The earth is cracked in paraiba state. The sun burns everything in this remote part of Brazil’s Northeast. Despite the many small farms, there is little food. Most people eat once a day, and one person in three is illiterate. The region is the poorest part of the world’s most Roman Catholic nation.

But in the tiny town of Itaporanga, the Missionary Baptist Church is holding a fundraiser. A tithe, for most of the church’s 25 members, is less than an American dime. Gildário Nevez, the 32-year-old pastor of Missionary Baptist, was born in the village and has never gone to school. “Jesus taught me how to read,” Nevez says. “He is sovereign!”

Nevez hosts a radio broadcast on a local station that church members hope to keep on the air with the funds they raise. Radio is the only way church members can regularly hear Nevez preach. Otherwise, many members must walk 20 miles to church in town.

With no cash income, Maria de Lourdes has no tithe to give. Her husband is unemployed. The couple has two young children and rarely enough to eat. She decided to give her rooster, the only thing she owns, as her tithe. But she says, “God has given us so much more.”

Training and gaining

In a geographical area four times larger than Texas, evangelicals are scattered among the Northeast’s 45 million residents. The region has the fewest number of evangelicals among Brazil’s 173 million people. Researchers report that 10 percent of the people in the Northeast are evangelical, compared to a national figure of 16 percent. Yet evangelicals are growing most quickly in the Northeast, at 8.67 percent per year in the last few decades. The Brazilian evangelical movement, largely charismatic, has grown sevenfold during the past 30 years.

Economically, though, the Northeast’s defining characteristic is poverty: 5.4 million people in the region’s nine states live on $1 a day or less. Most people here survive on subsistence farming and animal husbandry. Others rely on money from relatives working in cities. Brazil’s government has met limited success in improving the standard of living in the million-square-mile region, in part because of chronic drought and the region’s poor soil.

Educational organizations such as the Leadership Training Center (Centro para Treinamento de LídereS, CTLS) have helped new evangelical churches open and grow. The center is an arm of the Protestant Brazilian missions agency, juvep (Juventude Evangélica Paraibana), based in João Pessoa, the capital of Paraiba.

In the last five years, 150 students have graduated from the two-year CTLS program.

Students attend one class every other Saturday at central locations. “Our goal is to prepare local leaders to preach the gospel in their own context,” says Pedro Silva, director of CTLS. “We have students who travel 145 miles in the back of a truck in order to study.”

The curriculum aims to prepare lay ministers across Protestant denominations to preach and plant churches. It includes courses in ecclesiology, missions, and theology. Portuguese language classes are available for those students who need them. The cost of this training in the major cities is $60 a month. In poor villages such as Itaporanga, the cost is just 25 Brazilian reals ($6.75) per month. Still, most students cannot afford even that. CTLS provides scholarships to a few students. Large churches in the region support others. In a few cases, citizens pool their resources to help sponsor students.

Lack of trained clergy is a longstanding problem in Brazil for nearly all Christian groups. It has been a chronic problem among Roman Catholics, in part because Catholics have lost ground to Protestants (see “Brazil’s Christian roots,” p. 81). The Catholic share of the national population fell by 10 percent in the 1990s, while evangelicals grew by 70 percent. There are 126 million Catholics and 27 million evangelicals in Brazil, according to recent research. The requirements of CTLS training are less burdensome than training for the Catholic priesthood, which in Brazil includes five years of schooling away from home and a lifelong commitment to celibacy.

Living in adversity

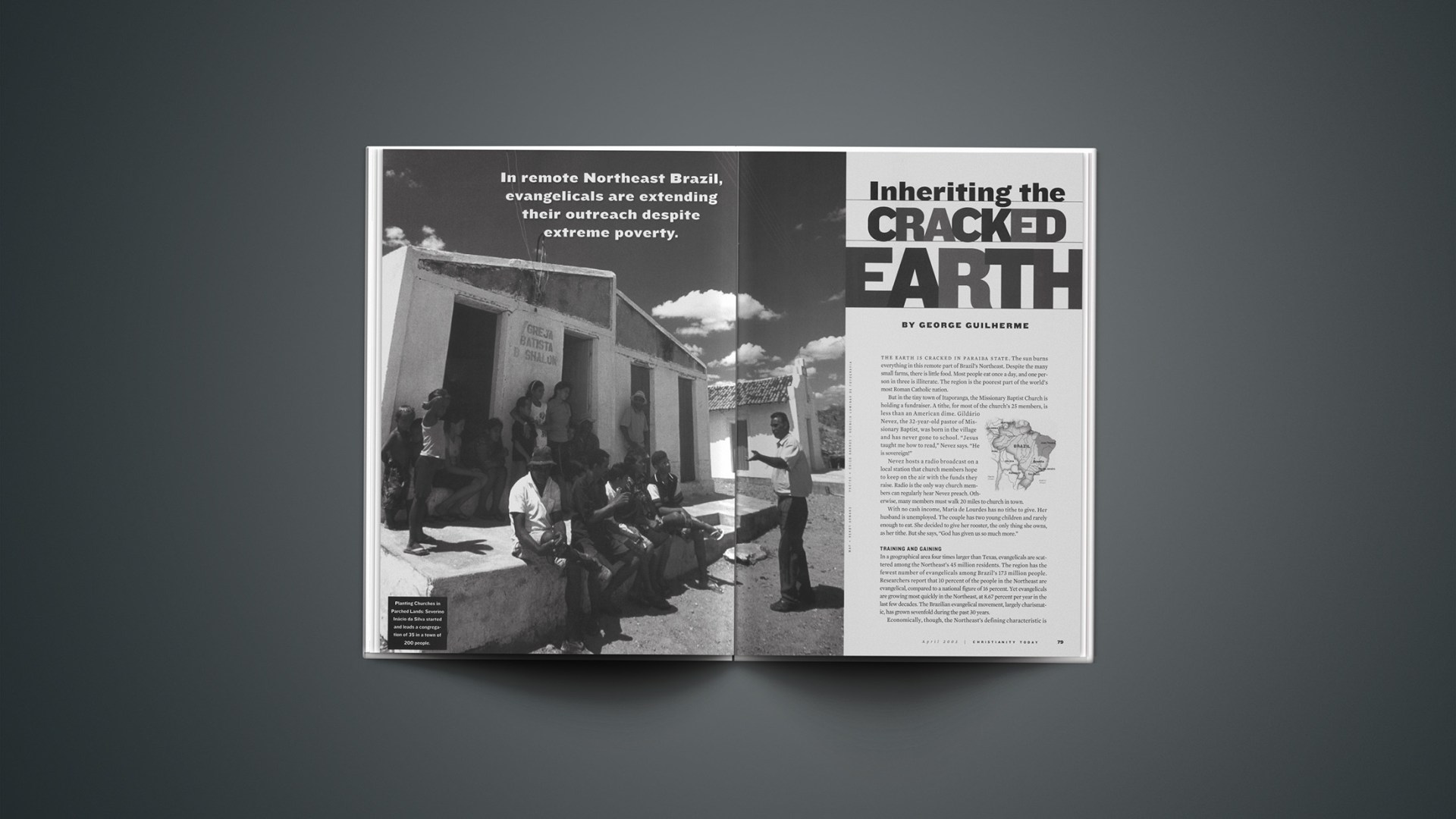

Severino Inácio da Silva was born on Sítio Cipó, a small farming community of 200 in the city of Santana de Mangueira. Four years ago, he was the first person to become a born-again believer in Sítio Cipó. Four months later, he entered the CTLS program and started a congregation. After three years, 35 people in Sítio Cipó regularly attend worship services. Inácio’s Beth Shalom Baptist Church recently moved into a building beside a 100-year-old Catholic chapel. “The [Catholic] priest comes here once a year, while here at our church, people are accepting the Lord,” Inácio says.

His experience shows that investing in local leadership works. “These people know how to live in adversity,” Silva says. “They never give up. That’s why we have had great results.”

As evangelicals in the Northeast have expanded their ministry beyond evangelism to social outreach, they have won new respect from Catholics. As a result, longstanding tensions between Catholic and Protestant neighbors are easing. Discrimination and harassment of evangelicals, common in the 1950s, is largely a thing of the past. Christian leaders have condemned extreme religious intolerance coming from either side. Caio Fabio, a leading evangelical, rebuked a Pentecostal pastor in 1995 when he destroyed an image of the Virgen Aparecida, a revered Marian effigy, on live television.

Recent research shows that 80 percent of people in the Northeast respect and admire evangelicals for their religious message. “Our biggest challenge is not to fight Catholicism, but poverty,” Silva says.

A recent research project sponsored by Diaconia (an organization that brings together 11 evangelical denominations) found that 60 percent of 443 churches in Brazil’s Northeast are engaged in some kind of social work. For example, Seventh-day Adventists are heavily involved in combating HIV/AIDS in the interior of Bahia state. Sérgio Andrade, coordinator of Diaconia’s social programs, says this effort is just a beginning. “It’s an advancement, but the problem is that the works are isolated,” Andrade says. “The various churches are not working together.”

Another rooster

While the average annual income in relatively prosperous southern Brazil is about $5,000, in the Northeast it is only $1,200. The United Nations reports that the South has a standard of living comparable to that of Belgium, but the Northeast standard of living is closer to that of India. Because of the Northeast’s poverty, help must come from wealthier churches elsewhere, according to Serguem Silva, national director of World Vision Brazil.

“The churches in the major centers have a big responsibility for those in the interior,” Serguem Silva says. “We are just a bridge.”

Bridge-building involves developing programs to fight childhood malnutrition and other social ills. Because of the ministry of CTLS, World Vision is planning to implement two programs in Itaporanga: one to feed 2,000 children and another to build cisterns for local residents.

When Pedro Silva heard about the rooster tithe by Maria de Lourdes, he praised her in e-mails sent to large churches in Brazil. One congregation in the Southeast sent her $235. Her family now has another rooster, as well as a bicycle, a refrigerator, and a small television in its spartan house.

The new president of Brazil, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, has recognized the social work done through the growing evangelical community. He is calling on evangelicals, who supported him heavily in the fall election, to step up the pace of social reform (CT, Dec. 9, 2002, p. 22).

“I challenge the churches to participate in national reconstruction,” da Silva said. “I lean on the evangelicals to help me change Brazil.” This challenge includes an invitation to fight hunger. “This is the mission of my life,” the new president said. His first official act was to start a Zero Hunger program. Bishop Dom Fernando Saborido, director of the Catholic National Brazilian Bishops Conference in the Northeast, believes evangelicals are up to the challenge.

“In the past, the concern was only the Word, but now evangelicals care about the body, too,” Saborido says. “They realized there’s no competition when the subject is fighting poverty.”

Sebastião Eugênio, called Brother Tião by his friends, has firsthand experience with poverty. He lives 40 miles from Itaporanga in the village of Olho Dágua. Thirty-five people regularly gather at the only evangelical church in the area. As the leader of this small congregation, Eugênio is learning how to read with his Bible. He has eight children and receives no salary from the church, which is unable to pay its bills. But he is not worried.

“God is in control,” Eugênio says. “He has never left me helpless. He wants me here talking to those who are like me.”

George Guilherme is a senior reporter for Globo TV, a major television network in Latin America, in Recife. He is also a correspondent for Eclesia magazine.

Copyright © 2003 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere

Also appearing on our site today:

Brazil’s Christian Roots | Since the 1600s, the number of protestants has risen to more than 27 million.

Previous CT articles on Brazil include:

Evangelicals Grow as Political Force in Brazil | New interest in public policy fuels election wins. (Nov. 15, 2002)

Jesus for President | A Brazilian election judge sues Jesus for early campaigning. (July 22, 2002)

Brazil’s Surging Spirituality | Churches of all stripes have been growing for decades, as have the controversies and challenges facing evangelicals. (Dec. 21, 2000)

Pie-in-the-Sky Now | Two scholars argue that Pentecostalism, especially in Brazil, is not so otherworldly as many think. (Nov. 27, 2000)