The Supreme Court is reviving a lawsuit brought by a Georgia college student who sued school officials after being prevented from distributing Christian literature on campus.

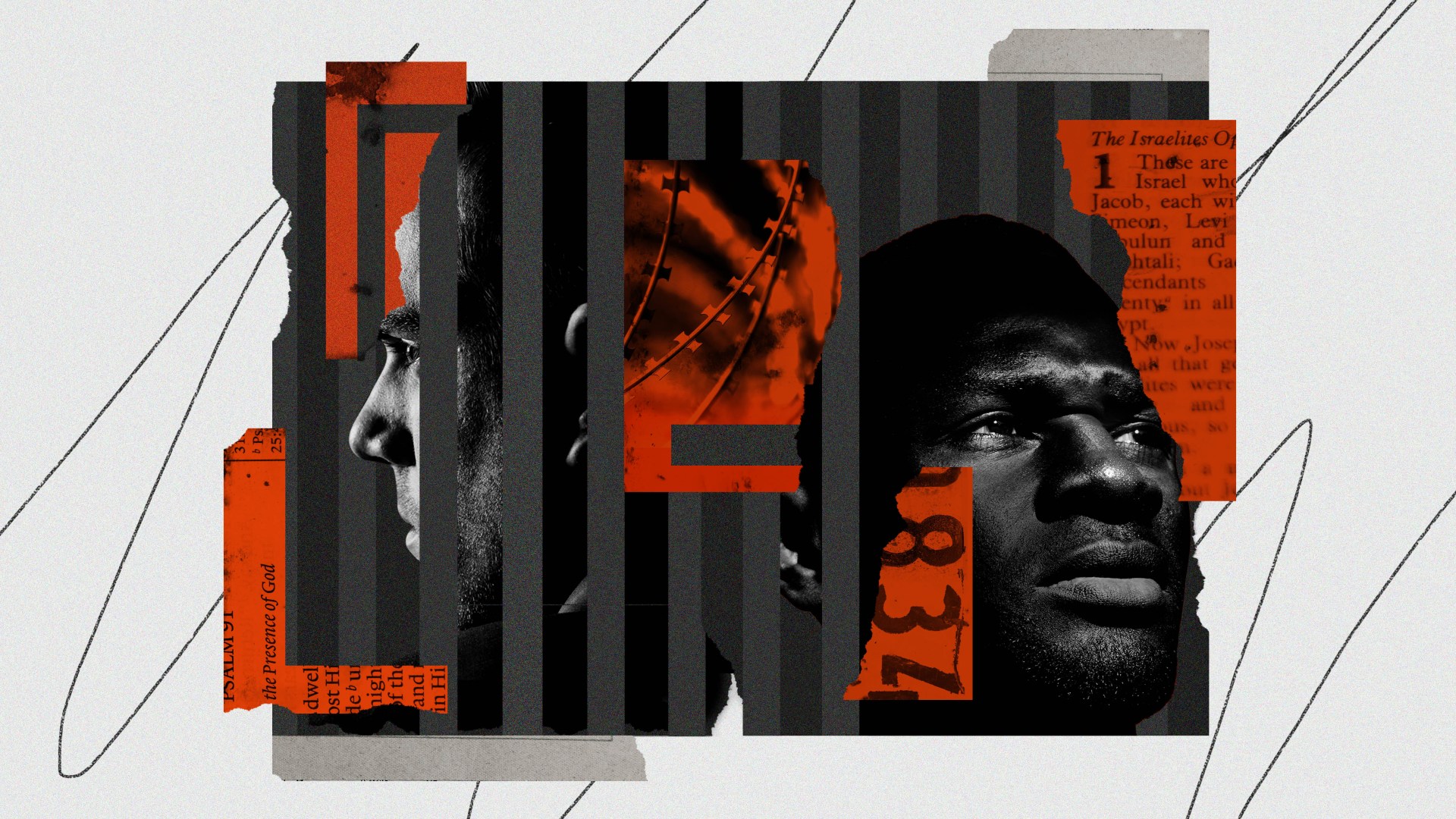

The high court sided 8–1 with the student, Chike Uzuegbunam, and against Georgia Gwinnett College. Uzuegbunam, a Nigerian who converted to Christianity in college, has since graduated. The public school in Lawrenceville, Georgia, has since changed its policies. Lower courts said the case was moot, but the Supreme Court disagreed.

Groups across the political spectrum—from the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty and the Foundation for Moral Law to the American Civil Liberties Union and the American Humanist Association—have said that the case is important to ensuring that people whose constitutional rights were violated can continue their cases even when governments reverse the policies they were challenging.

At issue was whether Uzuegbunam’s case could continue because he was only seeking so-called nominal damages of $1.

“This case asks whether an award of nominal damages by itself can redress a past injury. We hold that it can,” Justice Clarence Thomas wrote for a majority of the court.

Writing only for himself, Chief Justice John Roberts disagreed. Roberts argued that the case brought by Uzuegbunam and another student, Joseph Bradford, is moot since the two are no longer students at the college, the restrictions no longer exist and they “have not alleged actual damages.”

Writing about the symbolic dollar they are seeking, Roberts said that: “If nominal damages can preserve a live controversy, then federal courts will be required to give advisory opinions whenever a plaintiff tacks on a request for a dollar.” He accused his colleagues of “turning judges into advice columnists.”

It appears to be the first time in his more than 15 years on the court that the chief justice has filed a solo dissent in an argued case. That’s according to Adam Feldman, the creator of the Empirical SCOTUS blog, which tracks a variety of data about the court.

Uzuegbunam’s lawyer, Kristen Waggoner of Alliance Defending Freedom, cheered the ruling.

“The Supreme Court has rightly affirmed that government officials should be held accountable for the injuries they cause. When public officials violate constitutional rights, it causes serious harm to the victims,” she said in a statement. “We are pleased that the Supreme Court weighed in on the side of justice for those victims.”

Georgia Gwinnett College did not immediately respond to a request for comment Monday.

In January, during arguments in the case which the justices heard by phone because of the coronavirus pandemic, Justice Brett Kavanaugh said it was his “strong suspicion” that the dispute has continued because the issue of nominal damages is important to determining who pays Uzuegbunam’s attorneys fees.

Georgia Gwinnett College for years had a restrictive policy that limited where students could make speeches and distribute written materials to two “free speech expression areas.” Students had to get permission to demonstrate, march or pass out leaflets in other areas.

In 2016, Uzuegbunam was distributing Christian pamphlets and talking to students on campus when a security guard told him he’d need to make a reservation and distribute the literature in one of the college’s two speech zones. But when Uzuegbunam did, he was approached again and told that there had been complaints and that he’d need to stop.

Uzuegbunam sued and the college changed its policy in 2017. Students can now generally demonstrate or distribute literature anywhere and at any time on campus without having to first obtain a permit. The college has said it won’t go back to its old policy.