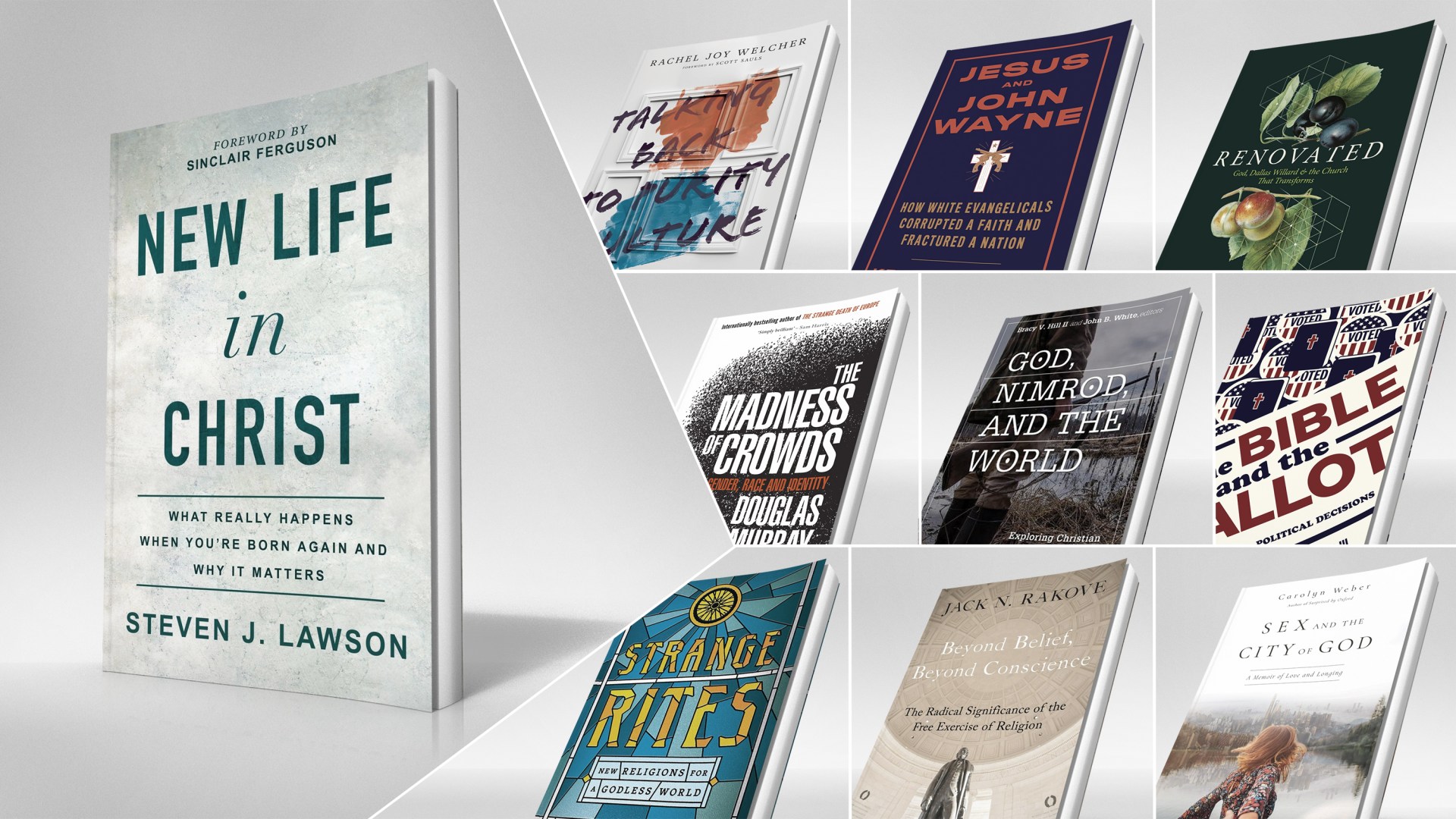

Perhaps, in the decades to come, some enterprising religious historian will study how the coronavirus pandemic of 2020 affected Christian magazine journalism. Fair warning: You won’t find anything terribly eye-opening in CT’s books coverage.

As the editor chiefly responsible for that coverage, I remember feeling a tad sheepish at our morning check-in meetings during those first few locked-down weeks in March and April. Updates from colleagues throbbed with urgency. They were commissioning timely op-eds analyzing the virus in all its theological and sociopolitical complexity. They were chasing down stories about believers manning the medical front lines and churches transitioning to online services. Meanwhile, my own work carried on as though nothing had changed.

At the time, all sorts of writers and bloggers were cranking out COVID-19-inspired reading lists. Some aspired to hyperrelevance, touting books on the science of contagion or the history of pandemics past. Others encouraged making the most of the leisure time afforded by stay-at-home orders—why not seize the chance to finally crack open that dusty copy of Moby-Dick or War and Peace? It all made me nervous that I was shirking my journalistic duty by sticking with regularly scheduled programming.

In the end, though, I’m glad our book pages weren’t swept up in the coronavirus riptide. Of course, much of that is due to forces outside our control—namely the fact that, beyond a few expedited pamphlet-style offerings from luminaries like John Piper and N. T. Wright, pandemic-focused titles weren’t yet rolling off the presses. For good reason, most books are slow in the making.

But more importantly, I was determined to preserve a degree of principled detachment from the rush of daily headlines. Our books coverage will always stay attentive to the news cycle—after all, we’re called Christianity Today, not Christianity in General. But even in moments of crisis, we won’t allow a myopic sense of What’s Happening Now to govern our priorities, as though books not speaking directly to the danger at hand are luxuries worth indulging in only after the danger has passed.

Hopefully, as you browse this year’s award winners, you’ll find a healthy balance between current events and eternal verities—between the news that keeps us informed and the Good News that keeps us rejoicing, in sickness and in health. —Matt Reynolds, books editor

Apologetics/Evangelism

Telling a Better Story: How to Talk about God in a Skeptical Age

Joshua D. Chatraw | Zondervan

For many believers today, the prospect of talking about God to friends, neighbors, and colleagues feels bewildering. Telling a Better Story illuminates a possible way forward. With a calm and sensible tone, Joshua D. Chatraw promotes a posture of invitation, taking seriously the spiritual thirst that is evident if you take the time to look. Chatraw urges Christians to pay greater attention to the dreams, aspirations, heartaches, and losses of those they engage. Other people, he stresses, are more than one-dimensional thinking beings; they have imaginations and emotions that play a vital role in making them receptive to the gospel story. —Simon Smart, executive director of the Centre for Public Christianity (Sydney, Australia)

(Read CT’s interview with Joshua D. Chatraw.)

Award of Merit

Why does God care who I sleep with?

Sam Allberry | The Good Book Company

I have read dozens of books on a biblical view of sexuality, and this one is excellent for a few reasons. First, it is honest. Sam Allberry shares his personal struggles with sexuality in an authentic fashion, and he doesn’t hide the challenges Christians face in making a biblical sexual ethic compelling today. Second, besides offering biblical answers, he explains the reasons why God gives particular commands. And third, he recognizes that the subject of sexual ethics touches on our ultimate desires, which can only be fulfilled through healthy relationships with God and other people. This is a relatively short book, but it is packed with insight. —Sean McDowell, associate professor of Christian apologetics, Biola University’s Talbot School of Theology

Biblical Studies

Reading with the Grain of Scripture

Richard B. Hays | Eerdmans

This volume, which features a collection of essays written throughout Richard B. Hays’s career, represents some of the New Testament scholar’s finest work. Like a masterful composer building a complex symphony, Hays artfully weaves together his writings, allowing the reader to hear recurring melodies that focus on Scripture as narrative, the unity of Scripture, reading Scripture within the community of faith, and the centrality of Jesus’ resurrection. Penetrating theological and exegetical insights permeate his work—nothing less is expected from such a seasoned and well-respected scholar. Ultimately, the book testifies to the complexity and coherence of the biblical story, sung by many voices but written by one author, God himself. —Carol Kaminski, professor of Old Testament, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary

Award of Merit

A Boundless God: The Spirit according to the Old Testament

Jack Levison | Baker Academic

Who knew that a word study could read like an adventure story—welcome to the world of the Holy Spirit in the Old Testament. As Jack Levison guides us through the various uses of the word in the Hebrew Scriptures, he offers insight into the refreshment, the surprise, the danger, and the boundlessness of the Spirit of God. Reading this book instantly enhanced my own appreciation for how the New Testament speaks of the Holy Spirit not in a vacuum but in continuity with the Old Testament witness. This is an exciting, illuminating read from beginning to end. —Peter Gosnell, professor of religion, Muskingum University

Children & Youth

Courageous World Changers: 50 True Stories of Daring Women of God

Shirley Raye Redmond | Harvest House Publishers

All parents know the power of influence and peer pressure. Why not let our kids be influenced by Christians whose lives show us what they believe? From around the globe and across the centuries, Shirley Raye Redmond selects 50 women who reveal what it means to live for God. The beautiful illustrations grab even the younger kids right away, but it’s the stories that have kept our family coming back again and again. These portraits of women who lived for God’s glory have opened my kids’ eyes to what God might do with their own lives. —Barbara Reaoch, former director of the children’s division of Bible Study Fellowship International

Award of Merit

Jesus and the Very Big Surprise: A True Story About Jesus, His Return, and How to Be Ready

Randall Goodgame | The Good Book Company

Told in a thoroughly engaging, personal way, Jesus and the Very Big Surprise focuses on the parable of the watchful servants (Luke 12:35–48). “He will dress himself to serve,” says Jesus of the returning master, and he “will have them recline at the table and will come and wait on them” (v. 37). What a beautiful truth to share so powerfully with little ones! The whimsical, engaging illustrations by Catalina Echeverri add to the delight of this wonderful picture book. —Glenys Nellist, author of the series Love Letters from God and Snuggle Time

Christian Living/Discipleship

Healing Racial Trauma: The Road to Resilience

Sheila Wise Rowe | InterVarsity Press

In this book, Sheila Wise Rowe provides a thorough examination of the nature and impact of racial trauma. Vividly, she helps us walk in the shoes of black people in America and understand the realities they face, but ultimately for the sake of pointing the way toward hope and healing. Her blend of biblical insights, personal stories, historical background, and cultural analysis makes for a helpful and timely read. It challenged me to embrace the influence of racial trauma upon my own life and to invite others to join me in both the pain and the healing. —Bryan Carter, senior pastor, Concord Church (Dallas)

Award of Merit

Created to Draw Near: Our Life as God’s Royal Priests

Edward T. Welch | Crossway

Many books are rich in doctrine but poor in application; many others attempt to build application on the shallowest of doctrinal foundations. Edward T. Welch’s Created to Draw Near weaves doctrine and life together in a unique and wonderful way. As we follow the Bible’s priestly theme, we see why our hearts burn for closeness, how Jesus draws us near, and what that means for our everyday mission in a fractured world. The result is a recovery of our status as God’s royal priests—an identity that really can transform our approach to God and neighbor. —Scott Hubbard, editor with desiringgod.org

The Church/Pastoral Leadership

A Place to Belong: Learning to Love the Local Church

Megan Hill | Crossway

The church is central to God’s redemptive work on earth. Yet we often struggle to see its beauty through the off-key singing, the clashing personalities, and the elements of its mission that are largely invisible. But as Megan Hill suggests, the church’s importance goes far beyond what we can see with our eyes. Her book encourages readers to rediscover the privilege of belonging to a local church fellowship, where we are cared for by elders and given opportunities to serve selflessly with our gifts. If you have grown disenchanted with the church, or you are looking to find your place within it, this book is for you. —Ernest Cleo Grant II, pastor of Epiphany Fellowship of Camden, New Jersey

Award of Merit

Diary of a Pastor’s Soul: The Holy Moments in a Life of Ministry

M. Craig Barnes | Brazos Press

M. Craig Barnes expresses the anguished beauty of the pastoral life with an exquisite intimacy that conveys the essence of going through life with a congregation. The fictional device he uses—journal entries from the diary of a pastor about to retire—works remarkably well. I recognized the sacred and the profane in every character he described. More than merely allowing others to peer over his shoulder voyeuristically, he teaches pastors to appreciate the divine image and the holy presence in average people and mundane moments. —Hershael York, dean of the School of Theology and professor of Christian preaching at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary

(Read CT’s review of Diary of a Pastor’s Soul.)

CT Women

Mother to Son: Letters to a Black Boy on Identity and Hope

Jasmine L. Holmes | InterVarsity Press

In Mother to Son, Jasmine L. Holmes opens her heart to her sons and her readers, exhorting us to better love and understand one another within the challenging social, political, and religious landscapes that we occupy. She calls us to be happily complex, nuanced, and tribal-less in our conversations around the most difficult aspects of living as salt and light in this fallen world. Her book inspired a set of longings in me—to read more broadly and deeply, to do better in conversations with those I disagree with, to live out the implications of the gospel with boldness and tenderness, and to write letters to my now-teenage son, helping him to unapologetically embrace the beauty and face the challenges that come with his ethnicity. —Kristie Anyabwile, writer and conference speaker, editor of His Testimonies, My Heritage

(Read CT’s review of Mother to Son.)

Award of Merit

Handle with Care: How Jesus Redeems the Power of Touch in Life and Ministry

Lore Ferguson Wilbert | B&H Publishing

I hadn’t given much thought to the importance of healthy touch until recently, when an older, single friend told me how many days she had gone without it during the pandemic. Lore Ferguson Wilbert’s book opened my eyes to the ministry of godly, healthy human touch. It helped me see how much of Christ’s work on this earth involved touching those to whom he ministered—and how necessary that touch was. We are embodied creatures, and touch plays a significant role in how we live out the calling to glorify God in our lives. Handle with Care is a timely guide that urges believers to follow after Christ in extending the ministry of touch to others. —Christina Fox, counselor and writer, author of A Holy Fear

(Read CT’s interview with Lore Ferguson Wilbert.)

Culture and the Arts

The Sound of Life’s Unspeakable Beauty

Martin Schleske | Eerdmans

I once heard the artist Makoto Fujimura say that when planting a church, a pastor’s first move should be inviting artists to play a central role. After reading The Sound of Life’s Unspeakable Beauty, I understand why. Martin Schleske is a writer, a violin maker, and—like all true artists—a lifelong learner. This unique book combines theology, philosophy, and personal stories of suffering and joy to emphasize the profoundly artistic nature of our individual and communal callings. It invites us to experience the sacred creativity of the gospel through the eyes of an attentive, ardent, and devoted artist and seeker. —Mary McCampbell, associate professor of humanities, Lee University

Award of Merit

Bezalel’s Body: The Death of God and the Birth of Art

Katie Kresser | Cascade Books

Who are we that creation yields its strange wonders, however fleetingly, to mere creatures? With beautiful prose and arresting images, art historian Katie Kresser explores the place and role of visual art in the history of the church and the wider Western world. Bezalel’s Body is at once a primer and an opportunity for novices and art lovers alike. Kresser sketches a distinctly cruciform history of art, emphasizing its implications for how we live with and love God and neighbor. We take a perverse pleasure in “seeing through” the artifice that overwhelms our culture; Kresser reminds readers that it’s possible to taste and see the truth—in all its otherness. —Matt Civico, blogger at Good Words, editor of Common Pursuits

Fiction

S. M. Hulse | Farrar, Straus and Giroux

This is a surprising and timely book, written with a compassion and tenderness rarely given to difficult topics like political tension within families and communities. In our polarized world, where reductionist thinking is largely the norm, S. M. Hulse’s novel offers us nuanced characters who are trying to sort out their complicated bonds to other people. It reminds us that no individual should ever be reduced to one moment, one action, or one belief. —Lanta Davis, associate professor of humanities and literature, Indiana Wesleyan University

Award of Merit

Thom Satterlee | Slant Books

Theodore Wesson is a young, ambitious, doubt-filled Anglican curate angling to leave his small country parish. In 1665, he meets a blind stranger named John Milton, who arrives in the village a refugee both from plague and political disfavor. (The great poet has yet to write his masterpiece, Paradise Lost, and much of England regards him as a traitor for his involvement in Oliver Cromwell’s republican revolution.) Milton’s support for the persecuted Quakers widens Wesson’s notions of God. But in time the friendship comes under strain when it threatens his clerical advancement. Is Wesson a reliable narrator? Maybe, maybe not. He is certainly guarded, and well aware of his own brokenness. But this is part of what makes God’s Liar so enchanting. In the end, this is a fine story about faith and doubt, providence and humanity, and the reality of encountering the living and active God. —Cynthia Beach, professor of English at Cornerstone University, author of The Surface of Water

History/Biography

Tornado God: American Religion and Violent Weather

Peter J. Thuesen | Oxford University Press

In this captivating study, Peter J. Thuesen assesses the mysteries of the tornado, its defiance of even the latest meteorological techniques for fully explaining it, and the sense of awe, terror, and reverence that it provokes. Tornadoes are often personified as evil beings that descend with little warning on defenseless populations, and for good reason. These devastating storms, which mostly appear in North America, cause catastrophic damage each year, leaving survivors to struggle with age-old questions of providence and theodicy. The tornado also provokes ethical questions, as many scientists attribute their rising frequency to climate change. Thuesen evaluates all these factors in a wide-ranging narrative that is delightful to read. —James Byrd, professor of American religious history, Vanderbilt University

(Read CT’s review of Tornado God.)

Award of Merit

They Knew They Were Pilgrims: Plymouth Colony and the Contest for American Liberty

John G. Turner | Yale University Press

John G. Turner is an extremely conscientious and broad-minded historian, and a lovely writer to boot. They Knew They Were Pilgrims should become the standard account of Plymouth Colony and its place in American religious history. The book skillfully pulls together a diverse range of sources to tell a nuanced story about the early New England settlers and their interactions with the Native Americans. Importantly, Turner does not neglect the often-marginalized voices of women, bringing to light figures like Awashonks, the female chief of a Rhode Island tribe who served, in the author’s words, as “a tenacious advocate for her people.” Readers will come away with a clear sense that the American concept of religious liberty is as diverse and complex as the people who first fashioned it. —Beth Allison Barr, associate professor of history, Baylor University

(Read CT’s review of They Knew They Were Pilgrims.)

Missions/Global Church

A Public Missiology: How Local Churches Witness to a Complex World

Gregg Okesson | Baker Academic

In our current era of pat answers and tweeted solutions to complex challenges, believers and local congregations need clear guidance on understanding their communities and being salt and light within them. A Public Missiology provides this abundantly. Drawing on a diverse set of cultural examples, Gregg Okesson walks readers through this process without losing sight of the critical role of individual conversion, thus defusing the most common critique against pastors and laypeople who want to influence their surrounding societies. This book inspired me, encouraged me, and supplied many moments of deep reflection. I highly recommend it to professors, college students, pastors, lay leaders, and a variety of ministry and NGO practitioners. —Mary Lederleitner, managing director of the Church Evangelism Institute, author of Women in God’s Mission

Award of Merit

A Multitude of All Peoples: Engaging Ancient Christianity’s Global Identity

Vince L. Bantu | IVP Academic

This is an important book! Its thesis is simple: Christianity has always been a global faith. Vince L. Bantu narrates a fascinating story of Christianity’s roots in places like Egypt, Ethiopia, Arabia, India, and China, a tale that is seldom told. In the process, he shatters the pervasive misperception of Christianity as a mainly white, Western, and often oppressive religion that was exported to the rest of the world. Carefully researched, the book describes vibrant ancient churches in the non-Western world with indigenous leadership and a contextualized theology, patterns that speak to the church’s identity and mission today. Bantu has rewritten the script for how we understand the character of global Christianity. I commend him for it! —Dean Flemming, professor of New Testament and missions, MidAmerica Nazarene University

(Read an excerpt from A Multitude of All Peoples.)

Politics and Public Life

Politics after Christendom: Political Theology in a Fractured World

David VanDrunen | Zondervan Academic

David VanDrunen provides a clear framework for Christians of all stripes to engage in the political process in diverse contexts. While those on either fringe of the political spectrum will find little comfort in its pages, the broad center will find intellectual resources not only for working out their own ideals but also for finding common ground with fellow citizens. Analyzing God’s covenant with Noah in Genesis 9, VanDrunen identifies this oft-overlooked passage not just as another story in the history of God’s interaction with humanity but as the basis for all public life. Politics, in his capacious understanding, stretches beyond mere statecraft to include economic and even familial relations. The book’s greatest strength is that it argues for political, social, and religious balance within the contours of Scripture. —Timothy D. Padgett, managing editor, The Colson Center

Award of Merit

Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States

Andrew L. Whitehead and Samuel L. Perry | Oxford University Press

Using extensive empirical analysis and insightful interview quotes, Andrew L. Whitehead and Samuel L. Perry provide the clearest picture yet of the beliefs and behaviors common to Christian nationalism, demonstrating how this movement co-opts the narrative and images of Christianity for political purposes. Their book explains both why Christian nationalists hold their views and how they differ from others who are religiously active. While readers may disagree with elements of the authors’ analysis, anyone who reads Taking America Back for God should agree that it fills a significant gap in our understanding of an influential slice of the American electorate. —Phillip Bethancourt, pastor of Central Church (College Station, Texas)

(Read CT’s analysis of three recent books on Christian nationalism.)

Spiritual Formation

The Deeply Formed Life: Five Transformative Values to Root Us in the Way of Jesus

Rich Villodas | WaterBrook

With the heart of a pastor, the mind of a scholar, and the voice of a friend, Rich Villodas offers a book for our time. All around us is evidence that Christians have, in Villodas’s words, been “formed by a shallow world.” The path to a deeper spirituality is an ancient path, but guiding people along it in the third decade of the 21st century requires surmounting the obstacles of our day. The Deeply Formed Life offers a rare combination of timeless truth and timely direction for restoring balance, focus, and meaning within our souls. —Richella Parham, author of A Spiritual Formation Primer and Mythical Me

(Read CT’s review of The Deeply Formed Life.)

Award of Merit (Tie)

The Way Up Is Down: Becoming Yourself by Forgetting Yourself

Marlena Graves | InterVarsity Press

The Way Up Is Down reflects on the importance of humility and self-emptying, drawing on personal stories and the example of Philippians 2:5–11, in which Paul exhorts us to imitate the servant mindset of Jesus. Marlena Graves has a winsome writing voice. She is funny, breezy, and casual. But the book has a hard-hitting, prophetic quality as well, as befits an author writing from outside the white, male mainstream. This book affected me. It made me feel uncomfortable (in a good way). People within my demographic (white males) would do well to read it. —Gerald Sittser, professor of theology at Whitworth University, author of Water from a Deep Well and A Grace Disguised

Soul Care in African American Practice

Barbara L. Peacock | InterVarsity Press

Barbara L. Peacock is a credible spiritual guide with deep evangelical convictions and a profound commitment to the African American community. Her book consists of short, engaging chapters, each one featuring an African American Christian whose life and ministry illustrate a theme she wishes to emphasize. Peacock’s writing bears the marks of someone who has read and studied deeply in the area of Christian spirituality. She continually invites readers to tend well to their own souls and to nurture their love for Christ. —James Wilhoit, professor emeritus of Christian formation and ministry, Wheaton College

Theology/Ethics

“He Descended to the Dead”: An Evangelical Theology of Holy Saturday

Matthew Y. Emerson | IVP Academic

Matthew Y. Emerson’s book studies a little-explored corner of Christology—namely, what happened during the time when Christ died and was laid in the tomb. Engaging a wide range of sources from every period of church history, he makes a persuasive case for recovering the doctrine of Christ’s descent. Many evangelicals wince at the phrase “he descended to hell” in the Apostles’ Creed because of its perceived connections to Roman Catholicism. But Emerson clears away misunderstandings that prevent us from identifying with the historic beliefs of the catholic (universal) church. He also highlights the pastoral encouragement offered in Christ’s descent: We need not face death alone, since Jesus has faced it—and conquered it—already. —J. V. Fesko, professor of systematic and historical theology, Reformed Theological Seminary

(Read CT’s interview with Matthew Y. Emerson.)

Award of Merit

The Holy Spirit (Theology for the People of God)

Gregg Allison and Andreas J. Köstenberger | B&H Academic

In this two-part introduction, Gregg Allison and Andreas J. Köstenberger draw upon their respective fields of systematic and biblical theology to provide a wide-ranging articulation of the doctrine of the Holy Spirit. Both sections offer not only a useful overview of Trinitarian controversies from the past but also faithful evangelical responses to their equivalents in our own day. While thorough, the book is never dry. Rather, the reader emerges with what the authors call a “theology filled with thanksgiving” for the Holy Spirit, who is both Love and Gift. —Elisabeth Rain Kincaid, assistant professor of ethics and moral theology, Nashotah House Theological Seminary

The Beautiful Orthodoxy Book of the Year

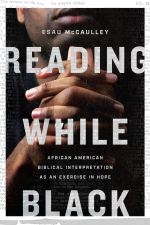

Reading While Black: African American Biblical Interpretation as an Exercise in Hope

Esau McCaulley | IVP Academic

This is an astonishing book I think every Christian should read—even those, like me, who do not live in the US. Esau McCaulley combines deep scholarship with an extraordinary ability to communicate with his readers, and his book brings the Bible back to the center of our consciousness on issues of race and discrimination. It is unapologetic in its resolute Christian voice and prophetic in the best sense of the word. From well-chosen quotes from black artists to troubling and at times amusing vignettes, the book feels like being given a fresh pair of glasses through which to reexamine a familiar story. Hopefully, it will launch a new kind of conversation around a highly fraught and difficult subject. —Sarah C. Williams, research professor in the history of Christianity at Regent College

In Reading While Black, McCaulley does a tremendous service to the church by putting black ecclesial interpretation into dialogue with the urgencies of our cultural moment, offering much-needed hope. This is the book I wish I’d had years ago as I wrestled to integrate my black-church rearing, my evangelical theological training, and my pastoral calling to cross-cultural ministry. At a time when increasing numbers of black people are questioning the legitimacy and relevance of Christianity to black concerns, McCaulley has insightful answers. He courageously addresses some of the most troubling issues for black folks with a scholar’s precision and a pastor’s heart. If you are a child of the black church, this book will remind you of home; if not, McCaulley hospitably throws open the doors so that you can come in, sit at our table, and be nourished by our testimony of what the Lord has done for us. —Russ Whitfield, lead pastor, Grace Mosaic church (Washington, DC)

This book is about hope. It is deeply theological, but also full of practical compassion and wisdom, made all the more compelling by McCaulley’s inclusion of bits and pieces of his own story. The way he flips abused biblical passages around, showing God’s heart for liberation, is both scholarly and beautiful. I believe this book will continue needed conversations within the church. I was humbled, challenged, and moved by it. —Rachel Joy Welcher, editor at Fathom magazine, author of Talking Back to Purity Culture

(Read CT’s September 2020 cover story, an adapted excerpt from Reading While Black, as well as an additional excerpt from the book.)

Award of Merit

Christ and Calamity: Grace and Gratitude in the Darkest Valley

Harold L. Senkbeil | Lexham Press

I loved this book. It is full of the unvarnished truth about the troubles of our fallen world, but it is neither abstract nor “teachy.” Rather, it drips with loving empathy and radiates a kind calmness as it reminds us that Christ is not absent from our suffering, but profoundly in it with us and for us. There is an unashamed liturgical dimension to Christ and Calamity, which makes it especially useful as a ministry resource. Already, I have recommended the book to a struggling believer who found it immensely helpful. Any Christian struggling with the trials and challenges of life will find it a great comfort and blessing. —Tim Patrick, principal of the Bible College of South Australia

At first, I couldn’t figure out why this book was in the running. As I read onward, the well got deeper and deeper. Although Christ and Calamity is plainly worded and borders on cliché at points, there is a genius to Harold L. Senkbeil’s use of garden-variety language that emerges only slowly. He doesn’t shrink from difficult passages of Scripture, but instead layers them in appropriately only after securing the trust of his audience with reassurance and comfort. Even in matters of death, Senkbeil refuses to give in to saccharine staples of heavenly relief; he simply instills the promises of Scripture—no more and no less—into the heart of the reader. The end result is truly beautiful. —Dru Johnson, associate professor of biblical and theological studies, The King’s College

This book is timely, given the realities of COVID-19, but it emphasizes that calamity visits us all on many different occasions and in many different guises. With short chapters, each focusing on one section of Scripture, in some ways it resembles a classic Puritan devotional. Christ is very much front and center. And hope is embedded in each chapter, but without it feeling like a magic wand to wave suffering away. This is a superb book that will pass the sniff test for anyone truly in pain. —Stephen McAlpine, lead pastor, Providence Church Midland (Western Australia)