Churches across the US and Canada sang, “Refiner’s fire / my heart’s one desire / is to be holy” for a full decade after Vineyard worship pastor Brian Doerksen released it in 1990.

“Overcome,” written by megachurch worship leader Jon Egan in 2007, was just as popular. But North American churches only sang, “worthy of honor and glory / worthy of all our praise / you overcame” for about three years.

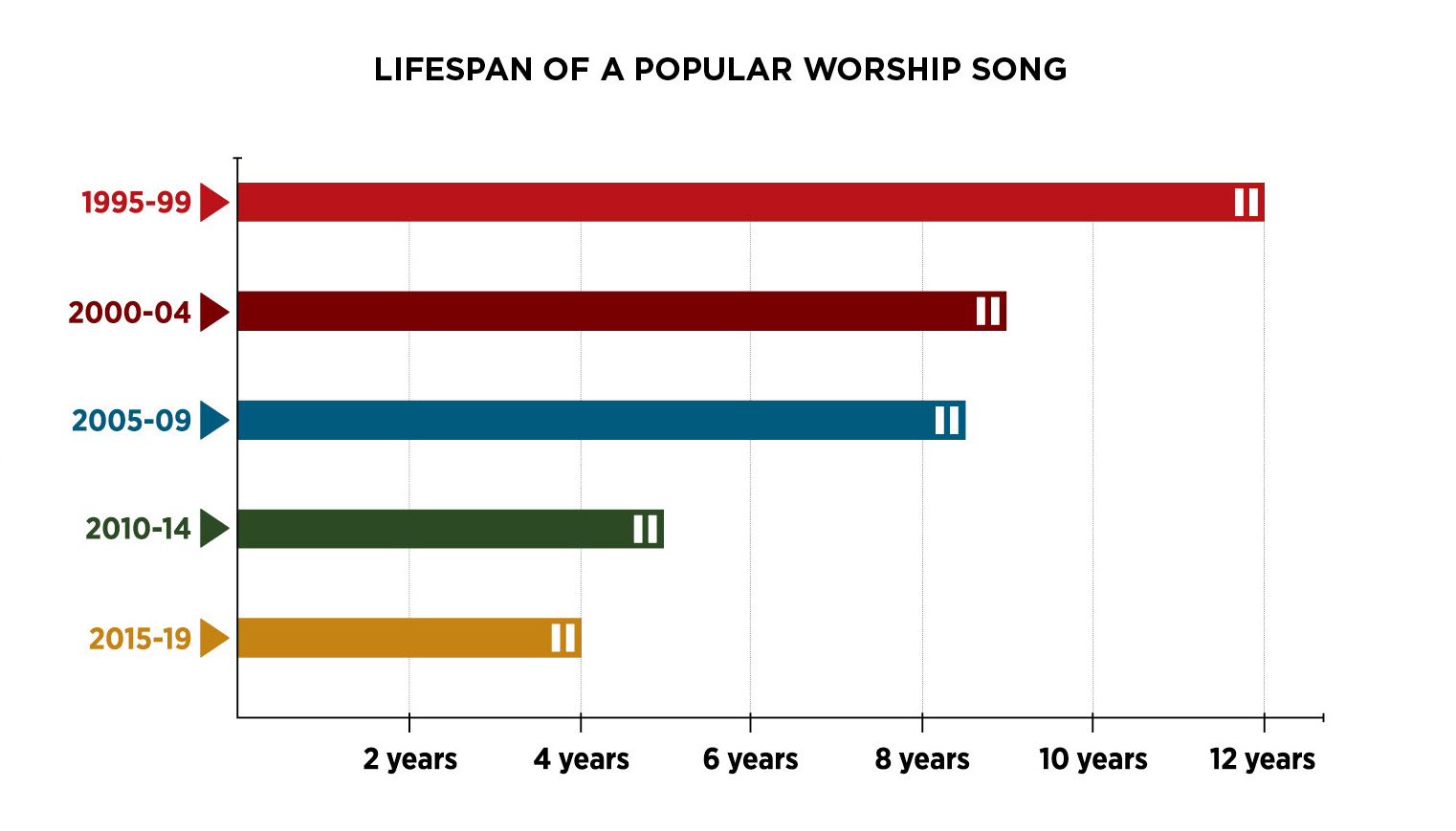

Worship songs don’t last as long as they used to. The average lifespan of a widely sung worship song is about a third of what it was 30 years ago, according to a study that will be published in the magazine Worship Leader in January.

For the study, Mike Tapper, a religion professor at Southern Wesleyan University, brought together two data analysts and two worship ministers to look at decades of records from Christian Copyright Licensing International (CCLI). The licensing organization provides copyright coverage for about 160,000 churches in North America and receives rotating reports on the worship music that is sung in those churches, tracking about 10,000 congregations at a time.

Looking at the top songs at those churches from 1988 to 2020, the researchers were able to identify a common life cycle for popular worship music, Tapper told CT. A song typically appears on the charts, rises, peaks, and then fades away as worship teams drop it from their Sunday morning set lists.

But the average arc of a worship song’s popularity has dramatically shortened, from 10 to 12 years to a mere 3 or 4. The researchers don’t know why.

Marc Jolicoeur, who worked on the study, said the data confirmed what many music ministers have felt intuitively. It matches his experience as a Wesleyan worship pastor in New Brunswick, Canada.

“I got three emails from people in my church this week saying, ‘Have you seen this new song?’” he said. “My pastor isn’t saying, ‘I need the latest and greatest worship song this week,’ but at the same time, a song seems stale, and it seems stale more quickly than it used to.”

The increasing speed of song turnover seems connected in some ways to changing musical styles, Jolicoeur said. The durable verse-chorus-verse model for a church song has given way to music like Elevation Worship and Maverick City’s 2021 release “Jireh,” which has verses that sound like choruses, followed by actual choruses, followed by multiple bridges—three or more, depending on who is preforming. “Jireh” is “a juggernaut of a song,” according to Jolicoeur, but it’s also an example of musical innovations that rapidly age.

“Songs have always changed,” Jolicoeur said. “But we want songs to change faster now. It’s the culture. It’s the soup we’re swimming in.”

Scholars who study Christian music, however, say it is probably not the songs themselves that are driving the change, but the way music is distributed.

In the ’90s, worship leaders learned of new songs at conferences. They then taught a song to their congregations by playing it three weeks in a row, skipping a week, playing it again the following Sunday, and then putting it into regular rotation. It might have stayed in rotation for a dozen years.

Now, worship leaders learn of new music when it comes out on Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon, iTunes, Pandora, and YouTube. Many Christians will stream a new song for weeks before they hear it in church. And the whole process moves at a different speed.

“It’s tied to the mechanisms of how people are discovering music, and how American consumption patterns are changing,” said Leah Payne, a theology professor at Portland Seminary who is writing a history of contemporary Christian music. “This is worship that is sensitive to consumption patterns.”

The new distribution model is organized around the “album drop” as an event, said Adam Perez, a postdoctoral fellow in liturgical studies at Duke Divinity School. That means everyone, from songwriter to worship leader to churchgoing fan is focused on the next new thing.

That model undercuts the older value of a common musical repertoire and accumulating a common stock of songs. But it also helps many churches fulfill their mission of reaching out and including new people.

For many congregations, it’s important to speak to the present moment, Perez said. Worship leaders are not concerned about whether a song that works today will also be relevant in 2033. It just needs to connect today. That gives them more freedom and encourages them to embrace new styles, keeping an ear out for songs that will appeal to new people.

Not everyone loves that, though. Some churches, of course, completely opt out of contemporary worship music. And those that do sing worship songs sometimes still feel the rapid turnover can create a sense that nothing is solid and nothing lasts, said Nathan Shaver, a Christian songwriter and musician who now pastors a church in Indianapolis. Constantly changing styles and fashions can leave people feeling like faith itself is a fad.

Worship Leader

Worship Leader“There is a reason some people are rediscovering the psalms and singing the psalms,” he said. “Something that’s familiar and ancient, that hasn’t changed and isn’t going to change tomorrow? I wonder if there isn’t a need for that.”

Shaver ultimately decided he needed to ignore market pressures when he wrote his music. He tried to approach it as a craft and a passion.

“You have to write because you love it. That’s where the best worship songs come from,” he said.

Mark Nicholas agrees. Vice president of publishing at Integrity Music, Nicholas said artists can get caught up in chasing after a hit and spend all their time analyzing popular themes and trends, instead of focusing on what God wants them to write.

“The struggle of our business—the struggle for any business, really—is holding our ideals in tension with the realities of economics,” Nicholas said. “You can sniff when a song is being constructed. When a song is written to meet a need in someone’s life, those songs carry something.”

That something might be sung in churches for 10 years or for just a few. But it doesn’t really matter, Nicholas said, as long as the right song connects with people at the right moment.

He recalled a time when he put his son to bed for the very first time after adopting him at age four. A line from the hymn “Great Is Thy Faithfulness” came to mind: “Blessings all mine and ten thousand beside.”

He couldn’t remember the last time he’d sung that, but it didn’t matter. It came to him when he needed it.

He hopes the songs that Integrity puts out into the world have that kind of impact, creating that kind of moment when a snatch of a line opens up a heart to God.

Last year, as COVID-19 infected thousands and then hundreds of thousands died, churches across North America sang, “Way maker, miracle worker, promise keeper / Light in the darkness, my God.” The song was promoted by Integrity, which partnered with the song’s creator, Nigerian worship leader Sinach, to have it covered by Michael W. Smith and the band Leeland. The song appeared on CCLI’s list, rose, and for a time held the top spot.

It might not be there next year. Churches might not need that song then.

But Nicholas thinks it still will have mattered. “Songs that accompany us in moments will stick with us, even if they fade a little faster,” he said. “‘Way Maker’ will mean something to people on their deathbed because it got them through a hard time.”

Whether churches sing it for a year or 10,000, that may be all you can ask a worship song to do.

Daniel Silliman is news editor of Christianity Today.