Unlike its tense annual meetings over the last few years, when partisan allegiances shook up the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC), leaders at this week’s gathering offered broad encouragement to transcend political divides, while the messengers rallied together to condemn sexual abuse.

The abuse issue has offered Southern Baptists a common enemy, in contrast to some of the infighting that has surrounded President Donald Trump’s election and presidency. Last year, the messengers debated over the decision to invite Vice President Mike Pence to speak, and the year before, controversy mounted over Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission president (ERLC) Russell Moore’s position against Trump during the 2016 campaign.

The 2019 SBC annual meeting was themed “Gospel Above All,” a line borrowed from president J. D. Greear about keeping secondary issues—including politics—from dividing them. “Political affiliations have a way of obscuring the gospel,” he told the 8,000-person crowd at an arena in downtown Birmingham, Alabama, during his presidential address. “You’re going to have to make a choice this election whether the gospel above all is a priority at your church or politics is.”

Some Southern Baptists viewed Greear’s approach, whether they liked it or not, as a sign of a political shift for the conservative denomination. (The SBC has hosted at its annual meeting the president and/or vice president from the past three Republican administrations, but not the Democratic ones. A motion came up last year to bar elected officials from speaking other than local leaders in the host city.)

It’s a “new day in the SBC when a president makes a statement distancing the SBC from the Republican Party,” said Dwight McKissic, a Texas pastor who has urged messengers to officially reject white supremacy, the alt-right, and confederate flags. Leaders like Larry Felkins, a regional association director and seminary trustee, saw the remarks as “Trump bashing.”

The question remains whether the cry for “Gospel Above All” will continue to unite the SBC in 2020, or if the upcoming presidential election will reintroduce more tensions. The political tenor among Southern Baptists this week, during the largest gathering of America’s largest Protestant denomination, leads into a bigger question: Have evangelicals’ approach to politics really changed since 2016?

White evangelical Protestants, the most-talked-about demographic surrounding Trump’s rise, continue to lean Republican and favor President Trump heading into the next election. Yet, there are also indicators that faithful evangelical voters are thinking about their political engagement differently, especially when compared to fellow Republicans and fellow Trump supporters.

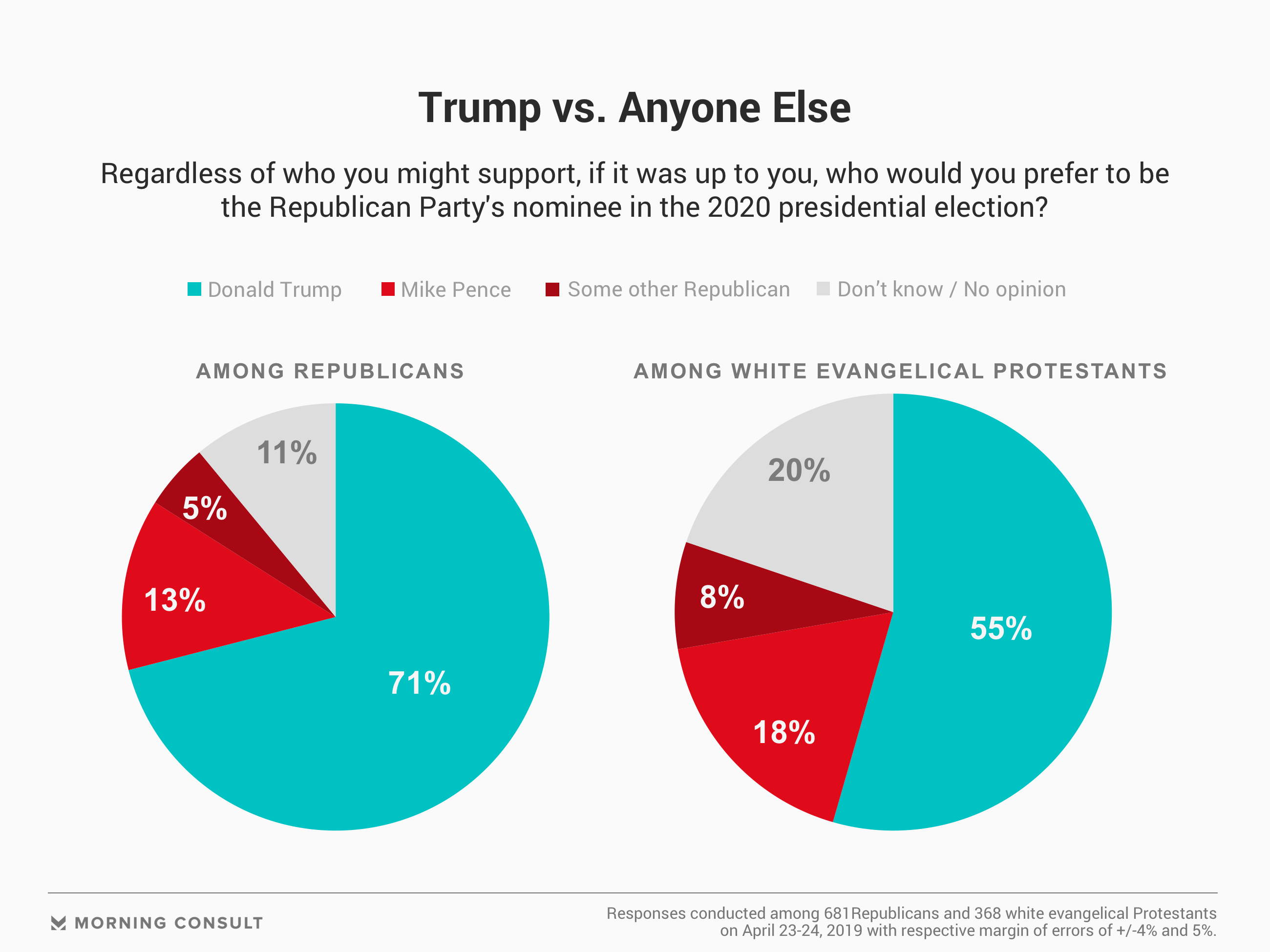

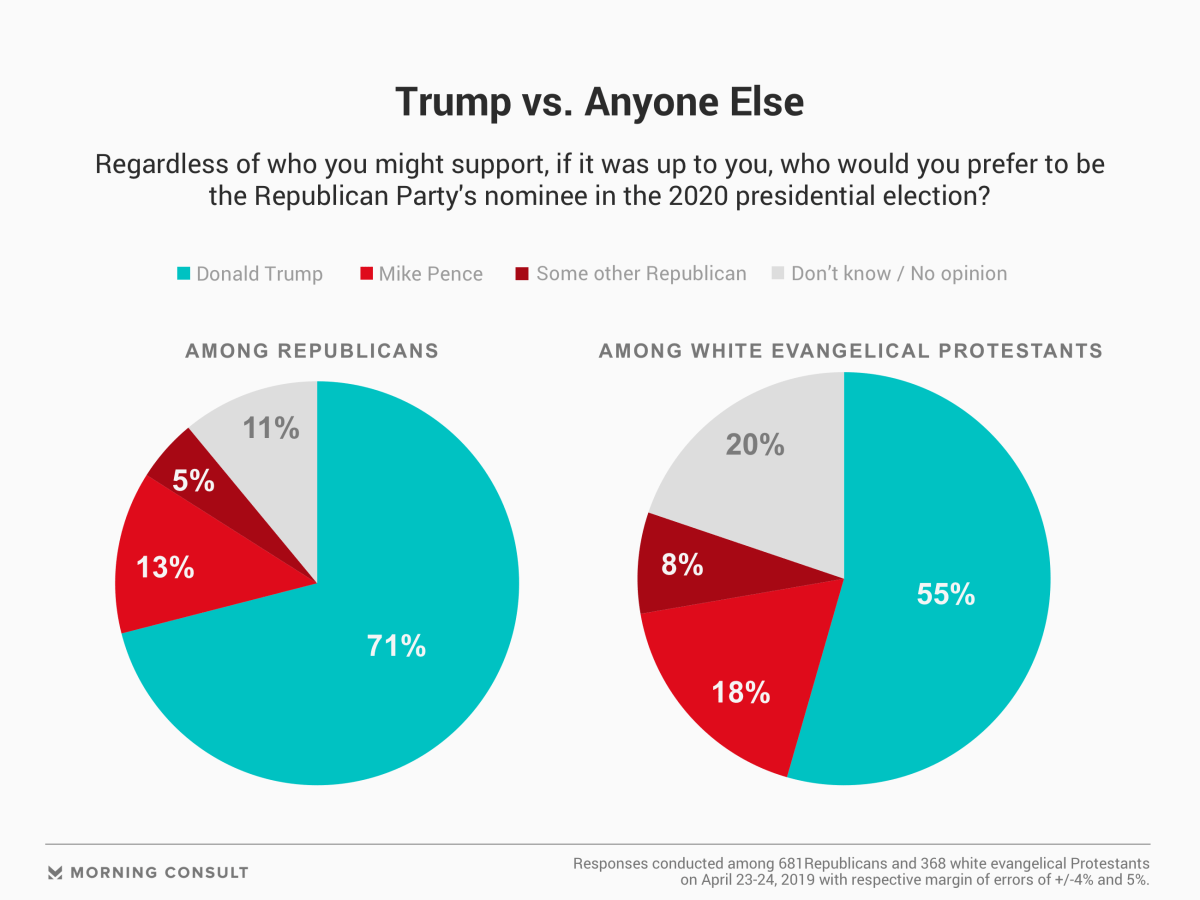

A Morning Consult poll released last month found that white evangelicals are significantly less likely than Republicans to want to see Trump as the GOP nominee next year: 55 percent versus 71 percent.

During the 2016 presidential election, polls similarly showed a majority of white evangelicals were dissatisfied with both major candidates on the ballot, though they ended up supporting him by a high margin.

The scenario that year ultimately brought new attention to a longstanding dilemma for Christians: how to bring their faith convictions to bear in politics when the candidates or the parties don’t fully align with what they believe.

“Even in the moments of frustration and lament over the current state of national politics and evangelicals’ role in it, the changing conversation since 2016 has given me hope,” said Kaitlyn Schiess, Dallas Theological Seminary student and author of a forthcoming book on spiritual formation and political engagement. “Younger evangelicals in particular are hungry for more conversation and ready to have an increased role in shaping the church’s response to political issues. … The conversations on my conservative seminary campus are more about how to come up with better theological guidelines for engaging politics than another set of policies to support.”

Kathryn Freeman teaches workshops on faith and politics as public policy director with the Baptist General Convention of Texas’s Christian Life Commission. She told CT that since the 2016 election she has seen political engagement deepen, with more fellow believers recognizing their political blind spots and challenging their own beliefs.

“So many Christians go to churches, Sunday school classes, Bible studies where they are never even taught how holding up every aspect of their life next to Scripture includes public policy and their vote,” she said. “I think even reading more broadly, asking questions that have never been asked before, are all positive signs of a shifting conversation.”

Those kinds of lessons on biblical applications give Christians greater confidence to speak openly about where they may disagree with elements of their party’s platform. Pro-life Christians find themselves in a precarious position in the Democratic Party, for one, which is growing more strident in its support of abortion as a right. Meanwhile, Christians who favor refugee resettlement and policies that prioritize family unity tend to conflict with the Republican Party and the Trump administration’s immigration stances.

Azusa Pacific University political science professor Douglas Hume said without a “true ‘home’ for evangelical voters in either of the major political parties,” evangelical voters have focused in on certain policies rather than wholeheartedly endorsing a moral leader. “I do not think it is a case of evangelicals simply blindly following the Republican nominee, but rather a difficult choice sometimes ending with choosing the lesser of two evils,” he said.

Some researchers suggest that Christians’ difficult choices and exceptional positions in this political era make the church a positive force working against partisan divides.

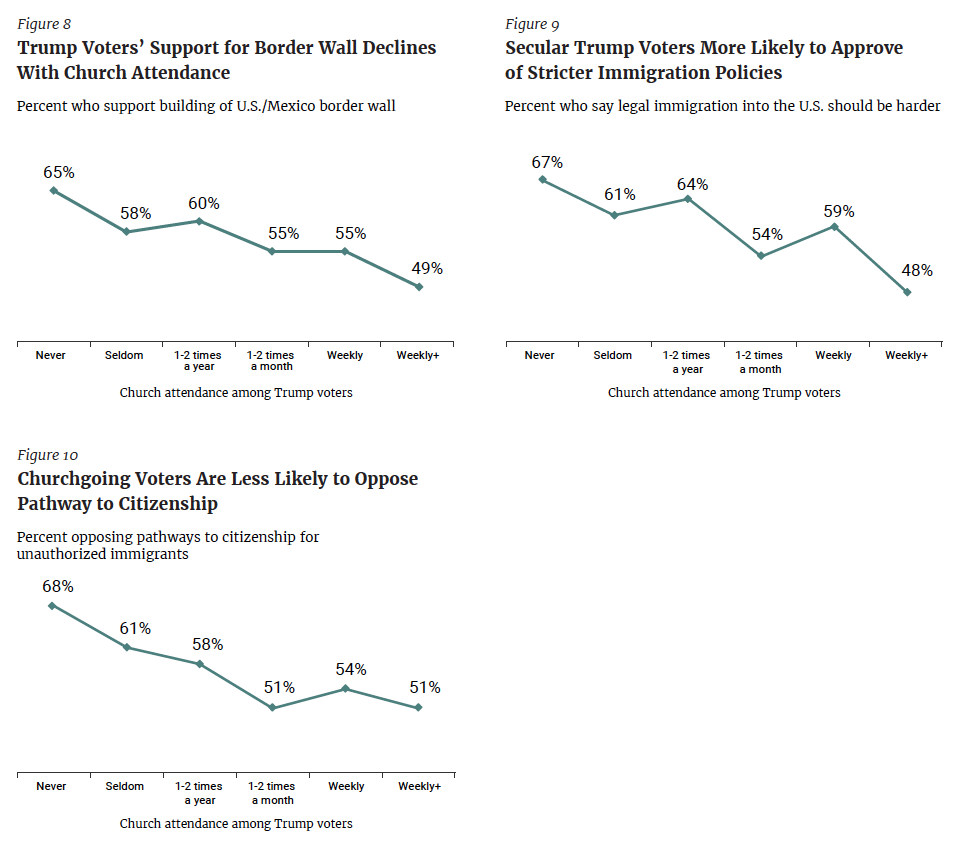

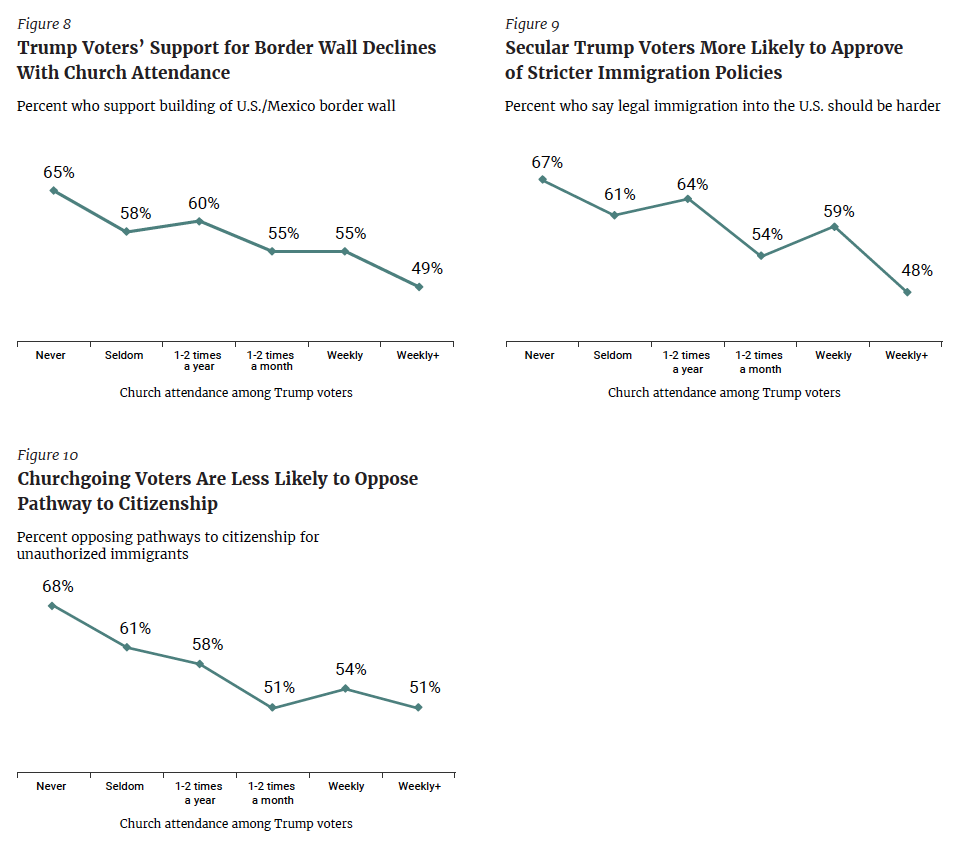

Emily Ekins, researcher and polling director at the libertarian Cato Institute, found that among Trump voters, those who attend church more regularly have more favorable views of racial and religious minorities, are less supportive of stricter immigration policies, and are more concerned about poverty.

Because of these more moderate positions among weekly-or-more churchgoers—across races and affiliations—she concluded that the church “may have a positive impact on social conflict and reduce polarization.”

That’s certainly the hope for some white Southern Baptist leaders who have spoken up to discuss how defending or supporting Trump can be perceived by non-Anglo and immigrant members of their congregation.

David Platt, pastor and former International Mission Board president apologized to members of McLean Bible Church who were hurt by his prayer for the president during an impromptu visit on June 2.

Greear brought up the “quiet exodus” of black evangelicals after the 2016 race during a panel at the SBC annual meeting this week. (Black Protestants were even more unified in their support for Hillary Clinton than white evangelicals were for Trump.)

“We’re getting ready to head into Donald Trump running for reelection,” the SBC president said. “I know that none of us what to see another massive exodus in this and we want to go forward in unity… without compromising our convictions.”

George Yancey, sociologist at Baylor University, suggested that seeing some Christians’ relentless defense of Trump throughout his presidency been more “disheartening” to African American churchgoers than the vote. “If you’re going to vote for him, then don’t be silent when he does things that we know are wrong,” he said.

The panel, which included Yancey along with two fellow African American leaders and two white leaders, agreed that it was crucial for churches to foster dialogue and understanding between Christians from both parties rather than seeing those from the other side as enemies.

“Do not make the political… spiritual,” said former SBC president and Georgia pastor James Merritt. “It is not Politics Above All. It is not even Supreme Court Appointments Above All. It is the Gospel Above All.”

But is that stance easier to take when the White House isn’t up for grabs?

“The political campaign of 2020 has potential to be really divisive,” particularly if SBC leaders push to invite candidates to the meeting, said Dave Miller, an Iowa pastor and editor of SBC Voices.

“We are at our best when we focus on eternal things and not political things.”