The Cosmos Is More Crowded Than You Think

A very important and enjoyable article about heavenly beings I don’t ordinarily think about. What’s so strange is that the illustration associates angels with wings, something the Bible never does! If someone wants wings and Biblical examples, they must consider cherubim or seraphim, not angels.

Jeffrey Wurtz Cupertino, CA

John Stott’s Global God

John Stott taught two classes, Sermon on the Mount and Pastoral Epistles, for one quarter in 1972 at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School in Illinois. I was fortunate to take both. Along with John’s compassion, I sensed his unique God-given authority and mission described in the article. John strove to help build the global church and study birds in joyous combined adventure.

James Hilt Sheboygan, WI

If I Had to Bow to an Idol, It Would Be the Sun

I have pondered such thoughts myself for years, wondering what it would have been like to worship some natural object. I too have found that meditating on the sun shows me God’s nature in a unique way. I appreciated Wilson’s point that the sun gives us an image of God’s “mysterious combination of immense distance and felt presence.” I thank him for putting such a clear reminder of himself in the sky where we can see it every day.

Martha Knutson St. Paul, MN

How White Rule Ended in Missions

I don’t disagree with the article’s content. However, the title seems incongruous with the content of the article. My concern is not only the lack of harmony between title and content but that those who notice the prominently displayed title and do not read the article may well come away with the impression that white rule in global missions has fully ended.

Barney Ford Wake Forest, NC

Evangelicals Have Made The Trinity a Means to an End. It’s Time to Change That.

In “Evangelicals Have Made the Trinity a Means to an End,” Matthew Barrett includes me, along with others, as a culprit. After summarizing what I say about the Trinity and the church, he concludes: “To meet the agenda of the church, the Trinity has been redefined.” It is a serious charge to say that someone is deliberately crafting and using God for their own ends. To make the charge stick, Barrett takes the title of my book After Our Likeness (a quote from Genesis!) as his important “argument.” Barrett also claims that I insist that “there must be a direct correspondence between the type of community we see in the church and the Trinity.” In that book and elsewhere I say the exact opposite. In explaining that I intentionally use God as mere means for my own ends, he has used me as mere means to his ends.

Miroslav Volf New Haven, CT Yale University Divinity School Yale Center for Faith and Culture

Thank you, CT, for Barrett’s article engaging in “The Battle for the Trinity,” the title of a book by the late Donald G. Bloesch, theologian and past CT corresponding editor—who also warned of the “drift” away from the historical understanding of the ontological nature of the Trinity, which in Moltmann’s view has led to a “panentheism” where “God and the world are not identical, but interdependent”! I hope Barrett’s critique of these revisionists will challenge us to consider the negative consequences.

Charlene Swanson Isanti, MN

When we bend to societal or cultural views and manipulate the gospel to satisfy society or present culture viewpoints, or the viewpoints of liberation theology, we are limiting the scope of the gospel and ignoring how the gospel may apply to many others, not just those under oppression.

Dennis Wright Dunnville, Ontario

It’s one thing to draw applications from the Bible regarding current issues and policies. It’s something else altogether when we forget that our interpretation of the Bible may not be as accurate as the Bible itself. I cringe when I hear people citing the Bible to justify things which may reflect more of their ideology than Christ.

David Graf (Facebook)

The Poet Who Prepared the Ground for the Sexual Revolution

A one-sided presentation of the unregenerate male’s self-centered wishful thinking, such promiscuous behavior costing him nothing. Though not aimed at moralizing, it’s to be hoped the article didn’t succeed in only presenting a tantalizing lifestyle to the unwary reader.

Richard Strout Sherbrooke, Quebec

Learning to Love Your Limits

I found myself frustrated reading your interview. The focus of Kapic’s responses was entirely on how our individual theology can help us make better individual choices. However, much of modern life is overwhelming because of circumstances beyond our individual control. I would like a theology that helps me cope within systems designed to drive me bonkers at best and into depression at worst while pointing Christians toward how to support just societal changes that help everyone thrive.

Stephanie Pease Boulder, CO

I Entered Prison a ‘Protestant.’ I Left a Christian.

Thank you for sharing this article. The Gideon Bible has shown up a few times in my journey too.

Guillermo Acosta (Facebook)

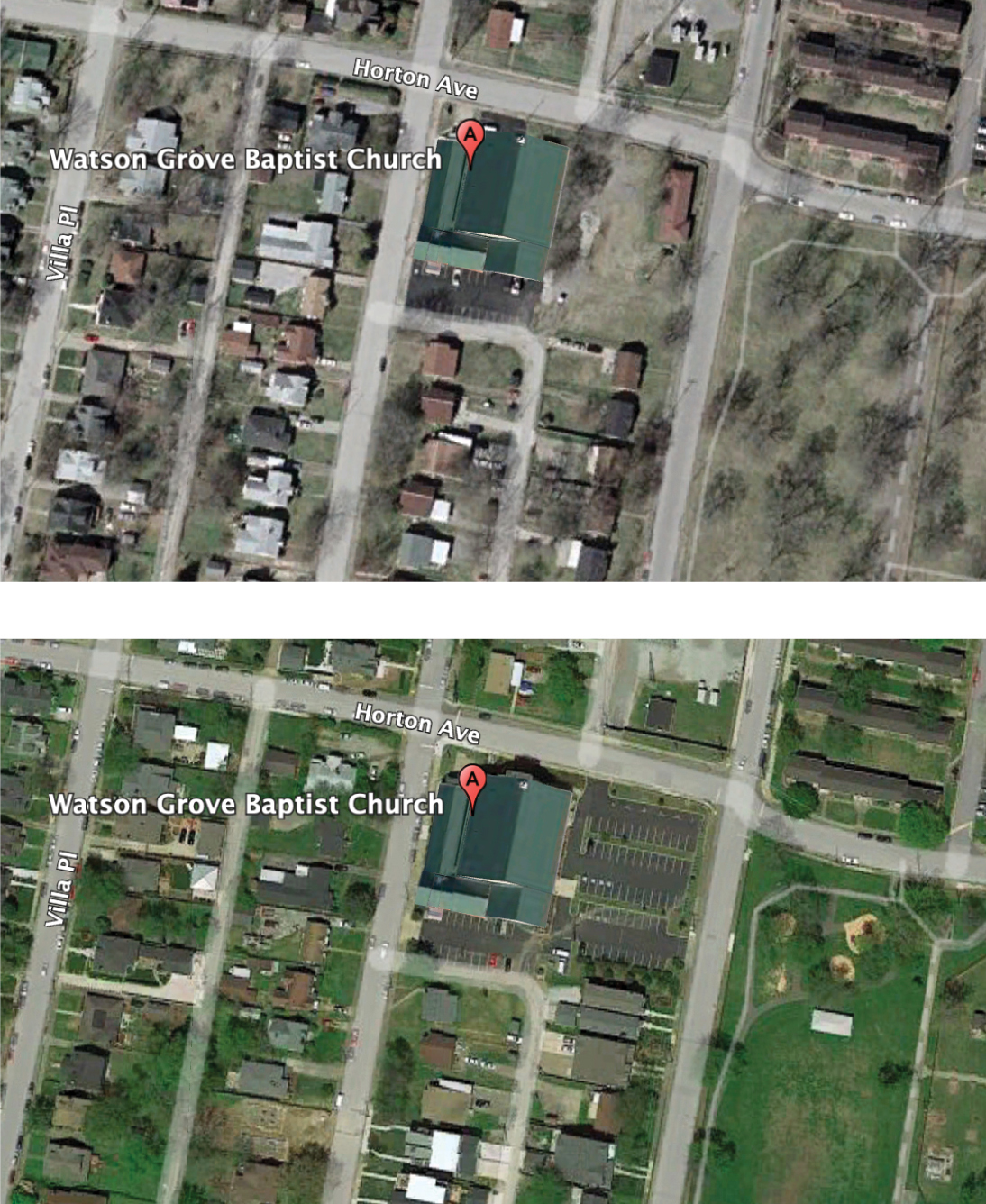

Correction: In the March issue article “Hard Labor,” the incorrect location was given for New Horizons Ministries. Its headquarters are in Cañon City, Colorado.