In 2018, Britta Wallbaum and Lindsey Goetz traveled to a worship conference in Nashville. They hoped to come away with new resources to engage children in musical worship at their Presbyterian church in Aurora, Illinois. As they browsed merchandise for leaders displayed in the rows of vendor booths, neither could find the item they had hoped for: a hymnal for children.

“There were zero resources to share with kids,” said Wallbaum. “There were songbooks [for children] with sheet music but no ways to actually engage kids with them.”

The two friends wandered the exhibit hall separately, not knowing that the other was looking for the same thing. When they realized their common goal, it seemed like a divine appointment. They decided to make the resource they wanted for their church and for their own children.

The Gospel Story Hymnal is the product of years of writing, illustration, and curation by Wallbaum and Goetz, who formed Word & Wonder to provide resources for worshipers of all ages, including children.

Crowdfunded by a Kickstarter campaign, the hymnal is a collection of 150 hymns, including centuries-old mainstays like “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” and “All Glory, Laud and Honor” and more recent works like Michael Card’s “Barocha.” It also contains a schedule that families can use to work through each hymn and the accompanying commentary over a three-year period.

There are five sections in the hymnal: “Creation,” “Rebellion,” “Redemption,” “Already, but Not Yet,” and “Restoration.” Wallbaum and Goetz wanted the hymns to help tell a broad, unified story.

“The Bible isn't a bunch of disconnected stories with good morals. It’s an interconnected story that all points to Jesus. Somehow I had missed that for the first 30 years of my life,” Wallbaum said. “So, this hymnal resource … We needed to build that idea of this overarching story into it—the gospel story, supported by all these different hymns and themes.”

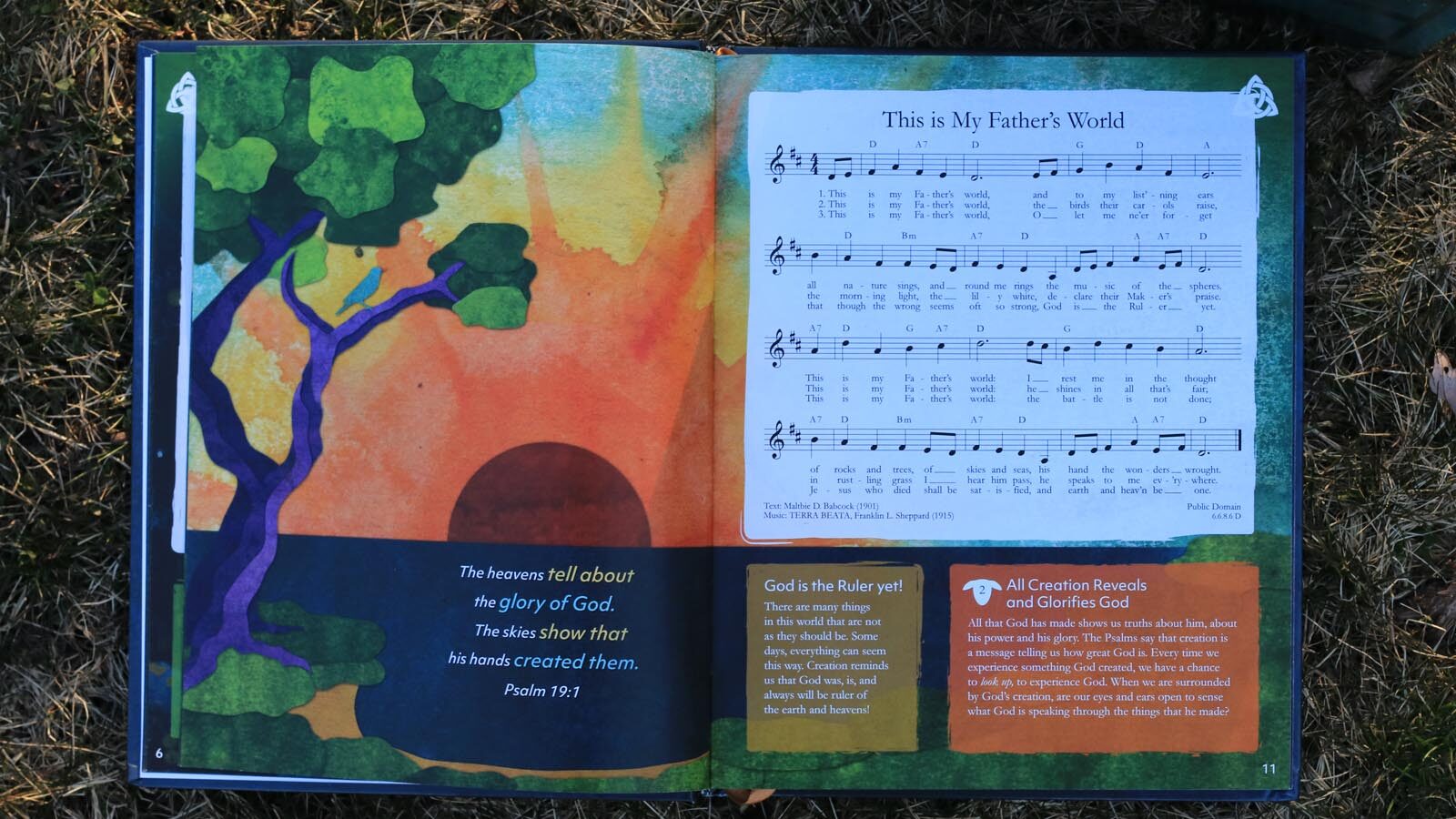

The hymn settings appear alongside Wallbaum’s vibrant watercolor illustrations and original commentary by Goetz.

Wallbaum, an architect, felt inspired to provide the artwork for the book herself. She spent months experimenting with different techniques and styles before developing a watercolor collage process inspired by Eric Carle.

“Each hymn has additional commentary regarding its theological importance, word definitions, applicable context information, scripture references, and/or worship notes, all written at an elementary level,” according the Word & Wonder website.

The authors did not alter or simplify the hymn texts for children. Wallbaum and Goetz believe that there is a benefit to having children sing the original words, even if they are challenging.

“You don’t grow out of hymns; you grow into them,” Goetz said. “As we journey in our life with God, the hymns can unfold greater meaning to us. They are pieces of faith formation that can grow with you.”

Rather than offer simplified hymns, Wallbaum hopes that her original illustrations and the accompanying commentary and scripture will draw children in and impart a sense of belonging in what can sometimes feel like “grown-up church.”

Goetz, the children’s minister at First Presbyterian Church in Aurora and spiritual director of Word & Wonder, believes strongly in the importance of multigenerational worship.

According to Goetz, “a better indicator of whether a high school student will remain a Christian after they graduate is whether they worshiped with their church community, not whether they attend youth group.”

Goetz, who is working toward a master’s degree in educational ministries through Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, spends a lot of time thinking about how childhood experiences in the church shape lifelong faith.

“If our church worship services are not welcoming to children, they need to change. What we see in Scripture is this call for the people of God to worship together.”

For both Wallbaum and Goetz, hymns have been powerful agents of spiritual formation. Wallbaum’s love of hymnody developed while she was a college student at Wheaton. Some of her professors would begin class by having students sing a hymn together. She was introduced to her favorite hymn “Be Still, My Soul” by her computer science professor, who had the class sing it at the beginning of a course meeting. When she got married, Wallbaum walked down the aisle to the hymn.

“It speaks to my soul, and it has walked me through so many phases of my life,” Wallbaum said.

In The Gospel Story Hymnal, “Be Still, My Soul” appears with an illustration of Jesus calming a storm.

Goetz has seen the enduring power of hymns in her life and in the lives of family members who walked with God for a lifetime.

“When someone has dementia, you watch them decline for years,” Goetz said, sharing the story of her grandfather’s death and the role singing hymns had in his final days.

Goetz remembers singing around her grandfather’s bed as he was receiving hospice care. She remembers the late afternoon light and the sound of her family singing hymns together, including “And Can It Be.” She remembers the sound of her father’s strong, deep voice and her aunt’s clear, confident harmonies.

“My grandma’s voice was cracking with tears. We couldn’t hear my grandpa, but his mouth was moving with the words we were singing.”

For Goetz, the memory of her grandfather recalling the words of hymns of the faith in his last hours powerfully illustrates the unique resonance and endurance of hymnody.

Now that The Gospel Story Hymnal is fully funded for a run of 3,000 copies, Wallbaum and Goetz expect books to be printed and shipped by September 2023. Wallbaum is finishing the final illustrations and is working on finalizing copyright licensing for all 150 hymns—no small feat. While many are in the public domain, 64 of them are still under copyright, and many of those have more than one copyright holder.

“It’s close to 100 copyright agreements I’ve ended up getting,” said Wallbaum. “For some I've actually had to get in touch with all the different songwriters, make a copyright license, and meet with them to sign. It's been … It's been a process.”

The creation of The Gospel Story Hymnal has been a rewarding and demanding undertaking for the authors. Goetz said that the prospect of giving this resource to churches looking to be more welcoming to children makes all the labor worthwhile.

“What I have seen at my church, in a congregation where children are welcomed and included—and of course we are still growing in this—I see children who can conceive of themselves as meaningful and important parts of the church,” said Goetz.

Goetz and Wallbaum, both mothers of young children, hope that The Gospel Story Hymnal will become a physical indicator in pews and seatbacks that children are welcome in the sanctuary.

“Experiencing belonging is one of the most important parts of how early faith develops. What's kept me going is the idea of seeing these [hymnals] in the pews and knowing that a child will open a book that's in the pew and say, ‘Oh, this is for me.’”