COLOMBO — Sri Lanka’s government said Tuesday it would take time to consider a proposed ban on the wearing of burqas, which a top security official called a sign of religious extremism.

The minister of public security, Sarath Weerasekara, said Saturday he was seeking approval from the Cabinet of Ministers to ban the outer garment worn by some Muslim women covering the body and face.

“The burqa has a direct impact on national security,” he told a ceremony at a Buddhist temple, without elaborating.

“In our early days, we had a lot of Muslim friends, but Muslim women and girls never wore the burqa,” Weerasekara said, according to video footage sent by his ministry. “It is a sign of religious extremism that came about recently. We will definitely ban it.”

However, government spokesman Keheliya Rambukwella said a ban was a serious decision requiring consultation and consensus.

“It will be done in consultation. So, it requires time,” he said without elaborating, at the weekly media briefing held to announce the cabinet decisions.

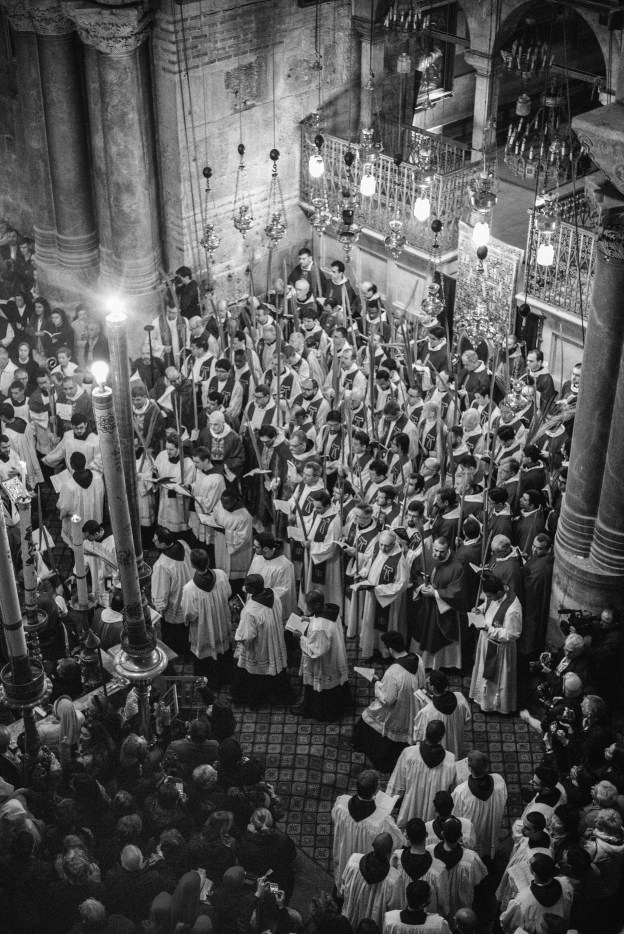

The wearing of burqas in Sri Lanka was temporarily banned in 2019 soon after the Easter Sunday bomb attacks on churches and hotels that killed more than 260 people in the Indian Ocean island nation. Two local Muslim groups that had pledged allegiance to the Islamic State group were blamed for the attacks at six locations: two Roman Catholic churches, one Protestant church, and three top hotels.

Earlier, a Pakistani diplomat and a UN expert expressed concern about the possible ban, with Pakistani Ambassador Saad Khattak tweeting a ban would only injure the feelings of Muslims. The United Nations’ special rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief, Ahmed Shaheed, tweeted that a ban was incompatible with international law and the rights of free religious expression.

Separately Tuesday, Sri Lanka’s Foreign Ministry said the government would take the time to consult with all parties concerned and reach a consensus.

Sri Lanka also has plans to close more than 1,000 Islamic schools known as madrassas because they are unregistered and accused of not following national education policy.

The proposal to ban burqas and madrassas is the latest move affecting the Indian Ocean island nation’s minority Muslims.

Muslims make up about 9 percent of the 22 million people in Sri Lanka, where Buddhists account for more than 70 percent of the population. Ethnic minority Tamils, who are mainly Hindus, comprise about 15 percent of the population.

Regarding the proposals, the National Christian Evangelical Alliance of Sri Lanka (NCEASL) told CT the group favors freedom of religion or belief.

“We believe it is a woman’s right to decide what she wears,” said Godfrey Yogarajah, NCEASL general secretary. “Also, if she has grown up wearing the burqa for religious reasons, then for the state to try and regulate is a violation of religious freedom.”

Regarding security concerns, Yogarajah—also the World Evangelical Alliance’s ambassador for religious freedom—noted that the suicide bombers in Sri Lanka have all been men “dressed in normal attire.” He also noted how Sri Lankans are currently required to wear face masks as they go about daily life.

“In this context, to propose a ban on Muslim women wearing burqas is not prudent,” he said, “and discriminatory.”

Additional reporting by Jeremy Weber of CT.