On Good Friday in 1963, eight white Alabama clergymen published an open letter in Birmingham calling for the Black community to cease their civil rights demonstrations.

These church leaders—from Methodist, Episcopal, Presbyterian, Baptist, Catholic, and Jewish traditions—advised that “when rights are consistently denied, a cause should be pressed in the courts and in negotiations among local leaders, and not in the streets.”

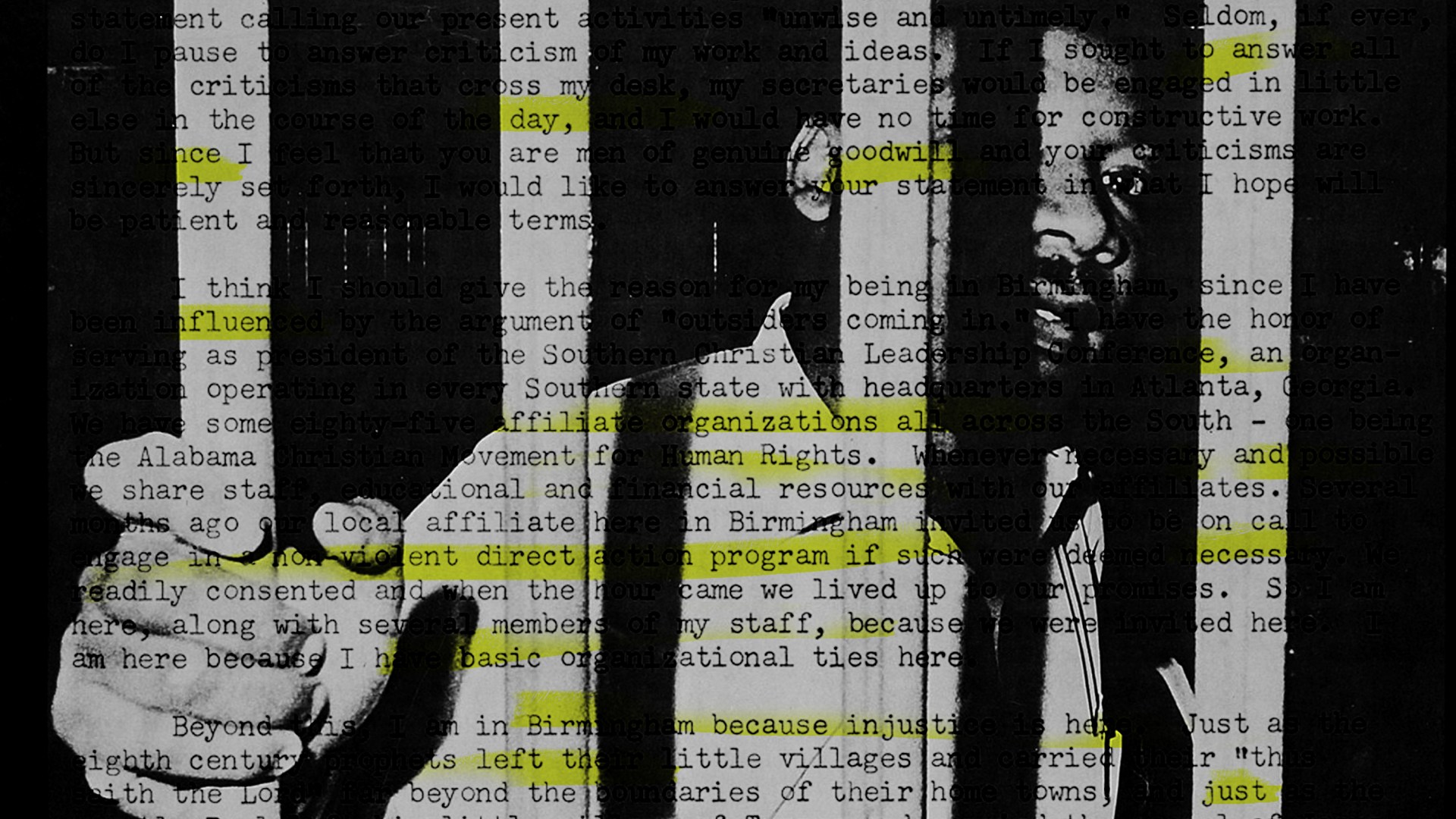

In response, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. penned a timely message—beginning on the margins of newspapers and then on smuggled-in scraps of paper—not knowing the profound impact it would have for generations to come. His “Letter from Birmingham Jail” is said to be the most important document of the civil rights era, compared by some to Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence for its impactful call for social change.

Although the “separate but equal” segregation law had been struck down a decade earlier through the landmark case of Brown v. Board of Education, some cities and states were resistant.

In Birmingham, one of the most segregated cities in America, notorious local safety commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor and other white segregationists got a state judge to pass a temporary injunction banning all pro-integration activity. And after leading a peaceful march, King and other protesters were arrested.

From his cell, King made a compelling argument for the importance of peaceful, public protest in the pursuit of justice. He explained the four steps of nonviolent activism: collecting facts to determine whether injustice exists, negotiating with local officials to work toward just resolution, practicing restraint when actions are taken against you, and raising awareness to drive more effective negotiation.

King began his letter by expressing his solidarity with the Black community in Birmingham, which had gone through all of these steps only to be met with countless broken promises: “For years now I have heard the word ‘Wait!’ … This ‘Wait’ has almost always meant ‘Never.’ … ‘Justice too long delayed is justice denied.’”

He expressed his frustration and disappointment with two particular groups of people that often intersected: the white moderate and the white church.

Accusing the white moderate of caring more about “a negative peace which is the absence of tension” than “a positive peace which is the presence of justice,” King further explained that “shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.”

King also shared his “deep disappointment” at the complicity and complacency of the white church—a discontent that was possible only because of his deep love for the church, as a third-generation pastor raised in its pews. He contrasted believers in the early church—who were eager to transform immoral practices in their society—with the contemporary Christian church, which had become an “arch-supporter of the status quo” with its “silent and often vocal sanction of things as they are.”

He then posed a question that is still being asked today: “Is organized religion too inextricably bound to the status quo to save our nation and the world?”

Many pastors and members of white churches today use quotations from King in their sermons, writing, and social media posts. But if we are going to change power structures that perpetuate racial injustice, we must move from memorializing toward modeling King’s message and call to action.

As Esau McCaulley wrote in his piece for Martin Luther King Jr. Day last year, “If remembering King means anything, it involves a sanctified dissatisfaction with the status quo.”

In a 2021 Pew Research poll, over a year after the George Floyd protests, 65 percent of Black Americans reported that the renewed awareness of racial inequity did not have an impact on the lives of their community—compared to 2020, when 56 percent expected policy changes would improve Black people’s lives.

One problem is that some white communities, both Christian and non-Christian, are worried about their own marginalization and blind to the marginalization of others. Another issue is the ongoing lack of awareness of the ways racial and economic systems perpetuate injustice in communities of color.

When confronted, some will blame partisan politics for ineffective change. Political divisions have always caused people to hold fast to one side or another, even at the expense of violating the humanity of others. But silently staying somewhere in the middle and watching, hoping, or grieving is not a sufficient response for Christians. Instead, we must ensure justice in the courts so that all people are treated fairly.

As King wrote in his letter, “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Injustice does not just happen, and it does not repair itself. If we want history to tell a different story of the white church, we must join the men and women working to repair the unjust systems in our country—especially those individuals who belong to the body of Christ.

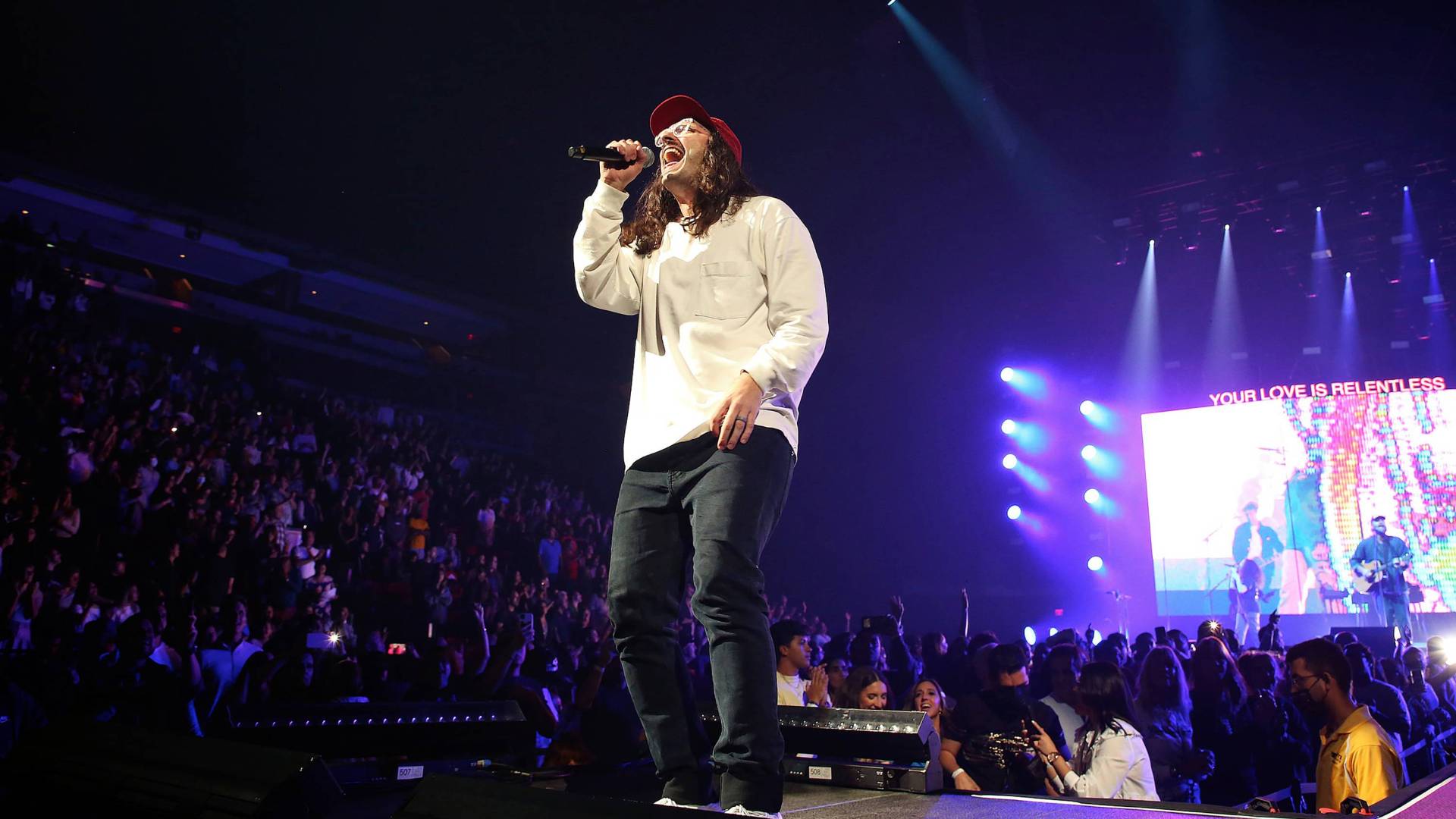

During this Easter season, pastors from the Black church tradition are marching at state capitols, much like King did 60 years ago. They are working to ensure that all voices are heard; that books are not banned; that their history is not erased; that their right to vote is protected; that financial barriers to homeownership are removed; and that competitive wages, education, skills, and capital for wealth creation are available to all.

The Black community is not the only group in our country that faces injustice.

For instance, pastors from Latino evangelical churches in Florida are mobilizing to protect their own communities and churches from unjust policy proposals that would criminalize providing car rides and opening their homes to undocumented immigrants. Such a law would make it a felony to extend hospitality, whether one is aware of the person’s immigration status or not.

The fight for civil rights is not the story of the past; it remains very much alive today. Throughout history, it has never been just one issue at one time, in one location, affording one solution, march, mobilizing effort, or request. It has always been a series of necessary actions, spanning decades.

In all such matters, the white church needs to care enough to listen, learn from, and work toward a more proximate justice. In joining this effort, we better understand the prophet Amos, who bore witness and opposed the extreme injustices of his day when he cried, “Let justice roll on like a river, righteousness like a never-failing stream!” (5:24).

At the end of his letter, King reorients his personal disillusionment by recalling the “church within the church, … the true ekklesia and the hope of the world.” Regardless of its size, this group is composed of those who benefit from the status quo working alongside those who are impacted by injustice and unrighteousness. Their witness is what King calls “the spiritual salt that has preserved the true meaning of the gospel.”

The work of change has always been done by a remnant. And together, we can carve a “tunnel of hope through the dark mountain of disappointment” by picking up the mantles left by those who have gone before and working for justice today.

Michelle Ferrigno Warren is the president of Virago Strategies and helped found Open Door Ministries. She is the author of Join the Resistance: Step Into the Good Work of Kingdom Justice (IVP, 2022) and The Power of Proximity: Moving Beyond Awareness to Action (IVP, 2017).