Patrice Hunt knows people wonder why she is working at Wycliffe Bible Translators, a black woman surrounded by white people. She’s asked God that question herself.

“Why did you make me black,” she said, praying in the mirror one morning, “if you’re just going to have me around white people?”

It doesn’t always happen this way, but she got an immediate answer. She felt God say, “There are things I need you to learn from them that your community can’t teach you.”

As the senior director of human resources in Wycliffe’s Florida office, Hunt has learned a lot of things. One, she told CT, is that God has equipped her and other African Americans for mission work.

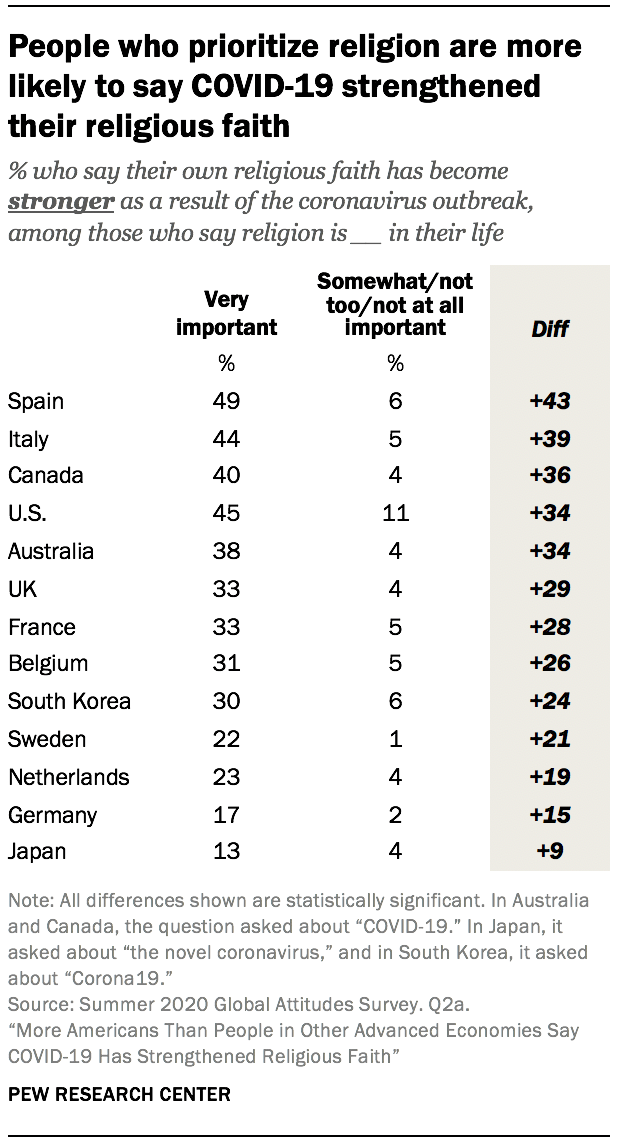

Some experts say that less than 1 percent of American missionaries are black. In many missions organizations, that actually seems like an overestimate. According to a 2020 report, the Southern Baptist Convention’s International Missions Board—the largest sending agency in the world—has 3,700 career missionaries and only 0.35 percent are African Americans.

The reasons are varied. Many African Americans who are called to ministry have prioritized the needs in their own communities, focusing on preaching the gospel or pursing justice locally. Global travel and exposure are a privilege and less accessible to racial minorities. The historic relationship between missions and colonialism is complicated, and missionaries, for many, are associated with the idea of a “white savior,” not a black Christian. Black churches have different traditions of giving, making the most common models of fundraising more difficult for African American Christians. And most missionary institutions and sending agencies are predominantly white and can be uncomfortable spaces for black people.

But young African American Christians are increasingly interested in international mission work, according to a recent Barna survey. Sixty-one percent of black churchgoers between the ages of 18 and 35 say they could become a missionary, depending on their sense of calling, whether or not they would be helpful, and the tasks they’d do on the field. By comparison, less than half of young white Christians who regularly go to church say the same.

“They’re becoming more missions and globally minded,” said Sherry Thomas, an African American missionary who has served for 22 years in African countries, most recently Nigeria. For many years, she said, the only missionaries she met were white, but now there seems to be a generational shift.

It could create an unprecedented opportunity, according to African American missionaries currently at work around the world.

“What has intensified is our voice,” said Ron Nelson, founder of Sowing Seeds of Joy, an organization that mobilizes and trains African Americans for overseas mission work. “Our voice has become more significant. Our voice has become more needed. That’s what has changed.”

‘We can connect like the others don’t’

Nelson notes that many African American Christians remain skeptical of missions. He remembers a black pastor telling him and his wife, Star Nelson, “I love what you’re doing, but missions is not our thing.” In fact, the Barna study shows that about half of young black churchgoers agree with the statement that “Christian mission is tainted by its association with colonialism,” and 40 percent agree with the statement that missions work has been unethical in the past.

But some say that because of the history of colonialism, slavery, and white oppression, black missionaries can be more effective than their white counterparts. Star Nelson said that in Haiti, there were people who were willing to listen to her talk about Jesus because she is black.

“Most people know our African American story,” she said. “So, we can connect like the others don’t. Sometimes we connect in a way that is exactly what they need.”

The past generation of African American missionaries was mobilized with the phrase “blessed to be a blessing”—a call to use their relative wealth, education, and privilege to serve those in under-resourced areas. But today, black missionaries say that one of the important gifts they can bring to the world is an understanding of trauma, suffering, and loss.

“So many of our images of missions [show] the white person of middle-class status taking care of an Indian widow,” said Lily Field, executive director of Ambassadors Fellowship, an African American sending agency, at the recent virtual conference of the National African American Missions Council (NAAMC).

“I don’t relate to being the savior in this picture,” she said. “I relate to the sufferer in this picture.”

That can be a powerful point of connection, Thomas said. She has worked as a trauma healer in Mali prisons and recently started working with pastors in Nigeria to establish a trauma healing center there. Her skin color has been an advantage in the work, both because she personally knows the trauma that racism can bring and because she doesn’t have to deal with the additional distance that white people sometimes can’t overcome.

Diversity consultants assessing institutions

Some sending agencies, recognizing the value of African American missionaries and noticing their own lack of diversity, have started recruiting more black Christians to the mission field. The Southern Baptist missionary organization hired Jason Thomas to specifically engage with African American Baptist churches.

“This first year has been about building relationships and establishing trust in black and minority church-led communities,” he said. “There is no secret that we have had many setbacks this year with the pandemic, racial tension, and the last presidential election. But there has been amazing support from leadership at IMB and colleagues that all want to see a mission force that could make our Savior proud.”

Others, like Wycliffe, have hired outside consultants to assess the diversity, equity, and inclusion of the institutional culture, and examine the structures and systems that have made it harder for black people to thrive in their organizations. The NAAMC has started offering resources, coaching, and diversity training to help. The council’s 2020 conference drew a record number of attendees, both black and white.

Adrian Reeves, director of the council, said he is encouraged by the number of sending agencies that are pursuing diversity training and working to recruit more minorities into missions. But he also thinks it’s important that African American organizations, like the Nelsons’ group Sowing Seeds of Joy, rise up independently.

“It is great to see that African American churches are reaching out to an organization that looks like them and talks like them and is able to present missions,” he said.

Visions of reform

Many in the next generation of African American missionaries will likely seek to reform how missions are done. Whether they join new organizations started by African Americans or fill the ranks of white institutions, there is an interest in changing the status quo and developing new missionary narratives.

Mekdes Haddis, an African missiologist who created the online community Just Missions, said one thing a younger generation of missionaries might rethink is their approach to poverty. Growing up in Ethiopia, she understood poverty to mean a lack of community or exposure to abuse. But Western missionaries often seemed fixated on material goods and couldn’t see the local community resources that addressed physical needs, like the Orthodox Church steps where children were given food or coins.

African American missionaries have the potential to break from “missions as usual,” but first they have to wrestle with seeing themselves as potential missionaries, said Haddis, who is now based in South Carolina.

“A lot of African Americans or people of color don't end up on the mission field,” she said. “It doesn't fit us, you know? It's so white-centric culturally and financially. Like, ‘I can't raise funds to live off of.’”

Funding is seen as a major issue in recruiting more African Americans to missions. There are major differences in generational wealth between black and white Americans. African American pastors say their churches and members just don’t have as much money to give, and many black families see mission work as a luxury they can’t afford.

“Even in the world of missions, we’re trying to play catch-up,” Ron Nelson said.

The Holy Spirit moves

At Wycliffe, Hunt said it can be frustrating how slow change is in coming and how hard it is to build bridges in the midst of division.

“It’s work,” she said. “And it’s movement from everybody. If we would move closer to Christ, we would get closer to each other.”

She often goes walking on the beach to remind herself how big God is. And sometimes she remembers that the Holy Spirit can just move people.

“God literally plucked me out of my community,” she said, “and plopped me in a white community.”

If the next decades see a flourishing African American mission movement, there will be a lot more stories like that.