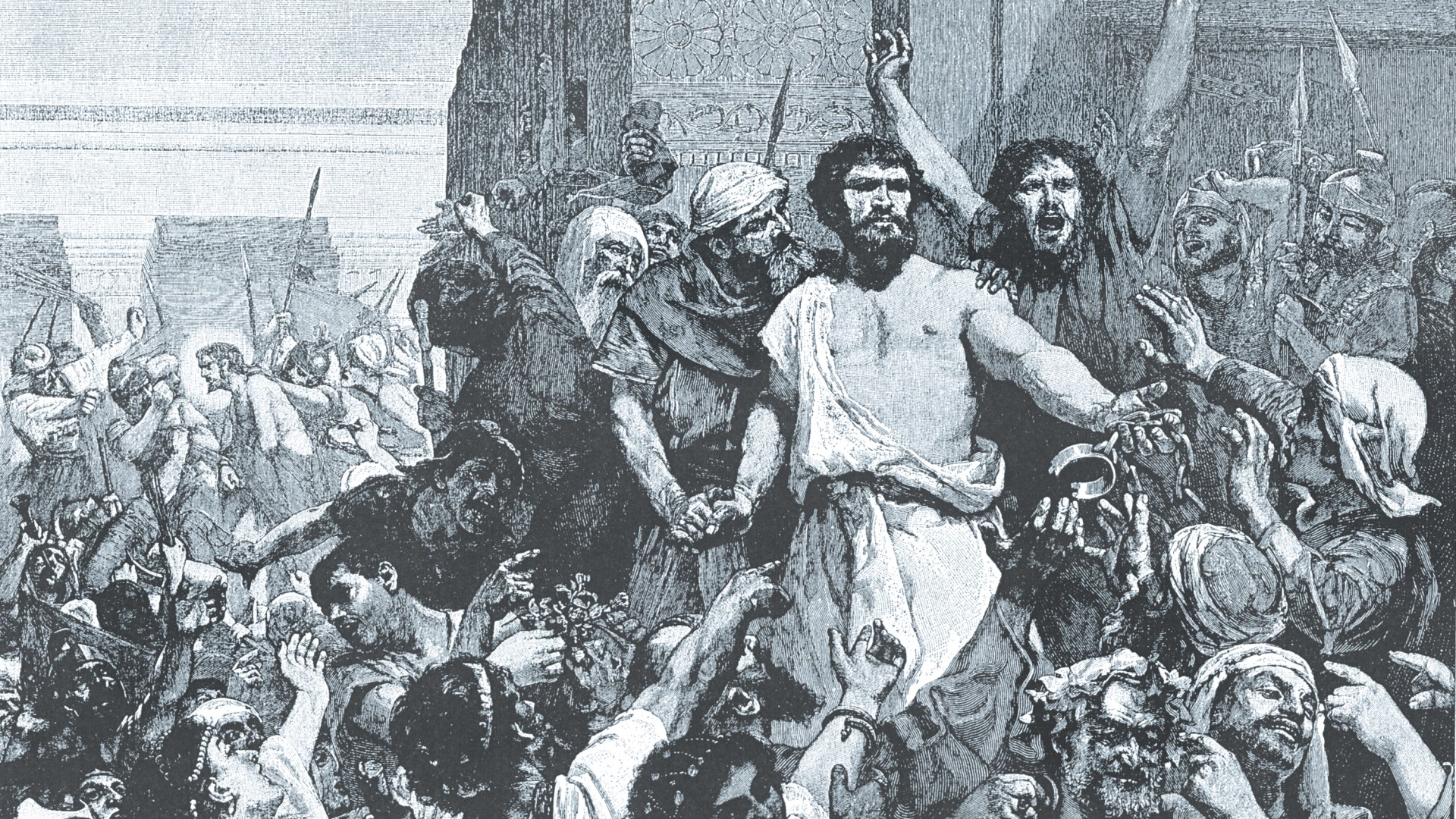

But my favorite example is Barabbas. At one level, his is a simple story of exchange. Barabbas is due to die for his sins, and he deserves to. Yet without doing anything to merit mercy, he discovers that Jesus is going to die instead. Having awoken on Friday morning expecting nothing but a slow, horrible death, by evening he is home with his family to celebrate the Sabbath. We are clearly intended to see ourselves in this man: destined for death but finding freedom and life through the death of another.

If we reflect for a moment, it becomes clear this is not merely an exchange, but a substitution. Jesus doesn’t just die instead of Barabbas; he dies in his place as his substitute, his representative. We know this because—and this is often missed—Barabbas and Jesus stand accused of the same crime: sedition, insurrection, treason. Barabbas is a revolutionary who has directly challenged Roman rule (Luke 23:18–19). And from a Roman point of view, Jesus’ claim to be king of the Jews poses a threat to Caesar. Few examples of substitutionary atonement in Scripture are clearer than Jesus, the innocent man, taking the penalty so that none remains for the guilty Barabbas.

There is also an Exodus dimension here. The Gospels point out that freeing prisoners is a Passover custom. In other words, it happens in honor of the night when Pharaoh’s firstborn son died so that God’s firstborn son (Israel) could be released. But the Gospels raise a subtle question: Which of these two accused men is really God’s firstborn son? The one whose name, Bar-abbas, means “son of the father”? Or the one claiming to be the Son of God? And is God’s Son playing the part of Israel, escaping to freedom—or that of the Passover lamb, shedding his blood to liberate others?

Another layer to the story is the question of how Israel should respond to Roman rule. Barabbas represents the way of war, strength, and violent insurrection. Jesus represents the way of peace, innocence, and sacrifice. When Pilate asks the crowd for their preference, this is the point at issue. And Jerusalem chooses the way of violence—“No, not him! Give us Barabbas!” (John 18:40)—as Jesus tearfully predicted it would (Luke 19:41–44). But the Prince of Peace will enjoy vindication—not least through the mouths of Roman soldiers, the men of violence par excellence (Matt. 27:54; Luke 23:47).

For a final lens on the Barabbas story, consider the Day of Atonement. On this crucial day in the Jewish year, the high priest would cast lots over two goats. One became the sacrificial goat, whose blood was spilled. The other became the scapegoat, who was released from the camp into the wilderness. The parallels with the Barabbas story are fascinating—one dies while the other is released—not least because it was the chief priests who wanted Barabbas released and Jesus killed (Mark 15:11). When, like a priest scrutinizing a sacrificial animal, Pilate explains that he has “examined” Jesus and found him faultless (Luke 23:14), the Levitical echoes grow louder still.

Barabbas was a revolutionary and a murderer. He has no right to be remembered at all, let alone held up as an example of divine grace. But that is the whole point. Neither do I, and Christ died for me anyway. And through his substitution, I become a Bar-abbas myself: a son of the Father.

Andrew Wilson is teaching pastor at King’s Church London and the author of God of All Things. Follow him on Twitter @AJWTheology.